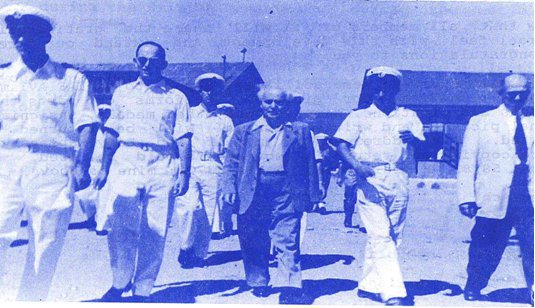

Left to right: David Ophir, Marvin Broder, David Ben-Gurion,

Samuel Yanai (Samech), David Hacohen

During World War II Marvin served in the U.S. Navy for five-and-a-half years in two destroyers in the North Atlantic, an escort carrier in the Pacific and for the last few months of the war he was shore-side on the staff of the Damage Control School in Philadelphia.

His initial involvement in Israel, apart from having a mother who was a Hadassah President, came in 1948 when he was asked to meet a representative of Land and Labor for Palestine, Wellesley Aron. Wellesley was a very British Empire-type who made aliyah in 1938. He joined up and became a major in the Jewish Brigade in the British Eighth Army. He told Marvin that Land & Labor was recruiting volunteers for military duty in Israel and was setting up a panel, a kind of admissions committee, to evaluate the competence and suitability of the various applicants. This group included about ten people with experience in infantry, artillery, and other military branches. Marvin and one other person were to be the naval interviewers.

These sessions were somewhat cloak-and-dagger, changing meeting locations frequently. Marvin always left these meetings with a feeling of guilt because he felt that on the basis of his experience and training, he had more to contribute than most of the people he was interviewing. This feeling was crystallized one night when Teddy Kollek sat in on the session. When the evening’s work was completed, Teddy said, “The fault with this meeting is that the guys who are asking the questions are the guys who should go.” That did it for Marvin.

He was engaged to be married then, and after the wedding the couple were on their way to Israel five days later, arriving in Haifa in March 1949. Marvin went up to the Stella Maris and reported for duty to Paul Shulman, a volunteer from the U.S.A. and first Commander of the Israeli Navy. The shooting war had stopped and Marvin’s job was to be in training. Apart from a small number of men who had some seafaring experience, he had to start from scratch. There were not even Hebrew words for nautical related terms. A fog nozzle became a “shpritzer,” two generators were “generatorim,” and perhaps to this day they are still called by these names.

The first schools were set up at Atlit, a radio operator’s course and a firefighting school. The staff of the firefighting course consisted of two young officers to whom Marvin spoke in English, two enlisted men from Morocco with whom Marvin spoke in French, while these four men would chatter away amongst themselves in Hebrew.

Several months after Marvin’s arrival to Israel, Paul Shulman retired and was succeeded in command by Shlomo Shamir, a high-ranking army officer. Shlomo’s emphasis was to be on training, not just boot training, but an attempt to standardize procedures and vocabulary and specific skills throughout all ranks. Shlomo summoned Marvin and asked him to accompany him through the former British Army camp at Bat Galim. This was where the Naval Training School was to be, and it still is there. Marvin became the first director of the school.

The visit was followed by a couple of hectic weeks of scraping, painting, plumbing and renovating and formulating a series of curricula, after which the school was ready to open. In 1949 the army had the benefit of approximately 30,000 men who had been trained by the British during the war. The Air Force had trained pilots, mostly volunteers from overseas. The Navy had only a few officers with British Merchant Marine papers, as well as some fisherman. The school was starting from rock-bottom.

The duration of the first course, designated Course Aleph, was to be nine weeks. The levels were: Captains and Executive Officers; Junior Deck Officers; Engineering Officers; Deck Ratings; Engineering Ratings; Radio Operators; Gunnery Ratings; Signalmen; and Cooks and Bakers.

Fortunately, an adequately qualified faculty was assembled with American and British Machalniks, supplemented by a few resident Merchant Marine sailors and a few instructors borrowed from the Technion. For military drill, several army people were on the staff, including David Ophir, Arye Kotic, and Shmuel Tankoos. Marvin was never able to bring himself to walk in British military style during parade formation; he claimed it made him feel like a dancer in the Sugar Plum King!

The graduation ceremony was attended by Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and Deputy Defense Minister David Hacohen, and was followed by lunch with the staff and graduates. Ben-Gurion asked Marvin, “Are they good sailors?” and he replied, “Not yet, sir, but they will be.” Ben-Gurion then said, “Ahad Ha’am said Jews would never become good farmers. He was wrong, we have become good farmers.” On reflection, Marvin believed that Ben-Gurion was right. Maybe at that time they were not yet good sailors, but as subsequent events proved, they became excellent sailors.

In 1993 Marvin and his wife were invited to visit the camp at Bat Galim. It was an extremely emotional moment for him. They were escorted by Admiral (res) Shlomo Erell, a graduate of Course Aleph, and met with the Commanding Officer Dror Aloni who held the position Marvin had once held. Marvin felt so proud to have planted the seed, helped by many others, for what had become a superior service academy and a most important facility dedicated to the continued well-being and security of the State of Israel and its people.

Source: American Veterans of Israel Newsletter April 1995, written by Marvin Broder