72ND INFANTRY BATTALION, 7TH BRIGADE

I.D. NO. 64636

The tumultuous years of World War II coincided with my high school years, and along with most students I dreamed of being able to participate in that war. Therefore, I must admit that there was a strong element of adventure in my decision to take part in the struggle to establish a Jewish homeland. In December 1944 I flunked my matriculation exam. I was sixteen-and-a-half, and the very next day I cycled to the recruiting office of Military Headquarters at the Union Grounds in Johannesburg. Displayed prominently on the wall was the sign “Join the Jocks and ride to victory on a tank.” The Transvaal Scottish Infantry Regiment was being formed anew as a tank unit. I saw two recruiting sergeants playing cards. Before I could tell them that I had come to sign up, they looked me up and down, and my ego plummeted as they said, “On your bicycle, chum, we’re not open for the school holidays.”

I went back to school for another year to try again. Early in 1946, compulsory part-time military service was renewed. I need not have enlisted, as I was Lithuanian-born and not yet a South African citizen. However, I volunteered and joined the Transvaal Scottish Infantry Regiment.

I did not belong to any Zionist youth movement, nor was I involved in any Zionist activities. Events in Palestine were far from my mind. My life was centered round my school and neighborhood friends and the regiment.

Events in Palestine during 1946/47 were not my first priority, until during the latter part of 1947, when I attended a compulsory regimental church service in full dress uniform. The sermon for that day at the Central Presbyterian Church just around the corner to the Union Grounds, equated British Mandate soldiers being attacked by Jewish patriots to the Roman legions facing the revolt of the Jewish zealots in the first century A.D. Something must have stirred in me, as I started to take a more serious interest in the events in Palestine, including the U.N. November 1947 Partition Resolution.

I knew that Jewish survivors in Europe needed a home, but the call in me to participate was still not awakened. I did not even know that a South African Zionist Federation existed, where I could have enlisted. Eventually, in February 1948, advertisements in the daily newspapers (inserted by the flamboyant Hebrew Legion) called for volunteers to join the fight for a Jewish state. Their meeting at a Berea communal hall on 22nd February 1948 was packed to capacity. I was one of those who signed on and started participating in week-end training sessions, together with the Betar movement, at the Rivonia Estate, about 10 miles from Johannesburg, belonging to Harry Elias Green; his Betarnik son, Hymie Green, was also to be one of the volunteers to join the 89th mechanized Commando Battalion of the I.D.F.

Ironically, the Hebrew Legion also conducted evening lectures at the Red Cross Hall opposite the Drill Hall, a stone’s throw from the Union Grounds. The A.C.F. (Active Citizens Force), in addition to evening lectures and parades at the Union Grounds, included an annual month of training at the Potchefstroom Military Camp. I had already attended the 1946 and 1947 camps and was a disciplined soldier, acquainted with all weapons required by the infantry in those days, which contributed to my selection for my eventual move to Israel.

In the months following February, I needed to obtain the official papers and an Italian visa. I was not yet 20, and the age of consent then was 21. As an alien in South Africa, I could not obtain a passport, only an “emergency travel document.” I also required parental consent for such papers. I wrote and signed my own letter, and was told about a Jewish barber in Main Street, opposite the C.I.D. offices, who was also a Commissioner of Oaths. When I approached him with my letter, he left his customer and turned to me, exclaiming in Yiddish: “Goot, goot du vorst zu Palestina” [Good, good you are going to Palestine], and without looking at the document, stamped and signed it with a flourish. My parents were not happy about it, but did not object.

In May 1948 I attended my third full-time training period. I was there when the State of Israel was declared, and also when the Nationalist party ousted Field Marshal Jan Smuts’ United Party in the 1948 South African parliamentary elections.

On completion of that training month, I returned to Johannesburg to find that the Hebrew Legion had disbanded, and some of its leaders had done a bunk. Well, what was I to do now? By then I knew about the Zionist Federation’s clandestine recruiting, and I went there to sign on. A high school friend and fellow worker at my first place of employment, who eventually joined our 72nd Battalion in Israel, Bernard Etzine, was on duty. Bernard warned me that because of my late application, my form would be at the bottom of the in-basket. However, some of my neighborhood friends were members of Betar; one of them, David Becker’s sister Shulamit was secretary of the Revisionist movement in Johannesburg, and he advised me to go and see her. I did so, and after a few weeks joined Raphael Kotlowitz’s large group of two planeloads of Betarniks, the largest group to fly north. Raphael had hired two planes from P.A.A.C, a Dakota and a converted wartime four-engine Halifax bomber, known as a Halton in its civilian version.

Most of the Johannesburg group flew up in the Dakota, and not being a regular member of the Betar, I did not know any of the Cape Town crowd in the Halton. Three of them joined the 72nd together with some Johannesburg fellows. Much later, in 2003 as editor of Henry Katzew’s book “South Africa’s 800,” I found out that Mendel Cohen, Mailech Kotlowitz and Hymie Berkman had served in Israel. Mendel had to have emergency appendix surgery in Rome, and Mailech and Hymie were left behind to care for him. I got to know the others during our voyage to Haifa on the ship “Dolores.” Mendel and I have remained good friends since those days.

Back to our flight north: like all the others, we left Palmietfontein airport in the early hours of the morning, with a refueling and breakfast stop in Bulawayo, Rhodesia. From there to Ndola, Northern Rhodesia, taking off again to our next night stop at Juba, Sudan, a long hop of about 1,200 miles, with another intermediate stop en route. Then we flew from Juba to Khartoum for another night stop. There we were met by Etzel representatives, who took us on a short tour of the city’s night life. On reading the local newspaper at the hotel, we saw a front-page photo and article about a parade of the Sudanese contingent, ready to leave to join the Egyptian forces in the Negev.

We started out early to fly to Wadi-Halfa, the most northern town of Sudan, on the Egyptian border, for refueling, The next stop was El Adem in Libya. We only stopped there for refueling and a meal, and we made the next flight to Rome during the night.

The Etzel ran two absorption camps in Italy, one in the north at Villa Forragiano on Lake Maggiore, and the other at the seaside resort of Ladispoli, west of Rome. Luckily we were sent to Ladispoli, spending a number of weeks there. The Etzel enclosure was situated opposite restaurants, a cinema and a dance hall, with a short walk down to the beach. The groups sent to Villa Forragiano were virtually isolated.

In mid-August we went by bus to Rome, and from there by goods train to Naples, where we boarded a small Greek ship, the “Dolores.” It had once been a private cruise yacht with accommodation for about 30 passengers. However, it now carried some 150 persons (no children), displaced Jewish refugees mostly from Romania, and included our Betar group of 21 men, 3 women and 3 Latin American volunteers.

Our flight from South Africa and our sea voyage were virtually uneventful. The sea was calm throughout the trip, and all the volunteers slept on stretchers on the open deck. One of our group, Dr. Alan Price, assisted by Evelyn Bernstein delivered a baby boy one day out of Haifa ¹.

We docked in Haifa on the morning of August 24th and were taken to the old Technion in Balfour Street for medical tests, and then to Tel Litwinsky, where we were given a few days leave. We left our luggage at the South African Zionist Federation offices. I looked up a boyhood friend of my father’s from our shtetl in Lithuania, and his 16-year-old son proved to be an excellent guide in the few days I spent in Tel Aviv.

Back at Tel Litwinsky, we were quickly sorted out, with 16 of our group ending up in the 7th Brigade, 8 in the 72nd Infantry Battalion and 8 in the 79th Armored Battalion, 6 in the airforce (including the 3 women) and one to the 89th Commando Battalion. Dr. Alan Price became a medical officer with the Givati Brigade.

Over the August/September period, the I.D.F. was strengthening the 7 th Brigade as an Anglo-Saxon unit which would operate using a common language. Our Brigade Commander was Canadian Machalnik, Ben Dunkelman. I cannot recall whether we disciplined Betarniks simply accepted the order to join the 7th, or whether we were influenced by the sales talk of various unit officers looking for recruits to join their outfits. I remember that during the short period at Tel Litwinsky, some Betarniks who had arrived earlier came to visit us, amongst them Louis Kotzen, an ex-classmate at Athlone High School and Eddy Magid whom I knew from Benoni, a town about 30km from Johannesburg, where I often spent my school holidays with my Katz relations. The third was Morrie Egdes whom I didn’t know. All three were members of the 82nd Tank Battalion, stationed at Lod Airport, not far from Tel Litwinsky.

On arrival at the 72nd Battalion camp at Samaria, near Nahariya , the other seven –Geoff Fisher, Hymie Josman, “Tookie” Levitt, Jack Marcusson, Archie Nankin, Albert Shorkend and Hymie Toker – opted to join our support company, and I chose the English-speaking Infantry “B” Company. I had been in the support company of my Transvaal Scottish 2 nd Battalion, qualified on 3″ mortars, signals and the use of Bren gun carriers, including driving them, and felt that there was more chance of action as a rifleman, and that was to happen about one week after joining the battalion.

I had once thought that I spent some weeks with the training platoon, but in 1998, having established per an official passenger list that we had arrived in Haifa on 24th August 1948, it seems that I was wrong. I now estimate that we arrived at “Samaria” on 30th August 1948. At the time “B” Company had two under-strength platoons which had already completed 10 days of training. I joined what was then known as the training platoon, commanded by Stanley Medicks, who had been a captain in the Kings African Rifles. The others in my training section and occupying the same tent were two others from Kenya, Ian Walters and Jack Banin, and South Africans Mike Snipper from Germiston, Colin Marik of Johannesburg, Max Krensky of Cape Town, and a few British chaps.

In the 72nd we had an abundance of officers and N.C.O.s with World War II experience as instructors. Some of the names that come to mind are Derek Bowden (U.K.), Stanley Medicks (Kenya), Jeff Perlman (South Africa), David Susman (South Africa), Jack Franses (U.K.), Jack Branston (U.K.), Julie Lewis (Canada) and Len Fine (Canada).

The training in the week before the Tamra clash of September 7th/8th was quite intensive, as it was in the weeks afterwards, in between other skirmishes, night patrols and operations.

On September 6 th preparations were on the go for our first test. All of us in Medicks’ training platoon were posted to the other two platoons. I ended up in Number 1 platoon’s second section commanded by Cliff Epstein (U.K.). The second-in-command and the one in charge of the Spandau light machine gun group was Canadian Hymie Klein. The gunner on the Spandau was Canadian Alec (Pee-Wee) Dworkin, and his assistant was Canadian “Alter” Leff. Other Canadians were Hank Meyerowitz, Howard Cossman and Jack Belkin, and Belgian Benjamin Hirshberg, and I; I think Joe Korenstein from the U.K. and an Indian from Bombay, Ezra Mekmal, whom everyone called “Ghandi,” were also with us.

As much as I try, I cannot remember my feelings preparing for this action – fear or excitement? – I simply cannot recall, but it has been written about in other Machalniks’ stories. I cannot even remember the bus trip to get to the village. After disembarking in early evening of 7th September, I do remember the platoon getting in line formation and going up the hill, under cover of mortar fire of our ‘sister’ 71st Battalion. As we got closer to the top, we were ordered to fire in volleys from the hip. I still remember our platoon commander, a sabra, Aharoni Landman, shouting in his accent, “straighten de line or I kill you all.” I supposed he meant “straighten the line or you will all be killed.” But years later, when we were already living in Israel, when I reminded him of that sentence, he insisted that he meant what he had said!

We reached the crest of Kabul Mountain without opposition, and spread out. As first light broke, the Arabs started their counterattack with well-placed Bren light machine guns which raked our positions. As a result of my peace-time experience in the use of the Bren, I could recognize the slower rate, as compared to the fast-firing Spandaus we were using. Having no entrenching tools, my partner Benjamin Hirschberg and I had dug shallow slit trenches in the difficult rocky terrain, using a scout’s sheath knife I had, and our British steel helmets. Our section of ten men had been positioned on the extreme right of the company, relatively safe from the intense counterattack fire of the enemy. We were taking casualties, when suddenly our platoon sergeant, South African David Susman appeared, ignoring the fire, and called on me to assist in the evacuation of a badly wounded man who had been hit in the back. No stretchers were available at the top of the mountain. Four men had to carry him, stomach downwards. Only then did I have to face the fierce hail of fire and ricocheting bullets flying all over. I don’t remember how far we carried wounded British medic Max Schmuelowitz. Did we have a first-aid post on the mountain, or did we carry him all the way down to the village of Tamra?

On returning to my section, which had withdrawn behind a stone wall of a now roofless hut, I learned that my partner Hirshberg had been killed. A burst of Bren fire had gone right through the wall and torn his armpit off. On reflection, if I had not been called out to help, I could have very well been hit by the same burst. Eventually it was discovered that the enemy had managed to surround us on three sides. At this stage our Platoon Commander, Aharoni Landman, called me to rush to find the second Platoon Commander, Zachariah Feldman, and ask him to attack the Arab force from the left, before they could completely surround us. Being a good soldier, off I went with bullets whining and whistling around me. After covering about 100 yards, I realized that I did not really know which way to go, so I rushed back to Landman, who immediately set off on his own, after advising Feldman and Jeff Perlman that our sergeant David Susman had been wounded. This really angered Perlman, and what followed was the famous wild charge led by him and Feldman with about half of their platoon, who were positioned close by. This forced the enemy off the peak and we remained in control. In this clash South African medic Locky Fainman was cited for bravery, treating the wounded under heavy fire, and all those involved thought that South African Sergeants Perlman and Susman had distinguished themselves for leadership and coolness, as well as inspiring their men under fire.

Somehow, and I do not know why, perhaps because I was closest to the officer involved, I was dispatched to help to move Hirshberg’s body to the rear (I think it was with Benny Landau and Gordon Mandelzweig). On my return, once again my squad had moved to another position. At this stage, in the late afternoon, Company Commander Schutzman appeared, and I reported to him. He suggested I reinforce the number two platoon, which had suffered the most casualties. I ended the engagement spending the night in the positions of Harry Eisner’s squad, which had been the main group in the previously mentioned charge. This action caused us to lose the lives of three men, Benny Hirschberg (a Belgian), Sydney Leizer (a Canadian) and Polish-born British volunteer Shlomo Bornstein. In addition to David Susman and Shmuelowitz, some ten others had been wounded, and in the course of my research over the years, I have established at least some of their names: Harry Blackman (U.K.), Mickey Olfman (Canada), Max Wolf (U.S.A.), Dick Feuerman (U.S.A.), Colin Marik (S.A.), and Arne Bodd (Norway).

For our English-speaking “B” Company, this firefight was the toughest we had experienced. In other war histories it would just be considered a “skirmish.” In fact the rest of our service, including “Operation Hiram,” was just a series of skirmishes. Unlike my South African friends in the 89th Commandos and the 4th Troop anti-tank guns, we never ever experienced heavy artillery or even mortar barrages, but this was enough for this lad seeking a bit of adventure. Once you see what can happen to men getting hit, your attitude changes and it becomes a matter of doing your best and getting the job done.

Back at camp, Cliff Epstein, our section commander, was relieved to see me. He was worried that something might have happened to me. After our return, I spent a few days leave in Tel Aviv, together with the Americans of Eisner’s group. We became life-long friends. Eisner died in 2001, two weeks before his 89th birthday, and I am still in contact with Issy Cohen’s widow, Elaine. Eisner was in his late 30s, with World War II experience. He was not the only volunteer in that age group: another was Canadian member of my squad, Hank Meyerowitz. He could hardly see, and how he got into our infantry unit no one knew, but he was a great morale booster. During the firefight on the mountain top, he would stand up with bullets whizzing all over shouting, “A Yid ken geharget veren do.” [A Jew can get killed around here!] That helped to reduce the fear and tension, as he was like a character straight out of a Damon Runyon story. He used to write a daily newsletter called the “Gazoz Gazette.” When we were in camp it was stuck on the company notice board, and when we were in the field he would write about daily happenings on toilet paper, and our platoon runners, either Ezra Mekmal from Bombay or Joe Korenstein, a 17-year-old Holocaust survivor from the U.K. would have to take the news to all our platoon’s positions, even under sniper fire. Meyerowitz found in “B” Company a South African cousin, Jack Mirwis. Their mothers were sisters and had lost touch before World War I.

I’d like to write some more about Hank Meyerowitz’s role as a morale booster. Later on, in the winter months (December ’48 and January ’49), when we were in the lines opposite the Syrians at Kibbutz Mishmar Hayarden, the entrance to his dug-out had a sign: “Everyone welcome – bring your own cigarettes.” South African Solly Bental was in our platoon, and he used to gamble on the horse races in Cape Town. Each platoon had a donkey or two to bring up supplies from the main road to their positions. One of the signs read “Damascus Donkey Derby – see Bental for best prices.” He affectionately called one of the donkeys “Basil,” after our second-in-command, Basil Sherman, who used to ride over to inspect our positions on a horse borrowed from Kibbutz Machanayim, where our company headquarters was situated. A day or two before Christmas 1948, Hank was on an inter-platoon patrol with British Jonathan Balter. They were fired upon by the Syrians and dropped to the ground in the dark. Balter lost touch with Meyerowitz, but got back safely. Hank was missing for about 24-hours. He had lost his glasses and couldn’t see, but luckily managed to crawl back in our direction and was found by a friendly Bedouin. We had spent many hours of daylight sending out search parties for him. Sometimes he would approach me and say, “Gee, you’re looking well, Joe, when are they gonna bury you?” Or he would approach Harry Klass, who had a large nose, and say to him, “Give me a light, Harry – oh, sorry, I thought you were smoking a cigar.”

The first elections in Israel took place on 25th January 1949. We were really not interested in voting. I personally could not vote, as in November, when identity photographs were taken, I had still not returned to camp after an extra day’s leave taken A.W.O.L. About a week before the elections, I had been on a two-day leave to Tel Aviv, when I went to visit Shulamit Becker, who had accepted me into the Betar.

She was working at Menachem Begin’s Herut election office. She introduced me to Mr. Begin, and when I left she asked me to take Herut election pamphlets to hand out to the guys. I gave them to Hank, and the next morning they appeared all over our position – they were in every dug-out, every machine gun post, every ammunition box, and so on. The brigade education and welfare officer heard about this, and the next day Mapai (Labor) propaganda appeared everywhere. It was in fact an interesting election if you happened to be in a town or city. Every party had its election slogans and speeches prepared in about a dozen languages.

When I visited Hank in Winnipeg in 1952, he was running an illegal gambling house, with a dry cleaning and shoe repair depot as a front. He had a fox terrier called Joe in my honor, but I had a feeling that the dog’s name was changed often, depending on his current visitor.

Our next move was on 11th September 1948 to the Birwa area (today Moshav Ahihud) where our company headquarters were situated. No. 2 Platoon occupied positions on the south side of the Akko-Safed road, and our No. 1 Platoon held the Camel Mountain peak on the north side.

My squad’s light machine gun group, together with a P.I.A.T. anti-tank group, were dug in on the road at the bottom of the heights where Jeff Perlman, now our platoon sergeant, was in command. Lieutenant Landman was in charge of the group on the peak.

Shortly after settling down, Epstein, our squad commander, developed cave fever, and was hospitalized. Normally his second-in-command Hymie Klein would have taken over, but he was at the bottom of the mountain, so I was given the responsibility of commanding the remainder of our squad on the peak. The week was spent guarding and observing the enemy on the next, higher mountain. Except for occasional sniper fire, the week was uneventful.

On the 18th September we were suddenly replaced by a regional defense unit and returned to camp. There were rumors that Count Folke Bernadotte, the United Nations mediator, had been assassinated by one of our extremist groups. Don’t remember how long we had to get organized, but after a meal and a change of clothing, we set off on a five-hour journey to Safed via Nazareth and Tiberias, where for the first time we saw the beautiful blue waters of the Kinneret.

After a short break in Tiberias, we carried on to Safed, passing verdant kibbutzim along the way, and then continued along the winding road past Rosh Pina and into the old city of Safed. We had a meal, and then assembly, when our company C.O., Captain Schutzman, made a short speech. “Well, men, this is what you came here for, D-Day, when fighting will begin all over Palestine. “A” Company will attack Meron and our “B” Company is assigned to capture twin-peaked Mount Meron.” We called it “two-tit” mountain. This first attempt to carry out “Operation Hiram” was postponed because of Bernadotte’s murder, as were all other planned military operations.

Our company bivouacked in an Arab cemetery, settling down with our blankets between the tombstones. One morning of those few days we spent there, some fellows of the No.2 Platoon heard some digging sounds amongst the graves, though I did not hear it. Apparently, one of the guys had heard that Moslems are buried with their valuables, and wanted to dig some of it up. After these few days in the graveyard, we moved to more permanent quarters. Our platoon took over a small unused hotel, and from there we undertook patrols and occupied mountain positions overnight.

Our No. 2 Platoon had a harrowing experience during a two-section patrol on the approach to Meron, when our own forces of the 79th fired at them. The hotel where we were quartered had been badly damaged in the early fighting in May, so we built showers out of oil drums on raised platforms in the yard. Harry Klass, an electrician by trade, repaired the electrical wiring which provided us with light. It was not all patrols and hill-holding – we were taken out by bus to visit the Lake Hula area, and later for a two-day break at a beach on the Kinneret. There were no girl clerks in our 72nd Battalion, and one evening around a campfire I performed an African war dance in the nude. It was witnessed by women soldiers from our brigade headquarters. We were also visited by a group of South Africans from Kibbutz Ma’ayan Baruch who had heard about the dozen or so South Africans at Safed. When we weren’t out on patrol or sitting in night positions on some hill, we were free in the evenings to get acquainted with the locals of Safed, drinking beer in little cafés, and even providing them with some entertainment by imitating African war dances.

For us foot soldiers all good things came to an end, so after making ourselves comfortable we were returned to our base camp near Nahariya, this time returning via the beautiful Jezreel valley. Perhaps these trips to and from Safed, influenced me to settle in the Lower Galilee when I brought my family on aliyah in January 1969.

From our base, we carried on with more intensive training, forced marches and active mountain night patrols, sometimes with evening passes to Haifa or Nahariya. On 15th October, we were ordered to prepare for action again and the entire 7th Brigade was on the move.

We were taken by bus to a point just past Nahariya and then came a real test of stamina and endurance in a grueling four-and-a-half hour march at a fast pace with full equipment, through valleys and hills to reach Kibbutz Eilon at 00.30 hours. Cliff Epstein had returned from his hospitalization, but now commanded No. 1 section of our platoon. Our section leader was Hymie Klein, and I was his second-in-command in charge of our Spandau machine gun crew. My number one on the Spandau was Alec Dworkin, a short fellow called Pee-Wee who had to carry the heavy Spandau. I helped him for a while but his gun was eventually taken over by Simon Novikow, a powerful fellow of No. 3 Section who carried both his Spandau and Pee-Wee’s. At the kibbutz we bedded down in the open in an adjoining forest to prevent observation by Kaukji’s forces, the reason for this long night march.

In the morning, we were told not to leave the forest and were briefed that all our forces in the country were to be on the move. In another try at “Operation Hiram,” the 7th would move from the west. In order to clear the hills overlooking the road, our platoon and No. 2 Platoon had to capture the Arab village of Ikrit. We were supported by the new English speaking “D” Company, only one platoon, commanded by David Appel. Our “A” Company was assigned to the capture of Tarshiha (Ma’alot today), southeast of us, and then an armored column of the 79th would fight its way to Sasa. Then “B” and “D” Companies would be picked up to support the 79 th. At 18.30 we were assembled to move when Captain Schutzman came and told us that due to our successes in the Negev, and for political reasons, our “Operation Hiram” was again postponed

On 18th October we marched back a few kilometers, were met by buses and taken back to base at Samaria for another few days of intensive training until the next fighting patrol on 22nd/23rd October. Meanwhile, a small rebellion was brewing in the ranks of our No. 2 Platoon and on the 21st October, ten or eleven of the men staged a sit-down strike outside the company headquarters office, and they were put into the camp lock-up. I believe that it was all started by two or three of them who could not take the discipline and the many tough mountain patrols and marches, and persuaded others to join them. I was told by a reliable witness that two of them swam out to a ship in Haifa Bay intending to stow away and get to Europe, but the ship’s captain had them returned to the military police. I do not remember if all ten of them were returned home, but I do know that six of them were. One of the rebels had complained that the army was being taken over by a lot of Johnny-come-lately’s who had begun to transform our volunteer unit into a bunch of silly saluting “barracks monkeys”. What nonsense – our “B” Company had lost three men killed before the strike, and five saluting “barracks monkeys” afterwards. “We had fought well,” he said.

So why did he not stay and finish the job?

That same afternoon we were ordered to get our full battle gear ready again. That evening I was corporal of the guard at the camp lockup. Coming from the large mess and recreation hall, were the sounds of a piano beating out South African folk liedjies [songs]. I said to the rebels, “Don’t try any tricks, I’m going to sit with my friends for a while.” Gerry Davimes of Johannesburg was thumping away at the piano, while the South Africans stood around. I happened to look up and saw the expression on Lou Hack’s face – he was far away, nostalgic, in South Africa and not in Israel. (This was the same piano on which a week earlier, the well-known Pnina Saltzman had given a recital for the 72nd Battalion at Samaria.)

I had not known Hack personally in Johannesburg; he was 5 years older than myself, but we all lived in the same Jewish suburb of Doornfontein. I remember as a young lad going into his mother’s corner fruit and vegetable store to buy a small paper bag of monkey nuts – unshelled peanuts – as we called them in those days

On 22nd October we were taken by bus to Kibbutz Eilon to make a lightning raid on Kaukji’s headquarters at Ikrit. About half-way there, No. 2 Platoon would remain as a covering force and No.1 Platoon would cut across the hills to the village, and as it was during a cease-fire period, it was essential to return to our lines before daylight.

Our Platoon Commander now was Stanley Medicks from Kenya. He was a fearless leader in the tradition of “follow me,” and Jeff Perlman was our platoon sergeant, as our regular O.C., Lieutenant Landman, had been hospitalized with a stomach bug. Eventually Captain Schutzman saw that we wouldn’t make it in the required time. I was close enough to hear him on the walkie- talkie radio asking for instructions. We spread out across a hill and for about 15 minutes opened up heavy fire with every weapon we had – Spandaus and rifle fire – in the direction of Ikrit, still some distance away.

I made myself comfortable, sitting on a rock directing the fire of our Spandau group. We then started our return march, plodding wearily, but as fast as we could through enemy territory, each of us immersed in his own thoughts. We were already back on the road, and before we reached the cover of our no. 2 Platoon, we suddenly heard the whirring sound of a spent bullet above us. We heard Simon Novikov shout for a medic. Lou Hack had been hit. Our medic “Locky” Fainman applied a dressing and a morphine injection, but we had no stretchers with us. “Locky” organized a stretcher by using two rifles slung through the sleeves of battle dress jackets. We carried on, quickening the pace, anxious to get Lou to Kibbutz Eilon for proper medical attention. Waiting at the kibbutz was our South African medical officer, Harry Bank, and an ambulance driven by South African Simon Stern. We still had a considerable distance to go. Without changing pace we all took turns at carrying the stretcher. We finally reached the kibbutz and the ambulance took Lou to hospital in Nahariya. It was impossible to tell where this stray bullet came from in the winding mountain roads. We could be facing in one direction for a while, and then in another direction; it could even have come from our side. We were bussed back to camp, and on waking next morning, we were shocked to hear that Lou had died on the way to hospital.

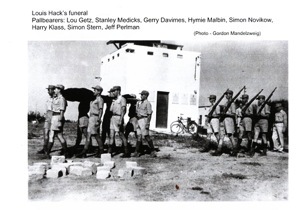

Later that day, October 23rd, Lou was buried in a military funeral at the Nahariya cemetery; all the pallbearers were South African. In the firing party were Ian Walters (Kenya), Cliff Epstein (UK), Hymie Klein (Canada) and Jack Franses (UK).

Louis Hack’s funeral. Pallbearers: Lou Getz, Stanley Medicks, Gerry Davimes, Hymie,Malbin, Simon Novikow, Harry Klass, Simon Stern, Jeff Perlman

Photograph reproduced with the kind permission of Gordon Mandelzweig

Lou Getz, a personal friend of Louis Hack, had been brought over from the 79th Battalion for the funeral. Getz’s parents, like the Hacks, also ran a fruit and vegetable shop two corners further up Beit Street, opposite the Talmud Torah hall, synagogue and cheder [Hebrew School].

On the 26th we were again on the move. “Operation Hiram” was on, but after passing Akko we halted and returned to camp. Apparently, the air force was not ready. The next day, the 27th, we set off as planned, traveling eastwards through the Jezreel valley and then northwards towards Safed. This time we did not stop at Tiberias but raced silently through it in the failing light.

As our bus was quite full at Samaria, Tex Paschkoff (U.S.A.) and I boarded one of the trucks, loaded with medical and hospital equipment, including stretchers. We opened up two of them, lay down and slept comfortably for a good portion of the drive. Suddenly we were awakened by a violent stop and excitement. On the difficult winding road from Tiberias to Rosh Pina, driving without lights, the bus carrying the Besa heavy machine gun platoon left the road and turned over. Luckily there were no serious injuries. However, South African Geoff Fisher was taken to the hospital in Tiberias for observation. Tex and I had jumped off the truck in case help was needed. A little while later, a truck carrying mortar shells and other ammunition also capsized. Because of these delays the journey took a few hours longer than anticipated.

The morning of October 28th found us once again in Safed. Resting during the day, we were on our way that evening. This time “B” Company was to liberate Meron with “D,” the other English-speaking company in support. Then other forces of the 7th would bypass us, and carry on towards Jish (Gush Halav). The 9th Brigade, which included a number of platoons of Latin American Machalniks, supported by three armored cars of the 79th, was to attack from the west, capture Tarshiha and join us at Sasa.

Before setting off that evening, we spent half-an-hour watching our air force bombing our objectives. I think I recognized at least one Dakota amongst them. Bursts of ack-ack fire could be seen exploding around our aircraft. We set off from Safed in our buses, singing loudly, until we were a few kilometers from an opening to descend into Nachal Amud (the Pillar Stream, so named because of a lone isolated rock sticking up like a pillar). Having toured this valley during our years in Israel, as an accompanying parent guard in daylight, I wonder if we would have refused and rebelled had we known where we were being led into. It reminded me of old Tarzan movies, the African porters carrying their heavy packs over narrow paths with a sheer drop on the side leading into the chasm, but I suppose being young and stupid we would have obeyed orders and carried on.

We silently set off in single file along the course of Nachal Amud, following the Haganah guide, with the intention of attacking Meron from the rear. We walked and stumbled for hours. Suddenly a burst of machine gun fire was directed at us. It wounded Jack Banin, a bullet hitting him just below the right nostril and exiting at the back of his neck. Our medic Fainman was there immediately to dress the wound. Jack, an observant Egyptian-born Kenyan, thought he was finished and recited the “Hear oh Israel” prayer. He did recover, but suffered some facial paralysis. Naturally, we had all hit the dirt, and lay in that cold valley for an unnecessary length of time, while our company C.O. was making up his mind to move on.

I understand that David Appel C.O. of “D” Company, which was supporting us, came forward and got our C.O. to get moving, but a considerable amount of time had been lost, which delayed our assault. We eventually reached our attack positions while our mortar support came crashing down, the shells exploding quite close to us and hitting the village above. Before daylight set in, Lieutenant Feldman’s No. 2 Platoon attacked from the right flank and our platoon spread out, giving support by exchanging fire with the enemy, shooting from the windows of what seemed like a large fortress.

While we were so engaged, Feldman and his sergeant, Jack Franses, led their platoon into the building, clearing it room by room. It was, we learned later, the tomb of Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, one of the leaders of the revolt against the Romans in A.D. 135. Our platoon commander Stanley Medicks ordered me to rush to the end of the building with my L.M.G. group of Pee-Wee Dworkin and Joe (Palmach) Korenstein, as well as an additional soldier from another section, my old friend Bernard Etzine, to cover and prevent any enemy defenders from escaping.

We had just got into position when someone did try to escape and he was cut down by our fire. He was so close we could not miss. I did however hold back our fire temporarily to determine for sure that it was not one of our 2nd Platoon comrades coming out. Shortly afterwards, we were in possession of the tomb and we proceeded to clear the now empty village house by house. We met no resistance, just isolated fire from a hill opposite us. Except for one soldier killed, our casualties were light, but Jack Banin was seriously wounded, South African George Schlachter was hit in the leg, and South African Lionel Clingman and Canadian sniper Jack Belkin attached to No. 2 Platoon were hit by rock splinters. The dead volunteer, a relatively recent arrival, was Viennese-born Shmuel (Fritz) Daks, who arrived in the U.K. with the kindertransport during the month before World War II broke out on 1st September 1939.

While clearing the village, I noticed what seemed to be a large bomb crater in the center of it, and pondered at the accuracy of our air force. This had a sequel during my leave after the operation, when at the South African Zionist Federation office I met Sammy Tucker, a navigator on one of the aircraft giving us support. He was from the town of Benoni, a contemporary of my cousin with whom I often spent my school holidays. I congratulated Sammy on the accuracy of their firing. His reply was, “You’re crazy, our target was Tarshiha,” about 20 kilometers to the west.

At Meron, part of the captured arms were some German Mauser rifles, a superior version of the Czech-manufactured ones we had. I took one and handed mine in to our stores truck, but I forgot to check and adjust the sights, which probably cost me another hit later on in the hills around Sasa.

After a late breakfast, we climbed back on our buses and headed for Jish (Gush Halav), passing Sifsufa, both of which had been captured by our 79th Armored Battalion supported by our own 72nd “A” Company. At Jish, the supply truck caught up with us and we were given sandwiches and hot drinks. We rested for a while and at about 2 p.m. we were on the move again, by foot this time. First in single file, and as we got away from Jish we left the road and spread out in open formation through sparse olive groves. At this stage some light artillery or mortar fire was directed at us as we advanced to clear the groves and the hills around Sasa, our next target.

During these moves, someone had brought mail from the South African Zionist Federation, and I think I was one of the recipients of a letter from home; later, when we stopped to rest while isolated shells were still landing, we sat down to read our mail. Whilst lying and dozing in the field someone shouted, “Look!” We jumped to our feet, and to our delight saw all the vehicles of the 79th and some of Golani, armored or otherwise, making their way along the winding road in the direction of Sasa. We climbed up a hill and dug in for any possible enemy counterattack. At 11 p.m. we were suddenly moved down to the road to board waiting halftrack armored vehicles.

Louis Hack’s funeral. Pallbearers:Lou Getz, Stanley Medicks, Gerry Davimes, Hymie,Malbin, Simon Novikow, Harry Klass, Simon Stern, Jeff Perlman

Photograph reproduced with the kind permission of Gordon Mandelzweig

Lou Getz, a personal friend of Louis Hack, had been brought over from the 79th Battalion for the funeral. Getz’s parents, like the Hacks, also ran a fruit and vegetable shop two corners further up Beit Street, opposite the Talmud Torah hall, synagogue and cheder [Hebrew School].

On the 26th we were again on the move. “Operation Hiram” was on, but after passing Akko we halted and returned to camp. Apparently, the air force was not ready. The next day, the 27th, we set off as planned, traveling eastwards through the Jezreel valley and then northwards towards Safed. This time we did not stop at Tiberias but raced silently through it in the failing light.

As our bus was quite full at Samaria, Tex Paschkoff (U.S.A.) and I boarded one of the trucks, loaded with medical and hospital equipment, including stretchers. We opened up two of them, lay down and slept comfortably for a good portion of the drive. Suddenly we were awakened by a violent stop and excitement. On the difficult winding road from Tiberias to Rosh Pina, driving without lights, the bus carrying the Besa heavy machine gun platoon left the road and turned over. Luckily there were no serious injuries. However, South African Geoff Fisher was taken to the hospital in Tiberias for observation. Tex and I had jumped off the truck in case help was needed. A little while later, a truck carrying mortar shells and other ammunition also capsized. Because of these delays the journey took a few hours longer than anticipated.

The morning of October 28th found us once again in Safed. Resting during the day, we were on our way that evening. This time “B” Company was to liberate Meron with “D,” the other English-speaking company in support. Then other forces of the 7th would bypass us, and carry on towards Jish (Gush Halav). The 9th Brigade, which included a number of platoons of Latin American Machalniks, supported by three armored cars of the 79th, was to attack from the west, capture Tarshiha and join us at Sasa.

Before setting off that evening, we spent half-an-hour watching our air force bombing our objectives. I think I recognized at least one Dakota amongst them. Bursts of ack-ack fire could be seen exploding around our aircraft. We set off from Safed in our buses, singing loudly, until we were a few kilometers from an opening to descend into Nachal Amud (the Pillar Stream, so named because of a lone isolated rock sticking up like a pillar). Having toured this valley during our years in Israel, as an accompanying parent guard in daylight, I wonder if we would have refused and rebelled had we known where we were being led into. It reminded me of old Tarzan movies, the African porters carrying their heavy packs over narrow paths with a sheer drop on the side leading into the chasm, but I suppose being young and stupid we would have obeyed orders and carried on.

We silently set off in single file along the course of Nachal Amud, following the Haganah guide, with the intention of attacking Meron from the rear. We walked and stumbled for hours. Suddenly a burst of machine gun fire was directed at us. It wounded Jack Banin, a bullet hitting him just below the right nostril and exiting at the back of his neck. Our medic Fainman was there immediately to dress the wound. Jack, an observant Egyptian-born Kenyan, thought he was finished and recited the “Hear oh Israel” prayer. He did recover, but suffered some facial paralysis. Naturally, we had all hit the dirt, and lay in that cold valley for an unnecessary length of time, while our company C.O. was making up his mind to move on.

I understand that David Appel C.O. of “D” Company, which was supporting us, came forward and got our C.O. to get moving, but a considerable amount of time had been lost, which delayed our assault. We eventually reached our attack positions while our mortar support came crashing down, the shells exploding quite close to us and hitting the village above. Before daylight set in, Lieutenant Feldman’s No. 2 Platoon attacked from the right flank and our platoon spread out, giving support by exchanging fire with the enemy, shooting from the windows of what seemed like a large fortress.

While we were so engaged, Feldman and his sergeant, Jack Franses, led their platoon into the building, clearing it room by room. It was, we learned later, the tomb of Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, one of the leaders of the revolt against the Romans in A.D. 135. Our platoon commander Stanley Medicks ordered me to rush to the end of the building with my L.M.G. group of Pee-Wee Dworkin and Joe (Palmach) Korenstein, as well as an additional soldier from another section, my old friend Bernard Etzine, to cover and prevent any enemy defenders from escaping.

We had just got into position when someone did try to escape and he was cut down by our fire. He was so close we could not miss. I did however hold back our fire temporarily to determine for sure that it was not one of our 2nd Platoon comrades coming out. Shortly afterwards, we were in possession of the tomb and we proceeded to clear the now empty village house by house. We met no resistance, just isolated fire from a hill opposite us. Except for one soldier killed, our casualties were light, but Jack Banin was seriously wounded, South African George Schlachter was hit in the leg, and South African Lionel Clingman and Canadian sniper Jack Belkin attached to No. 2 Platoon were hit by rock splinters. The dead volunteer, a relatively recent arrival, was Viennese-born Shmuel (Fritz) Daks, who arrived in the U.K. with the kindertransport during the month before World War II broke out on 1st September 1939.

While clearing the village, I noticed what seemed to be a large bomb crater in the center of it, and pondered at the accuracy of our air force. This had a sequel during my leave after the operation, when at the South African Zionist Federation office I met Sammy Tucker, a navigator on one of the aircraft giving us support. He was from the town of Benoni, a contemporary of my cousin with whom I often spent my school holidays. I congratulated Sammy on the accuracy of their firing. His reply was, “You’re crazy, our target was Tarshiha,” about 20 kilometers to the west.

At Meron, part of the captured arms were some German Mauser rifles, a superior version of the Czech-manufactured ones we had. I took one and handed mine in to our stores truck, but I forgot to check and adjust the sights, which probably cost me another hit later on in the hills around Sasa.

After a late breakfast, we climbed back on our buses and headed for Jish (Gush Halav), passing Sifsufa, both of which had been captured by our 79th Armored Battalion supported by our own 72nd “A” Company. At Jish, the supply truck caught up with us and we were given sandwiches and hot drinks. We rested for a while and at about 2 p.m. we were on the move again, by foot this time. First in single file, and as we got away from Jish we left the road and spread out in open formation through sparse olive groves. At this stage some light artillery or mortar fire was directed at us as we advanced to clear the groves and the hills around Sasa, our next target.

During these moves, someone had brought mail from the South African Zionist Federation, and I think I was one of the recipients of a letter from home; later, when we stopped to rest while isolated shells were still landing, we sat down to read our mail. Whilst lying and dozing in the field someone shouted, “Look!” We jumped to our feet, and to our delight saw all the vehicles of the 79th and some of Golani, armored or otherwise, making their way along the winding road in the direction of Sasa. We climbed up a hill and dug in for any possible enemy counterattack. At 11 p.m. we were suddenly moved down to the road to board waiting halftrack armored vehicles.