I returned to South Africa towards the end of January 1946 after having served in the Tank Corps in World War II, and was demobilized on 25th February, 1946.

I returned to South Africa towards the end of January 1946 after having served in the Tank Corps in World War II, and was demobilized on 25th February, 1946.

I decided to study law at university, and as I was an ex-serviceman, my tuition and a living allowance were given to me and others like me by the government and the Governor General’s War Fund, an organization formed to assist ex-servicemen. In April 1948, in my third year at university, there was a call to young Jews, especially those who had served in World War II, experienced soldiers and airmen, to go to Israel which was about to become independent. Volunteers were needed to join the Haganah in the fight against the Arabs, who threatened to overrun Israel as soon as the British left, towards the middle of May 1948. South African Jews who had served in the South African Air Force in World War II had already begun leaving for Israel to help form an air force — in fact, some had flown planes purchased by South African Jewry to Israel. A group of us at university decided to volunteer at the beginning of May 1948.

I was scheduled to fly out of South Africa with the Friday night group, but as I had been chosen to play in the inter-varsity first team rugby on the Saturday, and I really wanted to play in the game, I arranged to leave on the Monday. I must say that my mother did not object to my joining the Israeli army.

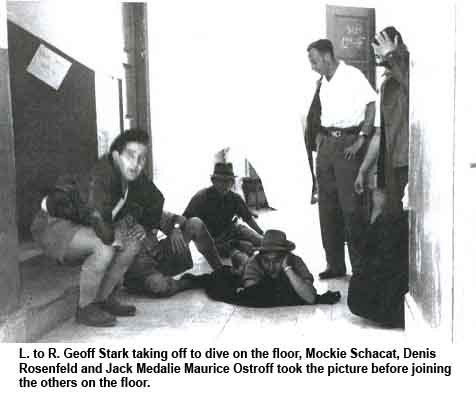

Israel received its independence on the 15th May, 1948. It was around about then that we flew from Johannesburg to Rome, where we stayed overnight and met the group which had left on the Friday night before us, and we then flew from Rome to Haifa. The British Army was still in Israel, and in charge of customs and immigration.  I remember that while we were being registered and sorted out (it was chaotic as usual), there was an air raid alarm and some bombing, but not at the airport. Somebody still has a picture of me dropping to the ground as soon as we heard the bombing, and others following suit when we realized how close the bomb was.

I remember that while we were being registered and sorted out (it was chaotic as usual), there was an air raid alarm and some bombing, but not at the airport. Somebody still has a picture of me dropping to the ground as soon as we heard the bombing, and others following suit when we realized how close the bomb was.

We were taken by truck to Sarafand, not far from Tel Aviv. This was the main British army base during the occupation of Palestine. The Israelis suffered from a lack of arms and military equipment. I was issued with a .303 rifle and a limited amount of ammunition, which was in short supply. The thought of going into action this way was terrifying, but the Israelis had one weapon which the Arabs did not have and which eventually proved a winner: courage and dedication and a will to fight for their lives. The Arabs, other than the Jordanians who had been trained by the British and were commanded by a British general known as Glubb Pasha, did not want to fight. You must remember that the ordinary Arab soldier was a conscript who was treated by his officers like a dog — the officers had the luxuries while the ordinary soldiers had nothing.

After the first few days at the base camp, where we were trying to find out what was to happen to us, a young chap joined us. He must have been 18 or 19 years of age (although I was only 22 years old, I had spent over three years in the army and had seen action and been wounded twice, so I was a seasoned soldier). He seemed too young to be able to hold a command rank; I still remember his name, it was Meshulam. He said he was from the First Gedud of the Palmach and wanted to know if any of the South Africans wanted to join his unit. He spoke rather a good English; he was a sabra and he has a head of thick black hair with a boyish, good-looking face — I can still picture it. None of the South Africans wanted to join the Palmach, which was a type of commando unit. Most of the South Africans with me, those who had fought in World War II, had not served in the infantry. They had either served in the air force, artillery or navy. I was sick and tired of sitting around waiting to be allocated to a unit (apart from the air force, which was put together by South Africans assisted by a few Americans, the Israeli High Command did not know what to do with the volunteers from South Africa), so I agreed to go with him. There was also a young chap from Russia (I spoke to him in Yiddish which he understood) and he decided to come with me. We took our clothes and climbed into the Israeli’s jeep and off we went to his camp, which I remember was near a place called Tel Litwinsky. In any event, we did not have to travel far.

When we arrived at the camp, there was a flap on. At the time, there was not an actual war being fought, but there were various skirmishes. The Arabs were waiting for the British to leave Israel before launching a full-scale war. In the meantime, world Jewry and Jewish supporters were spending millions of dollars to buy arms and military equipment for the Haganah to defend Israel.

The British, during their mandate, and in order to police Palestine, had built a series of fortress-like police stations overlooking the main roads between cities. They were impregnable, except to shelling from tanks or artillery. The British handed over these police stations to the Arabs when they left. One of the police stations was called Latrun, and it overlooked the main road between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. It was handed over and occupied by the Jordanian army. Of all the armies lined up against Israel, the Jordanians were the most formidable. However, the Jordanian army was not that big, and as far as I can recall, it did not get involved in the fighting as much as Egypt, Syria, Iraq and the other Arab countries. It limited itself to the central areas, in particular the area around Jerusalem.

At the time of Independence, East Jerusalem was under the control of Jordan, and West Jerusalem was under Israeli control. Because Latrun overlooked the main Tel Aviv-Jerusalem road, as well as the position of West Jerusalem geographically, the Jordanians were able to blockade it. In order to circumvent the blockade of the main road, Israel built a new dirt road to West Jerusalem. The Palmach unit I joined was guarding the Burma Road, as it was called. Shortly after Independence, the Arabs began their full-scale attack on Israel. It was thus necessary to ensure that West Jerusalem should not fall to the Jordanians and to achieve this, my unit had to protect the convoys using the Burma Road; it was also targeted by Jordanian artillery and therefore Israel was forced to send more and more convoys by night. This method was dangerous because the trucks could not travel with lights full on, and the road they were traveling was not tarred and was surrounded by rock overhangs. We used to ride on the back of the trucks to prevent ambushes. Fortunately, the Arabs did not like to operate at night.

When we were not guarding the Burma Road, we went back to base which was not too far away. Apart from fighting a war with the Arabs, the Israeli government under Ben-Gurion had to contend with internal problems, namely organizations which had fought the British during their rule of Palestine before Independence, such as the Irgun controlled by Begin. There was also another organization called the Stern Gang. These organizations had their own private armies who were not prepared to accept the authority of Ben-Gurion and the Haganah. There were rumors that the Irgun was bringing a huge load of arms and ammunitions from Europe, together with the immigrants who were their supporters, on a ship called the “Altalena”. On the 20th June, the Palmach received orders to surround the beachfront of Tel Aviv and to use force to prevent the Irgun from off-loading the arms and ammunition. Apparently the Irgun intended beaching the “Altalena” on the Tel Aviv shore, removing the arms and ammunition with the help of the immigrants on the ship. We took up positions all along the beachfront. I remember that I had a position alongside a hotel which I frequented when on leave in Tel Aviv. Although we had been ordered to open fire on the people trying to off-load the ship, I don’t think that I and the other members of the Palmach would have done that. Fortunately, we were not called upon to do so. The ship was forced to drop anchor some distance away from the beach, and the Irgun did not attempt to off-load. The passengers disembarked onto small boats and the ship was abandoned with the arms and ammunition still on it. We withdrew from our positions and returned to our base camp. The arms and ammunition were later removed by the Haganah and the ship was left to rot where it had dropped anchor. I remember that while I was on leave in Tel Aviv later in the year, people often swam out to the wreck.

Shortly thereafter, due to international pressure, a truce of two to three weeks was declared. Notwithstanding the truce, there were still skirmishes, and both sides were busy replenishing their arms and equipment. There had previously been attempts by the Haganah to capture Latrun without success, as these attempts were made without the assistance of artillery. Latrun and the other police stations taken over by the Arabs were surrounded by rolls of barbed wire. The Haganah had to use a weapon to cut a path through the barbed wire. It was called a bangalore torpedo. This instrument was a long light steel rod or pipe with dynamite attached to one end. There was some trigger arrangement at the other end to set off the dynamite when it was applied to the barbed wire, which was torn apart by the explosion. As there were a number of barbed wire fences, this operation had to be repeated several times. Once a path had been cut, the soldiers had then to breach the huge gates at the entrance to the police station. The previous attacks on Latrun had taken place at night, when ostensibly everyone was sleeping. In order to succeed, the barbed wire fences had to be pierced before the soldiers inside the police station woke up. In each of the previous attacks, the fences had not been pierced quickly enough; therefore, the soldiers in the police station received enough warning to enable them to get to their posts to fire on the Haganah from the top of the police station, and some attacks had to be abandoned with loss of lives.

Israel had formed a tank unit, with tanks and armored vehicles stolen or purchased from the British before they left. This tank unit was under the command of a South African, Clive Selby. He had been an officer in the British Army. The Palmach, under the command of Yitzhak Sadeh, decided that as soon as the truce ended, there would be a further attack on Latrun, but this time with a tank and some armored cars. The attack was to be carried out by my Palmach unit. The truce ended on 19th July. In the early morning of that day, we assembled on a small hill overlooking the main road to Latrun, about two miles away. The convoy was to be led by a Cromwell tank, and following the tank were buses carrying our Palmach fighters; interspersed between the buses were some armored vehicles. After being addressed by Yitzhak Sadeh, we set off down the main road, with hooters blowing and the troops singing. It must have been an imposing sight, and possibly frightening to the soldiers in the police station. I was in the first bus, which was the third or fourth vehicle behind the Cromwell. We were not traveling nose to tail, but my bus was not too far behind the tank. I imagined that as soon as the tank got closer to the police station it would open fire on the police station with 75-mm armor-piercing shells, powerful enough to breach the gates and walls of the police station and destroy some of the barbed wire fences. The buses would pass the tank and the Palmach men would jump out and commence the attack and any barbed wire fences barring the way would be destroyed by the bangalore torpedoes. Well, it did not happen that way. At the entrance to the police station the tank had not opened fire as expected, it veered to the left and started returning to our jump-off point with all the other vehicles following suit. The attack appeared to have been aborted without a shot having been fired. I was never able to find out why the attack was aborted. Whatever the reason, I was pleased, as the type of attack we had proposed launching was very dangerous and would have led to a lot of casualties. We then returned to our base camp.

Editor’s note: Here’s what actually happened:

A British sergeant, a deserter known as Tex was in command of the Cromwell. A Jordanian gunner had almost scored a direct hit on the tank. Tex ordered the tank gunner to knock the gun out. The tank gunner replied that he could not, as his the gun had jammed and required an extractor tool to remove the shell casing. There was only one such tool in the whole brigade and it was with Rutledge in the other Cromwell at Lydda. Tex saw that the enemy soldiers were withdrawing from the fortress and all that was needed was for the Israelis to drive in and take over. He ran to the lead vehicle and ordered them to go in. Apparently the driver did not understand English, and thought he had been told to fetch the tool. When he arrived at Lydda he was appalled to see that the whole convoy had followed him. A great opportunity was lost, as all operations were to stop at 5.45 p.m. according to the U.N. truce conditions.

After the aborted attack on Latrun, we were ordered to secure the hills surrounding Ramle, near Lod (Lydda) Airport, which was still occupied by Arabs. The intention was that as soon as we had cleared the hills around Ramla, an attack was to be launched against Ramle and Lydda, also occupied by Arabs. This was not difficult, as we did not find too many villages occupied — the Arabs had left when they saw us advancing. We made sure the villages were empty by conducting a house-to-house search. The hills we occupied had a clear view of the terrain between Ramle and Lydda. That night, 12th July, the attack began. There was little resistance from the occupiers. I don’t know the size of the Arab population occupying these two towns, but I recall a figure of 40,000. In any event, the next morning a delegation from the Arabs who had left came to our commander to ask for safe passage through the hills. He agreed and gave the delegation an escort back to the other refugees. The Arabs did not take prisoners of war, but there were occasions when our soldiers were captured by Egyptians and treated as prisoners of war. It happened to a very good friend of mine, Monty Goldberg, who had come to Israel with me. He was an aerial photographer, and after a photographic mission on 14th August over the Gulf of Aquaba, the Fairchild aircraft’s engine faltered and the pilot, Paltiel Makleff, had to make a forced landing in the Negev. After a few days of harrowing treatment at the hands of Bedouin, they were taken prisoners of war by the Egyptians.

The Egyptians controlled the area of the Gaza Strip. Israel controlled the Negev, but in order to get into the Negev you had to travel in sight of the Egyptians. The Egyptians occupied the police stations and fortresses built by the British to control any uprising by Arabs in Palestine at the time of the British occupation. It was therefore dangerous to cross into the Negev during the day and you only did so at night. Sometime in August or September 1948, the Palmach was ordered to relieve the IDF in the Negev. We crossed over one night as we passed some units of the IDF moving out into Israel proper. I came across some friends of mine who had come to Israel with me, and they told me what they had been doing and what we would be doing: they patrolled the Negev in jeeps mounted with machine guns.

I was stationed at a small kibbutz called Shoval, while our headquarters was at Kibbutz Ruhama. I remained in the Negev for about three months. During this period there was another truce, which enabled us to replenish our arms and ammunition and other equipment. Our function in the Negev was to get rid of unfriendly Arabs. There were some friendly Arabs — like the Druze — some of whom fought alongside the Israelis. One of these battles was a night attack on a police station near Negba. For the attack, we were joined by new immigrants who had been drafted into the IDF. Unfortunately, they had received very little training and the attack on Negba was their first experience of war. I had long forgotten the cover a soldier in World War II had received from support groups before launching an infantry attack, but I never lost the fear that each attack would be my last.

I was in command of a section of ten soldiers of new immigrants. With me was another South African, Harold Hassall, who had joined us a few days earlier. He was also an experienced World War II soldier. We advanced towards the police station. In front of us were some engineers who blew a path through the barbed wire. The enemy in the police station began firing on us. I told my section to open fire, which they did, but I suddenly realized that they were not firing at the police station but into the ground in front of us. They were so frightened by the Arab fire that they closed their eyes and pointed their rifles downwards and fired into the ground in front of them. Afterwards, Harold told me that the men alongside him were doing the same, but the seasoned Palmach fighters did not lose their heads and were returning fire effectively. Unfortunately, the new recruits started retreating and it then became obvious that the attack had failed. One of our sergeants had been wounded and was left behind. I ran up to him and lifted him onto my shoulder and starting carrying him back to where our transport was. In the dark, I did not know where I was going. You must bear in mind that we were guided up to the police station by sabras who knew the terrain — I did not know how to get to the police station — all I knew was that we had moved up a hill through ravines. Some way down the hill, Harold bumped into me — he had seen what I had done and was looking for me so he could help me carry the wounded soldier down to the transport. Between the two of us, we managed to get him down the hill and handed him over to the medics. The next day, there was a post-mortem about what had happened: the lesson that we learned was that you can’t use untrained troops in such important actions.

On one occasion I was asked to accompany a sergeant to visit a so-called friendly Arab village in the Negev. It turned out that they were not so friendly and we were lucky to escape with our lives. The lesson I learned then was not to trust my fellow soldiers’ views on whether an Arab was friendly or not. As far as I was concerned, no Arab was friendly.

Whilst in the Negev, I participated in an attack against another police station called Iraq-el-Suweidan which was occupied by Egyptians. This was a night attack as well and we had the assistance of two dive bombers, one flown by a South African from Potchefstroom, Danny Rosen, and the other by a non-Jewish Canadian, Len Fitchett; Len’s plane was shot down and all the crew killed. We did not succeed in reaching the gates of the police station, and we pulled back with a few casualties. The bombing had the effect of making the Egyptian soldiers keep their heads down, hence there were relatively few casualties on our side.

The last big attack I was involved in was the capture of Beersheba in the central portion of the Negev. This attack took place on 21st October. Again it was a night attack. The function of the Jeep Commando, as we were known, was to go in first with guns blazing, to be followed by the infantry in buses and trucks. Beersheba was not a big city at that time. To this day, I don’t know whether it was occupied by Arab troops and if so, how many. Our orders were quite clear: the Jeep Commando had to go in shooting, making as much noise as possible. We were to encircle the city, firing all the time, thus giving the impression of a large force, and once we had exhausted our ammunition, we were to pull back and let the infantry go in and mop up. I must tell you that it was like a fireworks display. There were three of us on the jeep. There were also two machine guns rigged up on it. One was in front, the other was in the rear. I drove, one of my friends manned the front machine gun and the other manned the rear machine gun. In addition, we had grenades and submachine guns. Well, it went off as planned. I don’t remember how many times we circled the city, but it was quite a few. We lobbed grenades and I fired one of the submachine guns while driving. We then got the order to pull back, which we did and watched the infantry go in with lights on full and hooters blaring. We did not stay for long, as we were ordered back to base. The next day we heard that the attack had been successful and that Beersheba was ours. I don’t know how many casualties there were, but my group did not suffer any. Thereafter, I don’t recall how many more operations my unit was involved in, but we were moved out of the Negev and back to the main base camp near Tel Aviv. On all fronts Israel had done well and the Arabs were on the retreat. Therefore, when the outside world pressured for a cessation of hostilities, the Arabs were more than agreeable, and a final truce was arranged for some time in January, I think. In any event, when I got back to our main base camp and took some leave in Tel-Aviv, I met the friends with whom I had come to Israel and a number of us decided to return to South Africa to resume our studies. I think I got back to South Africa at the beginning of February, just in time to register.

My wife has reminded me that when she met Harold Hassall in South Africa, after we were married, he told her that I saved his life in Israel. He had been wounded and I had carried him to safety. As far as I can recall, this took place in one of the attacks against a police station. I did not mention it before as it had slipped my mind. I did not want to appear as if I spent my time rescuing fellow soldiers.

CATEGORY: PERSONAL STORY

GEOFF STARK

PALMACH – YIFTACH

I returned to

I decided to study law at university, and as I was an ex-serviceman, my tuition and a living allowance were given to me and others like me by the government and the Governor General’s War Fund, an organization formed to assist ex-servicemen. In April 1948, in my third year at university, there was a call to young Jews, especially those who had served in World War II, experienced soldiers and airmen, to go to Israel which was about to become independent. Volunteers were needed to join the Haganah in the fight against the Arabs, who threatened to overrun

I was scheduled to fly out of

We were taken by truck to Sarafand, not far from Tel Aviv. This was the main British army base during the occupation of

After the first few days at the base camp, where we were trying to find out what was to happen to us, a young chap joined us. He must have been 18 or 19 years of age (although I was only 22 years old, I had spent over three years in the army and had seen action and been wounded twice, so I was a seasoned soldier). He seemed too young to be able to hold a command rank; I still remember his name, it was Meshulam. He said he was from the First Gedud of the Palmach and wanted to know if any of the South Africans wanted to join his unit. He spoke rather a good English; he was a sabra and he has a head of thick black hair with a boyish, good-looking face — I can still picture it. None of the South Africans wanted to join the Palmach, which was a type of commando unit. Most of the South Africans with me, those who had fought in World War II, had not served in the infantry. They had either served in the air force, artillery or navy. I was sick and tired of sitting around waiting to be allocated to a unit (apart from the air force, which was put together by South Africans assisted by a few Americans, the Israeli High Command did not know what to do with the volunteers from South Africa), so I agreed to go with him. There was also a young chap from

When we arrived at the camp, there was a flap on. At the time, there was not an actual war being fought, but there were various skirmishes. The Arabs were waiting for the British to leave

The British, during their mandate, and in order to police

At the time of

When we were not guarding the

Shortly thereafter, due to international pressure, a truce of two to three weeks was declared. Notwithstanding the truce, there were still skirmishes, and both sides were busy replenishing their arms and equipment. There had previously been attempts by the Haganah to capture Latrun without success, as these attempts were made without the assistance of artillery. Latrun and the other police stations taken over by the Arabs were surrounded by rolls of barbed wire. The Haganah had to use a weapon to cut a path through the barbed wire. It was called a bangalore torpedo. This instrument was a long light steel rod or pipe with dynamite attached to one end. There was some trigger arrangement at the other end to set off the dynamite when it was applied to the barbed wire, which was torn apart by the explosion. As there were a number of barbed wire fences, this operation had to be repeated several times. Once a path had been cut, the soldiers had then to breach the huge gates at the entrance to the police station. The previous attacks on Latrun had taken place at night, when ostensibly everyone was sleeping. In order to succeed, the barbed wire fences had to be pierced before the soldiers inside the police station woke up. In each of the previous attacks, the fences had not been pierced quickly enough; therefore, the soldiers in the police station received enough warning to enable them to get to their posts to fire on the Haganah from the top of the police station, and some attacks had to be abandoned with loss of lives.

Editor’s note: Here’s what actually happened:

A British sergeant, a deserter known as

After the aborted attack on Latrun, we were ordered to secure the hills surrounding Ramle, near Lod (Lydda) Airport, which was still occupied by Arabs. The intention was that as soon as we had cleared the hills around Ramla, an attack was to be launched against Ramle and Lydda, also occupied by Arabs. This was not difficult, as we did not find too many villages occupied — the Arabs had left when they saw us advancing. We made sure the villages were empty by conducting a house-to-house search. The hills we occupied had a clear view of the terrain between Ramle and Lydda. That night, 12th July, the attack began. There was little resistance from the occupiers. I don’t know the size of the Arab population occupying these two towns, but I recall a figure of 40,000. In any event, the next morning a delegation from the Arabs who had left came to our commander to ask for safe passage through the hills. He agreed and gave the delegation an escort back to the other refugees. The Arabs did not take prisoners of war, but there were occasions when our soldiers were captured by Egyptians and treated as prisoners of war. It happened to a very good friend of mine, Monty Goldberg, who had come to

The Egyptians controlled the area of the Gaza Strip.

I was stationed at a small kibbutz called Shoval, while our headquarters was at Kibbutz Ruhama. I remained in the

I was in command of a section of ten soldiers of new immigrants. With me was another South African, Harold Hassall, who had joined us a few days earlier. He was also an experienced World War II soldier. We advanced towards the police station. In front of us were some engineers who blew a path through the barbed wire. The enemy in the police station began firing on us. I told my section to open fire, which they did, but I suddenly realized that they were not firing at the police station but into the ground in front of us. They were so frightened by the Arab fire that they closed their eyes and pointed their rifles downwards and fired into the ground in front of them. Afterwards, Harold told me that the men alongside him were doing the same, but the seasoned Palmach fighters did not lose their heads and were returning fire effectively. Unfortunately, the new recruits started retreating and it then became obvious that the attack had failed. One of our sergeants had been wounded and was left behind. I ran up to him and lifted him onto my shoulder and starting carrying him back to where our transport was. In the dark, I did not know where I was going. You must bear in mind that we were guided up to the police station by sabras who knew the terrain — I did not know how to get to the police station — all I knew was that we had moved up a hill through ravines. Some way down the hill, Harold bumped into me — he had seen what I had done and was looking for me so he could help me carry the wounded soldier down to the transport. Between the two of us, we managed to get him down the hill and handed him over to the medics. The next day, there was a post-mortem about what had happened: the lesson that we learned was that you can’t use untrained troops in such important actions.

On one occasion I was asked to accompany a sergeant to visit a so-called friendly Arab village in the

Whilst in the

The last big attack I was involved in was the capture of

My wife has reminded me that when she met Harold Hassall in

Machal/geoffstarkjoe24909finaljoe410909