Aaron was drafted into World War II as an Army medic, then became an Air Force pilot flying P-47s over the China hump.

In the spring of 1948, Aaron was working as a salesman of radio components. One night in early May, he was woken up by a stranger sitting on his bed. He assumed his roommate let the man in, but had no idea who the guy was. The stranger tried to convince Aaron to fly for the Jews in Palestine and asked what it would take. Red’s thinking was that any Jews willing to stand up and fight for their lives deserved all the help he could give them, and that he would do it for a bottle of whisky, cigarettes and $30 a month.

Only days later, Red flew to Rome on a TWA Constellation, unknowingly sitting next to future comrade-in-arms Syd Antin.

Red and Syd finished their S-199 training at Ceske Budejovice in early June and hitched a ride on a LAPSA C-46 leaving flying from Zatec to Israel with a planned stopover in Ajaccio, Corsica

An iced-up carburetor forced the C-46 to set down early at an Italian airbase at Treviso, in northern Italy. The base commander had previously proven friendly to Israeli aircraft crews and he had not bothered searching their planes for contraband cargo. Again, the base commander took the LAPSA captain’s word that they were flying civilian cargo to the Americas – but when he left the area, one Italian soldier took his own initiative and peeked into the fuselage, where he saw Finkel and some crates. The soldier pointed a gun at Finkel and demanded that he open the boxes.

Finkel, thinking quickly, refused to do any such thing until the base commander returned, and used the interim to collect potentially incriminating documents in the cockpit. Among the papers, Finkel found an envelope addressed to the 101 Squadron Commander from Dr. Otto Felix, the Israeli contact in Czechoslovakia who met many arriving 101 recruits in Prague. The letter read: “Aaron Finkel. Typical American. Oversexed. To be watched.”

When the Italian commander and Regional Chief of Police returned, they insisted that Finkel open a crate. The aircrew and passengers tried to convince the Italian authorities that the crates carried surveying equipment.

“Now, anybody who has ever seen an ammunition box knows what the hell is in it. So they had a pretty good idea when they saw the ammunition boxes. The machine guns were in much longer boxes and they were in two layers. Even though we told them it was surveying equipment, they insisted on opening up the box. When they took the cover off, the top layer had the tripod for the machine gun, and I think the sight of something else in there. But the guts of the machine gun were not in the top layer. When they saw the tripod, we tried to say, “See, that’s for the surveying equipment.” Understand too, the language difficulty. It was tricky. Then the guy motions, “Open up the rest of it,” and we did. Of course there was that ugly air-cooled barrel – you couldn’t call that surveying equipment. It was pretty obvious what it was. They thought we were running guns for communists somewhere. It’s what they were worried about, and that’s why they grabbed onto us and locked us up until they found out differently.” (Syd Antin)

The Italians decided to take crew and passengers into custody. Red asked to make a phone call which they allowed, and he called Danny Agronsky (publicly the local LAPA official, but secretly in charge of the Haganah’s European air operations). The group was then hustled towards the base’s jail. Finkel, Antin, and Don Kosteff (the C-46 pilot) shouted indignantly that they were Americans and could not be treated in this fashion, upon which they were asked if they wanted to see the U.S. Consul. Since the U.S. had maintained an arms embargo against the Middle East and any American citizen serving in the armed forces of another country could lose his citizenship, all three quickly declined. Agronsky secured their release but not before they had spent three nights in jail.

Upon release the group took a steamboat from Treviso to Venice in order to catch a flight to Haifa on a Jewish-owned South African airline arranged by Agronsky.

Once Stan Andrews and Bob Vickman had designed the red and black angel of death logo for the 101 Squadron, the squadron decided it needed an identity, a calling card. Finkel wrote to his sister in New York and asked her to send him a package of red baseball caps.

Once they arrived, the squadron became known as the Red Squadron and its red caps became a mark of distinction on nights out in Tel Aviv.

Finkel was quick to aid his fellows in danger. When British Machalnik Cyril Horowitz crashed an S-199 on 1st August, Finkel drove a jeep to the wreck and jumped out, pulling him free of the wreck, risking the danger of the wreck exploding.

Finkel took part in Velvetta 2, flying with Jack Cohen.

On 2nd January 1949 Finkel and Sy Feldman took two Spitfires from Hatzor to attack rail traffic in Sinai.

“We carried out a very successful ground attack on a troop train, just west of El Arish. After strafing with cannon and machine-gun fire, we then bombed a railway junction. We returned a little early since Red’s Spitfire was starting to overheat” (Sy Feldman).

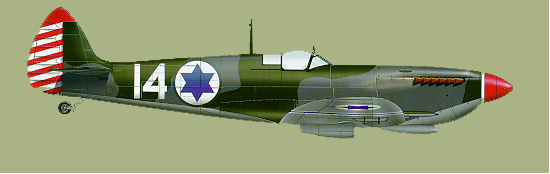

Two days later, Finkel destroyed a Spitfire. Finkel, in a White 14, took off accompanied by White 12 for a late afternoon reconnaissance of Rafah. The pilots spotted and reported ten small vehicles on the Rafah-Gaza road and about 85 more heading southeast from Rafah to Al Auja. On landing at Hatzor, Finkel’s Spitfire blew a tire. The plane skidded off the end of the runway and flipped on its back. Whilst the plane was a mess, Finkel escaped, shaken but unhurt. That was his last combat sortie.

After the war, Finkel stayed on long enough to help the 101 Squadron move to Ramat David air base and then returned to the U.S.A.

Source: Machal West Newsletter: Summer 2006, and 101 Squadron website – www.101squadron.com