Laurence Kohlberg published this article in the Autumn 1948 issue of the Menorah Journal after having served on the “Paducah,” renamed “Geula” [Redemption]) after graduating from Phillips Academy in Massachusetts towards the end of World War II. He enlisted in the service and was assigned as a second engineer on a transport ship. This is a testimony written almost immediately after the experience. It is the report of a very bright twenty-year-old.

We were the eighth or ninth ship being sent from America in May 1947 to take refugees to Palestine “illegally.” The Hebrew name for this blockade-running was Aliyah Bet, “Clandestine Immigration.” As the name indicates, it was not a matter of conspiracy. Everything had been done legally in America; and American dollars made it legal in Europe. As for keeping it secret from the British – well, we could always hope. But we’d be satisfied just to get the people out of Europe, even if only to Cyprus.

I took a launch out to the ship and, being the only passenger on the launch, I began talking to the man at the wheel.

“What ship are you on?” he asked.

The “Paducah.”

“Does she fly the Panamanian flag?”

“Yes.”

“She isn’t running Jews to Palestine?”

“No, we’re going to carry bananas.”

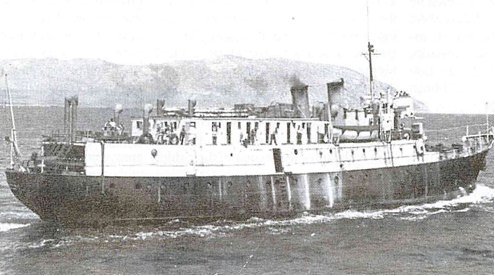

What was there to give our ship’s secret away? The harbor pilot didn’t notice it. He turned to our Jewish second mate with a puzzled look and said, “Christ, there are a lot of Jews on this ship.” The vessel was an ex-Navy training ship forty-five years old, speed 10 knots, tonnage 900. Even I couldn’t believe she’d hold fifteen hundred passengers, more than the Queen Mary, if we ever got that far.

I used to wonder about that. You would, too, if you’d been aboard, as we ploughed across the Atlantic. You might have gone down to the fire room and found me looking up at the boiler gauge glass. No water in it. The engineering regulations would be running through my head. If the fireman loses the water, cut out the fires and secure the boiler. When the boiler is cool, have it inspected for burnt-out or sagging tubes. “Cut out the fires, Len,” I’d shout.

“Don’t get so excited, Larry. The water will be coming up in a while.”

I’d shrug my shoulders and walk back into the engine room. Or, perhaps, you’d take a stroll on deck. The bosun, an ex-Navy boy from Brownsville, New York City, would probably be looking for “Buckshot.” We called him “Buckshot” because he had such a load of lead in his tail. He had left college to make this trip, and he still retained the student’s horn-rimmed glasses and four-syllable vocabulary. He was a Trotskyite and brought along huge stocks of literature to convert the crews and the refugees.

Six days out, we reached Fayal, in the Azores, where our first hitch developed. We were supposed to get oil and water there, but the British had control of all the oil on land and tied it up, and the agents demanded cash for the water and stores; so we were held up a week waiting for the money to come through. Finally we left, bound for Lisbon, where we were definitely supposed to get oil, and a few days later arrived and anchored in the Tagus River. Again it was impossible to purchase oil, so we got orders to proceed to Bayonne, a small port on the Atlantic coast of France, near the Spanish border. By this time the chief engineer’s report of the amount of oil left aboard was preceded by a minus sign, but luckily his calculations were wrong and we got into Bayonne under our own steam.

There we tied up next to another Haganah ship, the “Northland,” which was to accompany us until the end of the journey. Her crew was in such a confused state that we looked like a model of discipline beside hers. Their attitude was represented by Labal, a writer from Greenwich Village. It was claimed that he had come on the trip because he couldn’t keep up the twelve-dollars-a-month rental on his apartment in the Village. Most of his writings were a little too obscure to have a wide popular appeal; however, a story of his had appeared in “Death Magazine.” This was a journal of which only the first number had appeared, edited by Labal. Shortly after its publication he was forced to leave town to escape the printer who was dunning him for the bill.

Along with most of the other boys on the “Northland,” Labal had not gotten along with the captain. So with an ultimatum that it was either him or the captain, he left for Paris, where he continued to receive spending money from the Haganah. Eventually, Labal was triumphant. The captain caused too much trouble and was sent back to the United States. While our ship was anchored in Bayonne we walked the deserted streets. We never guessed how crowded those streets would be a month later when a six-day fete was held, with confetti-throwing, fireworks, bicycle races and dancing on the cobbled pavements. The fete really centered around the bullfights in the stadium, for there were many Spaniards and Basques in the area. Courses des vaches were also held, and cows were let loose in the streets to be faced by the amateur matadors of the town.

At first we seemed to be accepted as a cargo ship by the townspeople, but after a while our real purpose became known and French reporters and photographers began to appear. They asked us what the wooden shelves were for, and we told them we were going to carry bananas on them. The next day the Bayonne paper was headlined “Couchettes pour les Bananas” (Beds for Bananas), with a story that we were going to run refugees to Palestine.

Of course, the French officials had known all along who we really were. They now came out with a public statement ordering us not to load people aboard at Bayonne, which we’d never had any intention of doing. This was in July, just after the “Exodus” had been intercepted. The French officials “discovered” that it had left with faked visas and clearances from Setres. So they fined the shipping company which owned it $80,000. The same company owned the “Northland,” and it was to be held pending payment of the fine. We were afraid they might decide to hold us too, so we worked feverishly to finish the new water tanks and put in the air vents and bunks. We left all our good clothes and passports and papers for the Haganah to keep in France, and sailed at five one morning for a destination unknown to the crew.

As soon as we left the harbor we turned south, and the bets were our destination was to be the Black Sea behind the Iron Curtain. We were all tense as we approached the Straits of Gibraltar, since one ship destined to carry refugees had been seized there by the British. We timed our arrival at night, and we hugged the North African coast as far from the Rock as possible. We weren’t challenged and we went to bed, exultant at slipping through the Lion’s claws.

But the next morning, as I came off watch, I saw a British destroyer about a quarter of a mile behind us. There was no accident about that, as she’d been trailing us since daylight. Soon she began to overtake us and started signaling. The bosun started playing a record over the P.A. system, the popular song that goes “Welcome, welcome, we’ve waited and waited / and now we’re elated to welcome you home.” The DE [Destroyer Escort] flashed over the question, “Where are you bound?” and we answered, “Leghorn, Italy.” But she stayed alongside us while her crew lined the rail to look at us. A couple of our boys, in a playful mood, got out sheets and towels, dressed as Arabs, and salaamed towards Mecca. We were so close we could hear a couple of the English sailors say, “Blimey, they’ve got bloody Arabs aboard.” After a while she fell behind again and followed in our wake. About this time we found our condensers were leaking, which meant that our water would never last until our destination, so we entered Bohn, in Algeria, to take on fresh water. Our British escort waited patiently outside the harbor, like a private detective in a divorce case, and took up the trail when we left the next day. By the time we reached the Greek coast, they seemed a little incredulous when we signaled Leghorn as our destination. We finally left them behind at the Dardanelles, where naval ships couldn’t enter, and they flashed us, “Goodbye, see you again.”

Soon, however, our oil ran out and without electricity or running water we awaited the promised oil train. Eventually the oil appeared, the transport diminished from a train to a horse and wagon with a few barrels of diesel oil. We started up the boilers and had electricity for a few hours until we ran out again, and awaited the next load. However, we forgot all about these little inconveniences when John, our shu-shu [undercover] skipper, announced that he had gotten permission for us to go ashore. In a few minutes the ship was practically deserted, and we were all exploring life behind the Iron Curtain

We were lucky to be in Varna, since it was the leading resort in Bulgaria, and there were many people who could speak French, German and even English. Although they were always whispering about the secret police and the militia, all of them seemed to feel free to gripe to us about the new regime. I think that, eventually, everybody in Varna who talked to us asked if we could smuggle him out on our ship. Even the movie queen of Bulgaria, whom the bosun used to take around, said she’d give up her career to work as a housemaid in the States. Odd situations developed when our captain Rudy, an old Communist Party member, began telling these Bulgarians how wonderful their new regime was, and how decadent America really was.

There were quite a few Jews in Varna, but they didn’t have much to do with us. Our passengers were going to come down from Romania, as no Bulgarian Jews were allowed to leave the country. Unlike the Jews in Romania, these people, descendants of Spanish Jews who came there during the Inquisition, were needed in Bulgaria. There was never much anti-Semitism in Bulgaria, and during the war the Bulgarian Government, as an ally of Germany, was allowed control over its Jews. As a result, they escaped much more lightly than any other Jews within the German- dominated areas. Since most were well-educated, they were useful in peasant Bulgaria. The British had been putting pressure on the government, through the Allied Control Commission, to make us get out. Finally we were ordered to leave Varna, so early Friday morning we left and landed again twenty miles down the coat at Burgos. The Allied Control Commission didn’t meet over the weekend. The next week the Bulgarian Peace Treaty was signed and we were safe.

Soon we were joined by the “Northland,” which had finally been given clearance in France, and we awaited the refugees together. Each day they were supposed to be on their way; but weeks passed before we received word that the freight trains loaded with people would definitely arrive that night. The “Northland” was to be loaded first, as we still had to take on oil, but all of us were to go over to organize the loading, since it had to be finished before daybreak. It was D-Day for us, and we all shared the excitement of Davey, our fervently religious ex-Hebrew teacher.

At around midnight the train finally arrived and was shunted down to the dock. There were 3,000 refugees: old people laden with huge packs containing all their worldly possessions, youth marching to the rhythm of militant Hebrew songs, orphaned children, and right at the end appeared a woman with her child, born a few hours earlier in a boxcar. Davey, who was supposed to direct the people, began embracing each one of them. Rudy, our skipper, burst into tears, even though it wasn’t the Communist line. A soberer note was maintained by Charlie, our Gentile first engineer, who turned to me as the first refugee came up the gangplank, and said, “I’m not sure, but that guy looks like a Jew to me.”

Soon we were all busy trying to squeeze one more mama or child into those three-decker shelves. The people had expected to find Greek or Turkish sailors, so they were really surprised to find Jews, volunteer American Jews. John the shu-shu man said he wished there were fifty more of us, not because we were any good as sailors, but because we gave the people a lift. It took us five hours to finish loading, and at six in the morning the “Northland” pulled out, with the people aboard singing Hatikvah, the Hebrew national anthem. She dropped anchor in the harbor to wait for us to load, but the people thought it was in order not to travel on the next day, which was Yom Kippur. The deck of the “Northland” was thronged with people rocking in prayer, casting the sins of the year into the water. When their skipper Lewis appeared on deck with a skull cap and a prayer shawl, rocking (although not because of religious ecstasy), they were sure their fate was in pious hands; meanwhile, the oil train finally arrived, and the next night we loaded our own 1,500 passengers and set out. The sea was calm and the people seemed happy. They got two hot meals a day as well as cigarettes and chocolate, and the ventilation wasn’t too bad, even if sleeping conditions in the crowded wooden bunks were none too comfortable. Their main complaint was that they couldn’t wash except with salt water. There were plenty of doctors and nurses aboard, and we had set up a hospital. One of the boys even had his teeth drilled by a dentist who had brought along his equipment.

Most of the people were Romanians, although many were survivors of the German camps and others had been in Russia during the war. We even had some ex-heroes of the Red Army with boxes full of medals. Their attitudes towards the Soviets ranged from lukewarm to cold. All of them complained about anti-Semitism in Russia, particularly in the Ukraine, although some said it wasn’t the Government’s fault. Most seemed to take the Russian methods of government for granted, as ten years of suffering had made them a little hard-boiled. They could even joke about being sent to the soap factory. We didn’t have any native-born Russian Jews. Apparently it was impossible for them to get out.

Life took on a more serious note when we got through the Dardanelles, for the British destroyer was waiting for us there, and was soon joined by several other destroyers and a couple of light cruisers. As we passed between the Aegean Islands with the English behind us, they flashed us a message that the course we were taking would bring us dangerously close to mine fields. It was a terrible problem to the captain. Should he take their word? To us it seemed incredible that they’d try to delude us, but the captain decided to continue on the old course and we passed through safely.

All along we had been hoping to transfer our people to the “Northland” about a hundred miles off the Palestine shore, so that we could go back for another load. On the sixth night we got orders to standby to make the shift, but when the crew of the “Northland” tried to move their passengers below deck to make room for our people, they found there wasn’t enough room. The next morning the Hebrew flag, the Star of David, flew from our mast, which the bosun had greased so the British wouldn’t be able to get it down. A large sign was hung over our side with our new name, the Haganah ship “Geula” [Redemption]. The “Northland” also carried signs with her name, “Medinat Hayehudit” [“The Jewish State”].

We had large stores of wooden clubs aboard and all the younger people seemed eager to fight off the boarding party, but we received a radio message from Palestine to offer no resistance. Around noon we made a broadcast to the Haganah radio station, which rebroadcast it throughout Palestine. Some of the people sang Hebrew songs. Chaim, our official orator, made a speech in Hebrew, and some of us got together and wrote a speech in English. Or rather, we let Lippy, our ex-social director of Borough Park Jewish Veterans, write a three-thousand-word speech, which we got down to the required laconic three hundred words by cutting out some of the clichés.

By then we could see the coast of Palestine in the distance, and the British marines were lining up on the landing platforms built on the destroyers. To disguise themselves, our crewmen were all busy getting ragged clothes from the refugees, adopting babies and even complete families, and went around muttering Yiddish phrases to themselves. I noticed a young rabbi, complete with a beard, black coat and hat, prayer shawl and a Bible, which he was reading to a group of children. As I approached, without changing his intonation, he broke into some profanity known only in Brooklyn. It was Lou the atheist, one of the boys who’d been on the “Ben Hecht” and been held by the British. Now I knew why he had nursed that beard on the journey.

About ten miles off the Palestine coast, south of Haifa, the British came alongside us and told us to turn back. There was no answer to their request, so they began throwing tear gas grenades and then boarded our ship. Below, we felt a crash as the destroyer hit our sides. We sabotaged the plant, rushed up the emergency ladder, and mixed with the people on deck. The British had gotten control of the wheelhouse without violence, and now they stood and looked at us, a little curious and a little worried.

The “Paducah” being boarded by British marines

John and Chaim distributed the remaining food and cigarettes to the people. It was night by the time they towed us into Haifa harbor. Spotlights glared on us as we pulled in. “Rabbi” Lou and I were among the first to get off and go through the gauntlet of the search and D.D.T. job. The British were “Red Devils,” First Airborne troops, mostly bored boys about my age. They directed us in English and it was hard not to understand when a sergeant told Eli, “You look just like my stupid cousin.” Another looked at Lou and asked, “What’s that?” and the sergeant answered with an air of wisdom, “Oh, that’s a very religious Jew.” We were worried about “Heavy,” our three-hundred-pound mate, but we saw him climb onto the English ship with John the shu-shu, and we knew he was all right so far.

The boats that were used to take us to Cyprus were cargo ships with part of the deck caged off and a couple of large rooms with rows of benches. By some ironic twist they were called “Empire Rest” and “Empire Comfort.” When we got aboard the “Empire Rest” we first realized the gratitude our people felt towards us. As soon as we were past the British guards, a score of them ran around trying to make us comfortable, bringing us the crackers and tea the British had handed out, making room for us to lie down on the benches, giving us their coats, and even apologizing for the shrew who sat across from us yelling at her husband and accusing him of making a scene whenever he opened his mouth to say “Yes, dear.” I regretted then the harsh answers I’d given some of those people on the ship when they’d asked for favors, or when their manners weren’t too good. It was nice being a hero and part of the legend of their ship, the “Redemption.”

The British guards allowed us to go up for fifteen-minute stretches of air in the caged-off parts of the deck, women and children getting preference. As we waited at the door the English corporal said, “Don’t look at me, it’s that bastard up there who won’t let you out,” pointing to the sergeant at the top of the stairs. As we left the ship at Famagusta, Cyprus, all the soldiers said goodbye to each of us and patted Lou on the back and said, “Take it easy, Pop.”

When we got ashore a major asked in English for four volunteers to watch the baggage. As no one came forward, he picked them out of different parts of the crowd. Purely by chance he chose Lou, our Spanish steward Eli, and me. He asked us if any of us spoke English, and we all looked blank. Then he muttered something about “These Jews only speak English when they want a cigarette.” Finally our Spanish cook said, “I spik a leetle Anglish.” So we listened to the major’s English and pretended to understand when the cook translated into Spanish. We were loaded into trucks and taken to the other side of the island near Lanarca, where the refugee camps were. There we passed through the army and C.I.D. control, which consisted of a search for arms and money, which were deposited by the British.

As soon as “Heavy” entered, a soldier said to him, “What the ‘ell are you doing ‘ere, Yank?” Heavy just looked aloof. But when he stripped and revealed the American eagles, anchors and mermaids tattooed on him from head to foot, they took him aside. All he would say was the Yiddish phrases we’d taught him, but they found a draft card he’d sewn into his pants, so he decided he might as well talk English. He was taken to the major’s office where a girl from the camp was working. Later she told us that the major had asked him what he was doing there. “Heavy” answered, “I’m going to Palestine”.

“You’re not Jewish, why do you want to go?”

“Everybody’s going.”

“Well, we’ll let you go back to America if you tell us who the other crew members are.”

“I’d like to be alone with you, Major”. The major got up…

and I’ll knock your block off”.

They put “Heavy” in the guardhouse overnight and he had another interview with the major. The major told him they were going to put him in the camp with the rest of the refugees to see how he’d like it for a couple of years. He was still there, watched by the British. He had filled out deportation papers, but those things seemed to go slowly. In the meantime, the refugees waited on him hand and foot, and the Haganah gets a bottle of cognac to him every few days, but none of the other Americans could see him for fear of being identified.

Some of the other boys had close calls, for there was a Romanian Jew in the control, a member of the British Army, who could speak all the European dialects. He seemed to have worked with the Nazis in Romania, and the British themselves didn’t have much use for him. After passing through control, we were driven into the camp, issued a blanket, a plate, knife and fork, and left to our own devices. The British left the organization of the camps entirely up to the refugees, with the help of the Joint Distribution Committee and the Jewish Agency. We seldom saw any British soldiers except those guarding the barbed-wire fence and driving food trucks.

The camps consisted of tents and Quonset huts and a few shower huts. After a refugee had been on the island for ten months, he’d usually acquired space in a Quonset hut and had probably made himself fairly comfortable. If he was with his wife, they cooked their own food, but had to eat in the mess halls and share kitchen duties. Food consisted mainly of dehydrated potatoes and macaroni, with some meat, local vegetables, coffee and margarine. It wasn’t on a starvation level, but most people’s health was fairly low. Most of us got dysentery and boils during our two months’ stay. The starchy diet seemed to have a peculiar effect on the women – they all become very well developed in the upper chest. In fact, there wasn’t a girl on Cyprus who didn’t put Lana Turner to shame.

The boys of the crew lived together in a Quonset hut, easily distinguishable by its sloppy interior and the large wine barrel inside. The Haganah bought us one hogshead of the local vintage each week, and the celebration we held when it arrived was our way of keeping track of time. The refugees amused themselves more constructively: they played soccer, practiced Haganah commando tactics, held amateur theatricals, or danced Palestinian folk dances around a bonfire. We had heard the British claim there were Soviet agents among the refugees. However, up to now, the British hadn’t revealed how they found this out. One thing is quite certain: they did not identify any Russian agents among the immigrants on the ships captured. They hadn’t even bothered to look. The British C.I.D. and army “control” of the refugees going to Cyprus and entering Palestine was so inept that the thirty-eight American crew members of the Haganah ship “Redemption,” including me, passed through it without being identified. Our attempts to disguise ourselves as refugees were definitely amateur. “We were spotted as Americans by the people on Cyprus before we opened our mouths. Did anyone know of any Soviet agents? The answer was “No.”

There were many people who had been in Russia, but most shared the opinions of an American Jew, an ex-Wobbly who’d jumped ship in Russia in the early ‘30s. Too independent-minded, he had been put away in Siberia to cool off. He’d been released to work during the war and got across to Romania where he’d joined the illegal immigration movement. He was only 40, but completely broken in health and spirit. Those who supported Stalinism were members of a Zionist political party called Hashomer Hatzair, who numbered perhaps 15 percent of the refugees. While we were on Cyprus they celebrated the anniversary of the Russian Revolution by marching around with pictures of Marx and Lenin. But most of the members I knew winked as they marched past me. They took its politics with a grain of salt. They had joined the organization in Rumania because its members were the quickest to leave Europe. The Communists preferred to have sympathizers leave rather than those who were openly disaffected. And in spite of its sympathy for Stalinism, Hashomer practiced real and democratic communism on collective settlements in Palestine. Most of the pro-Russians were young boys and girls who had spent their lives in the German prison camps until the Red Army had released them.

The technique of getting us out of Cyprus was simple. The list of 750 refugees who were allowed to leave each month was made up on the basis of priority of arrival. We were to assume the names of people on that list who were therefore set back a month. The people who were supposed to leave had already waited about a year, but it was understood that the sailors should leave first. Still, there weren’t enough places for all of us, so four boys volunteered to stay behind until the next quota. Labal, the Greenwich Village writer, was the first to volunteer. He was getting three square meals a day without working and was a hero to boot.

A few days after we arrived, the crew of a previous ship, the “Despite,” left. The “Despite” was a small landing craft which had sailed from Italy flying an Egyptian flag. They had been about 50 miles away from Palestine, still unsuspected by the British, when the captain noticed a light blinking in the aft part of the ship. A few hours later the British boarded the “Despite.” A girl, recognized as the one flashing the light, stepped forward and proceeded to identify the crew members. They were locked up in the hold. However, in the mix-up of unloading in Haifa, the crew broke out and mixed with the refugees and the British let it go at that. That girl went to England. Her half-sister, who was in Cyprus, said her father was a British military attaché in Hungary, and their mother was Jewish, but she had never suspected her sister of working with the British. Of course the Haganah was interested in finding her, although the red-haired young skipper of the “Despite” wouldn’t say what would happen to her if they did.

One of our Gentile volunteers, Dave Blake, was also for staying behind. Dave was a graduate chemist who wanted to live as a farm worker in a communal settlement in Palestine, where he felt life would be more natural and just than in America. He was always a little distant from the rest of us. We couldn’t understand a man who studied Hebrew when he could have gone ashore in France to chase women. Nor could we understand it after we reached Palestine, when Dave took the $100 the Haganah gave each of us and went straight to a settlement and gave the money to the communal treasury. When we visited him there he was working hard in the fields and speaking a beautiful Hebrew. He seemed much happier than he’d ever been with us.

As the ship pulled into the dock, we began looking around for methods of escape, but we all found ourselves on the buses going to Atlit. British tanks and motorcyclists were guarding us. There were no guards on the buses, and the drivers were Jewish. We told the driver we were sailors and wanted to make a break. He nodded his head and soon all the buses stopped, each one bumping into the next. The door opened and, as I later learned, 16 of us streamed out. I was the first man out of our bus. I still don’t know whether I jumped or was pushed by “Action Jackson” behind me. We walked straight across the street into an Arab garage where we asked for parts for a ’38 Ford. When we saw the convoy had passed on, we walked down the street until a car stopped and someone asked us in Hebrew how to get to a certain street. Instead of answering, “I’m a stranger here myself,” we climbed into the back seat and asked him to take us to an address in the city.

In a few minutes we were safely settled in a room in the best hotel in Haifa. There we found eight of the boys. The others had been captured and sent on to Atlit. Everything was new and wonderful to us in the hotel – warm water, clean linen, beds, and finally a huge roast beef dinner.

Comments by George Goldman, who also served on the “Paducah” with Kohlberg:

“Beds for Bananas” by Larry Kohlberg is a first-rate recounting of his experiences as a volunteer crew member aboard the Haganah ship the “Paducah,” later renamed the “Geula” [Redemption]. She was staffed by licensed Merchant Marine officers and manned by a volunteer crew of college students, yeshiva-bochers, some World War II veterans from the Navy and Army, and several professional merchant seamen. What they lacked in experience, this motley crew made up in enthusiasm and dedication. Their mission was to carry Holocaust survivors from the displaced persons camps of Europe and to try to smuggle them past the British blockade of what was then British-controlled Palestine.

The voyage, though supposedly clandestine, was not a very successful secret operation. From the very beginning it was bedeviled by British operatives and interference. We did, however, get over 1,300 DPs as far as Cyprus and that was something of a success.

Larry covered the highs and lows of what turned out to be a ten-month saga. This however is only an appetizer for a fuller and more detailed account. I recommend the book, “Running the Palestine Blockade – the Last Voyage of the Paducah” by Captain Rudolf Patzert, Naval Institute Press, 1994.

Source: Author – Laurence Kohlberg, (American Veterans of Israel Newsletter: Fall 2006)

Link to story of Walter “Heavy” Greaves