Birthplace: Berlin

Aliya date: May 2008

Occupation: Retired handbag manufacturer

Family status: Single

The face of a handsome young Mahal soldier is framed in a photograph hanging in the hallway of Victor Beresticki’s Jerusalem apartment. Now an octogenarian, that soldier today clearly recalls the 10 months he slept in a stifling tent in the Beit She’an Valley while serving as a volunteer fighter for the fledgling Jewish state.

The face of a handsome young Mahal soldier is framed in a photograph hanging in the hallway of Victor Beresticki’s Jerusalem apartment. Now an octogenarian, that soldier today clearly recalls the 10 months he slept in a stifling tent in the Beit She’an Valley while serving as a volunteer fighter for the fledgling Jewish state.

A lifelong Zionist with a colorful life story, Beresticki regrets that it took him so many years to make the move from London. But it’s never too late to start over. “I arrived on May 10, and I tell everybody that’s my real birthday,” he says.

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Victor and his brother and two sisters were born to religious Polish expatriates living in Berlin. Before he was 11, he’d witnessed two soul-searing incidents: Adolf Hitler saluting from an armored Mercedes as his convoy drove right by the Berestickis’ house and the November 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom.

By early 1939, the Berestickis were in the midst of a years-long wait for their American quota number to come due. An ominous letter from the Gestapo persuaded them to abandon that plan and seek refuge immediately with a relative in London.

On one stop of the difficult journey, Victor’s father was offered a cantorial position in Antwerp. His mother presciently urged her husband to forgo it and get as far from Germany as possible. Already in poor health, she died soon after their pre-Pessah arrival in England.

Because their father also was not well, Victor and his brother first went to stay with a local rabbi and then were evacuated to the countryside with many other children as the war loomed. Sheltered by a gentile farm family for 10 months, the boys ate vegetables and the cooked kosher meat their father brought them every week. Just when he decided it was safe to take his sons home to London, the yearlong Blitz began.

“We were bombed day and night,” Beresticki recalls. “We got fed up sleeping in air-raid shelters where there was no air to breathe, so we slept in our beds and took a chance. I still remember watching the panorama of planes flying past.”

A LONG ROAD TO ALIYA

After studying at the Gateshead Yeshiva for two years, Beresticki became apprenticed to a diamond cutter for the next four years. Through his Mizrahi youth group, he was quietly recruited to aid newborn Israel in May 1948.

He set sail for Haifa from Marseilles on the steamer Pan York – a dilapidated Panamanian vessel originally built to haul bananas – with 2,600 war refugees and other passengers including a contingent of Moroccans (“I never knew such a thing as Sephardi Jews,” he says). A model of this ship, which successfully delivered its human cargo despite Britain’s best efforts, sits atop a living-room bookcase in Beresticki’s apartment among other memorabilia.

As members of the Mahal Brigade for overseas volunteers, Beresticki and six friends were posted to Beit She’an, where they withstood extreme heat during the day and extreme cold at night in addition to dangers from the enemy. “The Iraqi army was directly underneath us,” he recalls.

His British passport expired while he was in Israel, but after the war Beresticki got to France with the help of the government, which put him on an army transport along with what he calls “other hard-core cases.” For three months he was stranded in Paris, where he polished his conversational Hebrew by speaking with his Hungarian-Israeli roommate. Eventually, he reentered Britain as a new immigrant and was reunited with his father.

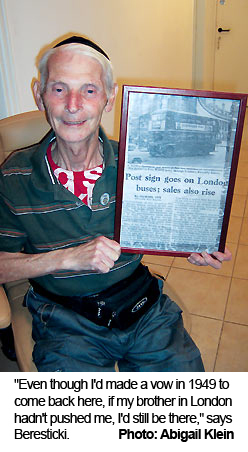

After four years cutting diamonds, he came into his father’s successful handbag factory and built up a retail business. In the 1960s, he voluntarily distributed the overseas edition of The Jerusalem Post each Wednesday to more than 100 news agents, and also placed prominent Post ads on London’s buses and public squares.

His father and sisters made aliya around 1968. “Every penny I earned – that didn’t get stolen – went toward trips to America or Israel,” says Beresticki, who visited Israel a total of 70 times. “If you would have told me when I was 20 years old that someday I’d be sitting on a plane with a Star of David on it, eating kosher food, I would not have believed you.”

When their father died in 1983, the siblings pooled their inheritance to help Victor buy an apartment in Bayit Vagan. Still, it would be another 25 years till he moved into it permanently.

“Even though I’d made a vow in 1949 to come back here, if my brother in London hadn’t pushed me, I’d still be there,” says Beresticki. In hindsight, he reflects that he put off aliya as a result of factors including discouragement from peers and his own “evil inclination” to stay put.

DAILY LIFE

Beresticki inherited not only his father’s and grandfather’s strong faith, but also their love of the written word.

He owns a worn set of Talmud that his father saved from a Nazi book-burning, and he self-published his paternal grandfather’s long-hidden handwritten manuscript, Shamati Mirebbe, through Mossad Harav Kook. He’s written five autobiographical books “waiting to be published,” including one detailing his dramatic experience in Yamit during the last days of Israel’s sovereignty in the Sinai.

Though arthritis has curbed his formerly athletic lifestyle, Beresticki does his own cooking, cleaning and marketing. He lives on a British pension and his National Insurance allotment.

“You know what keeps me going?” he reveals. “Every night I go to the Western Wall.” After praying, he attends a Talmud study group there and comes home at 1 a.m.

“I make myself a nice meal, listen to the radio, and go to bed at 2:30,” he says. At 7 a.m., Beresticki has a hot bath and then goes to morning services. He often visits with a friend afterward, telling his life stories – which he also enjoys sharing with bus drivers and passengers, as well as students at Yeshivat Netiv Meir next door to his apartment building.

He sleeps again in the afternoon before his nightly foray to the Old City.

THOUGHTS ON ALIYA

The process of immigration was not all smooth sailing. First there was the thorny problem of locating his birth certificate in Berlin. Then there was the matter of gaining an exemption from a medical exam; Beresticki has avoided doctors since suffering a particularly bad reaction to the anti-cholera injection he received prior to Mahal. Finally, he had to liquidate his retail stock and ended up donating 500 handbags to charity before his departure.

“You’ve got to have that feeling inside you,” he says by way of explaining his determination to make it work.