(Note. Readers of this article who served in radar during 1948-49 and who are able to contribute additional information, are asked to please write to worldmachal@gmail.com)

Unlike other units, there was no radar nucleus at all in Israel in 1948. It had to be built from scratch. Nor were there any local personnel experienced in the subject as the British had barred Palestinian Jews from working on radar. . Consequently volunteers from abroad with radar experience were especially valued.

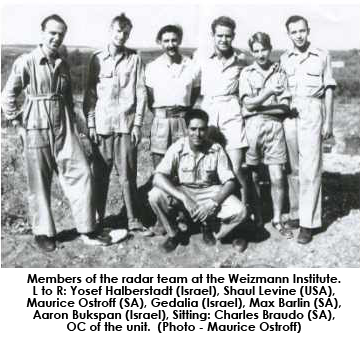

Fortunately, the early volunteers included a number of WW2 radar veterans from South Africa, USA, Canada and Britain, who established the first radar unit named 505 squadron, under the aegis of the nascent Israel Air force,. The unit was commanded by American radar expert, Moshe Ettenburg (Eitan). His second in command was Charles Braudo, originally from South Africa and a researcher at the Weizmann Institute prior to joining 505.

Radar had been a carefully guarded secret during WW2 and the Machal radar veterans applied their disciplined approach to secrecy to such an extent that the very existence of this hush-hush unit was unknown to many IDF higher ups. To this day little is known about Squadron 505 among Army and Air Force personnel and historians, although some of the early radar history is mentioned in a restricted circulation book in Hebrew, “The Eyes of the State” published by the Department of Defense in the Heritage Series of the Israel Air Force.

Radar had been a carefully guarded secret during WW2 and the Machal radar veterans applied their disciplined approach to secrecy to such an extent that the very existence of this hush-hush unit was unknown to many IDF higher ups. To this day little is known about Squadron 505 among Army and Air Force personnel and historians, although some of the early radar history is mentioned in a restricted circulation book in Hebrew, “The Eyes of the State” published by the Department of Defense in the Heritage Series of the Israel Air Force.

The first radar station constructed at the Weizmann Institute, codenamed Barak, was installed at kibbutz Glil Yam out in the country in those days. Today Glil Yam is almost in the centre of Herzliya. Canadian Morry Smith was in charge of the station.

Smith recalls: We were a motley crew: three technicians and about a dozen girls to operate the equipment, about half of them Israelis, the others, recent immigrants – their only qualification that they speak English. So primitive was the equipment that the usual procedure was for two girls to be on duty, one inside watching the radar screen, the other outside watching the skyline so that she could tell the operator where to turn the antenna if she spotted an Egyptian plane approaching. His wife Miriam and her closest friend Erika Walden, now living in New York, were both operators at this station.

Aaron Bukspan, a radar technician on the Barak station, recalls an amusing incident. He tells that on one occasion a technician crossed the wires connecting the rotating antenna to the position plan indicator (the PPI), with the result that the operators were puzzled by echoes of ships in the Judean hills.

A second small group of radar men was assigned to a laboratory at the Weizmann institute, which they shared with a few members of Kibbutz Hatzor in the south. When the Egyptians, 4 miles away, threatened the kibbutz, it evacuated its children and moved its small radio factory, run by a few American electronic experts, to the Weizmann Institute. The kibbutzniks, experienced as they were in electronics, though unfamiliar with radar, were very helpful in discussing possible solutions to complex technical problems.

For the Machal volunteers, the kibbutzniks were as interesting as the work challenge. Ostroff was fascinated by the pure socialism practiced by the kibbutzniks and when night work permitted, he accompanied the men back to the kibbutz. With the Egyptian army situated only four miles from the kibbutz, the kibbutzniks were anxious to get back before nightfall in case of an attack. They were given bus fares but mostly they hitchhiked daily from Hatzor to the Weizmann Institute. When they were successful in hitchhiking they would return the unused bus fares to the kibbutz.

Among the group Maurice Ostroff and Max Barlin had served as radar technicians in the S.A. army. Eli Isserow was a fitter and turner, though with his gifted hands, no ordinary one. “Build radar” the men had been instructed. None had experience in design or construction of radar. Bits and pieces salvaged from deliberately damaged and abandoned RAF equipment were eventually received and the second rudimentary Israeli radar started taking shape..

Building equipment would be very well – but it would not be of much use without operators and a Filter Room. Because of his experience in World War 2 Jack Segall was entrusted with the task of setting up this infrastructure.

A large plotting table was constructed with a map of Israel and surrounding countries divided into segments in accordance with a code aptly code named the Segol (Hebrew for Purple), a play on Segall’s name. Aaron Bukspan was sent to the newly established military camp at Tel Litvinsky (where Tel Hashomer hospital is now located), to recruit and select trainees to become radar operators at the as-yet non-existent stations would use the Segol code for maintaining security in reporting positions of ships and aircraft detected by radar. .

A training school for operators was established in Haifa, a course was prepared and dummy models of radar sets were constructed for training purposes. Jack Segall assisted by Yetta Golombick conducted the courses. The trainee operators were mostly female. Segall’s wife, Janie, comments today with a twinkle in her eye, “Over the years I have had to put up with strange women accosting Jack in supermarkets or in the street – having recognized him from their days as his trainees”. Among the women on the first operators course were Batya Aboutbul, Zehava Blau, Bella Raizes, Miriam Smith and Erica Walden.

A training school for operators was established in Haifa, a course was prepared and dummy models of radar sets were constructed for training purposes. Jack Segall assisted by Yetta Golombick conducted the courses. The trainee operators were mostly female. Segall’s wife, Janie, comments today with a twinkle in her eye, “Over the years I have had to put up with strange women accosting Jack in supermarkets or in the street – having recognized him from their days as his trainees”. Among the women on the first operators course were Batya Aboutbul, Zehava Blau, Bella Raizes, Miriam Smith and Erica Walden.

The first radar technician-training course was conducted by Reuben Joffe at Sarona (now the Kirya). 15 radio technicians participated including Israelis, Shmuel Reiman (Rimon) later to become a station commander and eventually Commanding Officer of 505, brothers Azriel and Leon Gattenou, Aaron Bukspan (later to take over as commander of station Gefen from Monty Mymin), Moshe Ben Sira and Amos Bruner (Ben Rom) who remained in the permanent force and was sent later for advanced studies with the RAF in England.

Meanwhile the team at Weizmann Institute, were working feverishly on model 2. Authority had brought them bits and pieces of detonated radar equipment recovered from RAF airborne junk. Anxious to produce results as soon as possible, the men developed a routine. The mechanical workshop was not available to them by day as it was then used for the manufacture of light arms. They worked 12 to 14 hours daily in two consecutive shifts, by day in the electronic workshop and after a brief break for a meal, at night in the mechanical workshop where Eli Isserow was to show his genius.

The basic equipment was adapted from a discarded WW 2 air to surface vessel (ASV) unit. Ostroff, a radio ham, knew something about antennas and he designed a large array to extract the last ounce of energy from the low power set.

The big day came for testing. The men carried the set to a roof. The large antenna, dwarfing the set, was erected and the set switched on. An echo came from the Judean hills. The men were learning.

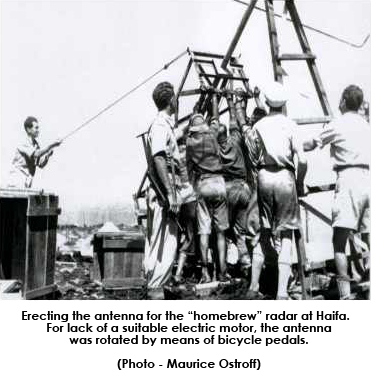

Then came the day to put it into operation. The “Heath-Robinson” equipment was transported to Haifa and installed at a former British camp next to the French Convent. The station under command of Max Barlin assisted by Machalniks Ostroff and Isserow, Mort Kaplan and Stan Berger and Israelis Aaron Bukspan and Micha Diensfrei was soon in operation. For lack of a suitable electric motor, a contraption comprising bicycle pedals, sprockets and a chain, had been built enabling the antenna to be rotated by hand.

By the time the Haifa station was successfully installed and left under Barlin’s command, the Israelis had gained control of the former British army base at Sarafand (Tsrifim). 505 squadron was allocated premises in the air force technical base there. Reuben Joffe was appointed Chief Technical Officer and Base commander, Jack Segall in charge of operations and Abe Goldes in charge of the E&M workshops responsible for all mechanical and electrical equipment assisted by top-rate mechanics, Hungarian, Mike Miller and South African, Max Kangisser. The main task of the E&M department in conjunction with the radar department under Reuben Joffe, was to build transportable radar stations. Sam Shaya was in charge of civil engineering for the camp and radar stations and Dorothy Jackson was head of the womens’ section. Yetta Golombick was in charge of operator training.

Having completed their task at the Haifa station, Ostroff and Isserow were ordered to report to Sarafand, where, they were told, a surprise awaited them. At Abe Goldes’ E&M department they were shown a large crate marked “food” received from the USA and on opening it, they found an almost complete microwave radar of the type used on US torpedo boats, which had been acquired on the open market in the USA as obsolete war stores disposal junk. The men were delighted even though the equipment was less than ideal for ground based operation.

Ostroff and Isserow were told that a mobile radar unit had become an urgent necessity. They were given three ex-British army trailers and charged with adapting the radar, fitting it in the trailers complete with plotting table, portable power plant and mobile workshop as soon as humanly possible. The power plant was a lawn mower motor adapted under the genius of Sid Suttner with the aid of Miller and Kangisser. Working day and night, the station, code named “Gefen”, was completed and put in operation within a matter of weeks, its first location being at Bat Yam with Ostroff as station commander.

The Haifa station and “Gefen” were later to participate in a much publicized incident relating to the downing of air intruders, later found to be British. This is what happened.

On January 7, 1949, the day on which a cease-fire came into effect, five RAF planes overflying Israeli territory were shot down: four by the IAF and one by ground fire. Dov Judah, Syd Cohen and Boris Senior were close to the event, which had a mysterious prelude starting in October 1948. During the month a reconnaissance plane had flown high almost daily over Israel. It was hardly distinguishable and the IAF men could just make out the plane’s vapour trails. The IAF’s fighters could not reach above 14,000 feet. Efforts were made to keep up a standing patrol and to intercept the plane, but this proved impossible. The impression was that the plane was Arab. It was enjoying a free run over the country, photographing at will. Nothing could be done about it. Nevertheless Syd Cohen left standing instructions, with Ramat David to keep him immediately informed of its observations.

On November 2, the intruder was detected by the makeshift Israel radar developed with few resources by squadron 505. On watch at the mobile radar station “Gefen”. commanded by Maurice Ostroff, were Adam Babitz, an Israeli who had gained his radar experience in the Polish army and South African, Barney Dworsky. They sighted the aircraft at 13:20h, plotted its track and immediately passed the information to the recently created filter room in Tel Aviv, headed by South African Yetta Golombick.

The track was followed by the station in Haifa which had been constructed by the radar group at the Weizmann Institute. All the equipment was makeshift; none of it originally designed for ground controlled aircraft interception. The radar people, continuing to maintain their low profile, were satisfied with the results of their efforts.

An American non-Jewish pilot went up in a Mustang to intercept the plane. Syd Cohen, standing in the Control Tower at Hatzor, watched the closing distance between the two. Wayne Peake, the American, came in from behind the intruder. Both were little dots in the sky. There were bursts of fire and then Control Tower heard Peake on the radio exclaim: “My goddam guns have jammed.” What actually happened was that in the short burst he had used up the little ammunition he had. The IAF was short of Mustang ammunition and distributed it sparingly.

The recce plane continued its flight. The Mustang broke away to come down. Suddenly Cohen noticed that the vapour trails of the intruder plane were getting thicker. It turned towards the sea, burst into flames in mid air and fell out of the sky in pieces. Ezer Weizman jumped into an Auster, flew out to the coast but could spot only one piece of wreckage. Identification proved impossible.

The identity of the plane was confirmed nine weeks later – thanks to a question put by Mr. Winston Churchill to Prime Minister Clement Attlee in the House of Commons. The plane was a RAF Mosquito. The disclosure was a consequence of a series of events on January 7 when the IAF met intruding RAF Spitfires and Tempests four times during the day and engaged them thrice. Air force documents disclose the following:

The identity of the plane was confirmed nine weeks later – thanks to a question put by Mr. Winston Churchill to Prime Minister Clement Attlee in the House of Commons. The plane was a RAF Mosquito. The disclosure was a consequence of a series of events on January 7 when the IAF met intruding RAF Spitfires and Tempests four times during the day and engaged them thrice. Air force documents disclose the following:

In the early morning, two of our planes flown by American “Slick” Goodlin and Canadian John McElroy, both WWII aces, spotted three enemy fighter planes. In the encounter, each of them shot down one.

Later, another group was engaged by Boris Senior and Canadian Jack Doyle, flying Mustang P51 fighters, also believing them to be Egyptian. Senior succeeded in firing a burst and possibly damaged one.

On the third occasion, two of our planes, one flown by Arnie Ruch, ran into eight of theirs, but no contact was made.

In the afternoon twelve were spotted. The encounter was dramatic. Dov Judah at Operations gave the order to tangle. Syd Cohen happened to be at Operations at the time. Four IAF planes led by Ezer Weizman engaged the twelve. The pilots, of the other three Israeli planes, John McElroy, and the Americans, Bill Schroeder and Caesar Dangott. Two of the intruders, whose pilots lacked combat experience, were downed by McElroy and Schroeder, making McElroy’s score for the day two.

The fifth RAF plane downed that day fell to a 82nd battalion tank gunner, since identified as British non-Jewish volunteer, Johnny Dawson. This made the events of Jan. 7th almost an entirely non-Jewish affair.

Melville Malkin, then in an artillery unit about 1,000 meters from the Rafah crossroads, was one among the scores of South Africans who saw the British planes hurtling down. Palmach jeeps went out to find the pilots descending with their parachutes. Dr. Barney Sandler, of Rhodesia, joined the interrogation group. The British fliers were surprised to meet this “Englishman.” They were taken to a casualty station in charge of Ossie Treisman, thence to Beersheba where the military surgeon was Dr. Wilfred Kark, also of Johannesburg, thence to Tel Aviv for further interrogation and medical treatment. An English-speaking doctor treated the facial injury of one of them. “Is the whole English-speaking world in Israel?” the now completely bewildered pilot asked.

Then the political storm broke. What were RAF planes doing over Israeli territory? The London Observer attributed the disaster to the “pathological anti-Israel obsession” of Ernest Bevin, Britain’s Foreign Minister, which “makes him persist in his blundering errors…”

Machalniks in 505

From the recollection of former members, Squadron 505 included Israelis, Asher Ben-Natan (squadron adjutant), Aaron Bukspan (later to become station commander of “Gefen”), Adam Babitz, Aaron Fass, Gavriel Shutz, Judith Tiefenbruner , David Ezrati, Shosh Fisher, sisters Rina and Batya Aboutbul, Shmuel Winik, J. Kevin, E. Ecker, Leo Goldstein, Yoram Boem, Yosef Druch, David Munweis and Al Sheinfeld.

Volunteers from abroad included Americans Joe Heckelman, Max Fishman, Myer Tannenbaum, Joe Ehrlich and Dave Orloff and Canadians Meyer Naturman, Morry Smith, Myer Cohen, Sam Morris and Al Lieberman. Volunteers from Britain included Jack Levy, Zeev Rowe, Jerry Solowitz, Lottie Kosses, Dorothy Jackson, Sam Green, Max Rose, Lou Friedman, Solly Chinn, Esther Tauber, Daphne Cohen, Sylvia Grodentzik and PT instructor Vidal Morowcowa (later to marry South African Mishy Fine) and from India came Yehuda Digorkar. South Africans included Jack Segall, Reuben Joffe, Sid Suttner, Abe Goldes, Mishy Fine, Max Kangisser, Maurice Ostroff, MaxBarlin, Eli Isserow, Ralph Lanesman, Barney Dworsky, Effie Levy, Monty Mymin, Abe Berkow, Mendel David Cohen and Lucien Henochowitz.

Ralph Lanesman relates that a significant number of Machal personnel were involved with Squadronn, 505 until at least mid-1949 on stations that operated for a while at Hirbiya in the Gaza strip. as well as from the Tegart Police