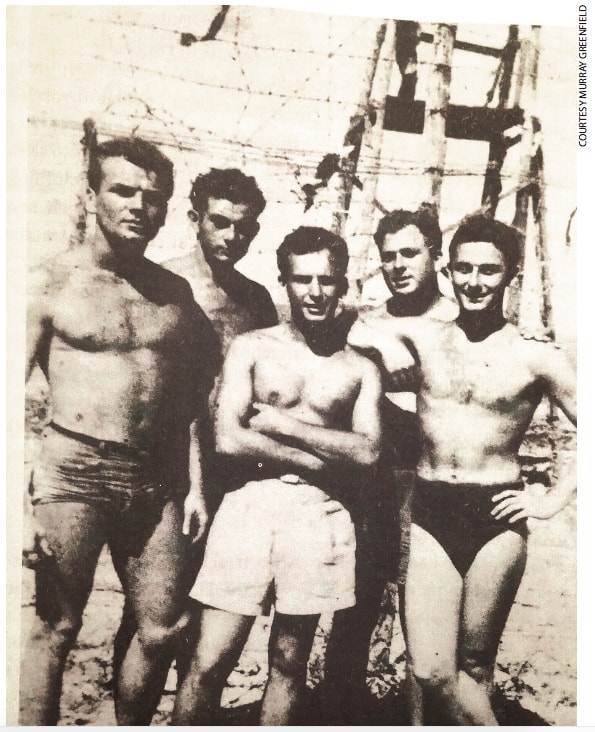

SOME 70 years ago, I was among a group of men who who sailed on a ship named Hatikvah (The Hope) to British Mandato- ry Palestine during what was called Aliya Bet, when we were caught by the British and incarcerated in Cyprus. When another ship carrying immigrants, mostly Holocaust survivors, the Exodus, was infamously cap- tured by the Royal Navy and its passengers deported back to Europe, the Hagana decid- ed to act.

First, it decided to dig an escape tunnel from the camp in which we were incarcer- ated in Cyprus. Three Americans took part in this project. Working with two refugees and a Jewish commander from Palestine, they started the excavation in the floor of a large tent at the edge of the camp. Their goal was a clump of trees some 150 feet away, beyond the fence.

For a groundbreaking ceremony, the Pal- estinian poured wine onto the earth floor and attacked it with a pickaxe. The men dug a shaft about 10-feet deep and then tunneled toward the fence. Every night, they dug in- side their tent, using water from the camp supply to moisten the soil and hold down the dust. After the excavated soil piled high in the tent, they began removing the excess earth in gunnysacks and dumping it into the camp’s latrines.

After about two weeks, the tunnel was about 30 feet long and extended beyond the fence. At this point, the American volunteers were given a new assignment. Others com- pleted the tunnel, which the Hagana later used for escapes.

The new task of the American tunnel diggers was to prepare a bomb capable of sinking a British prison ship. The bomb would have to be smuggled aboard ship and detonated at the proper time. Cyprus was a logical base for such an operation, since British prison ships called there frequently to pick up refugees permitted to enter Pales- tine under the quota maintained by the Brit- ish. In each shipment of refugees leaving Cyprus for Palestine were individuals des- ignated by the Hagana. For them to bring a bomb aboard would not be easy, but it could be done.

To make the bomb, the Hagana sent explo- sives (gelignite, detonators and other mate- rials) to Cyprus. One night, the Americans cut the barbed wire and slipped out to pick up the materials for the bomb. British guards spotted the Americans but failed to catch them. The next day, the British authorities announced harsh measures would be taken until the escapees turned themselves in. Ha- gana operatives composed a note saying they had tired of being cooped up and had gone into town for some fun.

They enclosed some Cypriot currency and signed false names to the note. Nothing further was heard about the incident, and the Hatikva crewmen be- gan readying their bomb in a section of the camp controlled by the Hagana.

A large part of the job was preparing the gelignite explosive for smuggling onto the British prison ship. First, the gelignite had to be combined with an oily substance and kneaded. Then it had to be concealed for carrying aboard ship. The volunteers tried hiding it inside bars of soap, but this was unsatisfactory. The soap showed the marks of tampering where plugs had been cut from the bar. Shaving-cream tubes provided an answer. The shaving cream could be re- moved and the gelignite inserted, followed by a final portion of shaving cream to con- ceal the insertion.

The first stage of the Exodus affair was the occasion that triggered the bomb. On July 18, 1947, the British captured the American refugee vessel Exodus after a battle in which three Jews were killed and scores were in- jured. Instead of transporting her 4,515 pas- sengers to Cyprus, the British decided to send them back to Europe. This new policy became apparent within a few days, after the prison ships bearing the refugees failed to turn up at Cyprus.

On July 22, with the Exodus passengers on the high seas and heading for Port de Bouc, France, the prison ship Empire Life- guard was at Cyprus taking on immigrants for Palestine. Among the passengers board- ing the prison ship were American sailors from the Hatikva and a Palestinian leader with their unassembled bomb.

When the order was given to carry out the bombing, the effort invested in putting a final covering of shaving cream into the gelignite tubes proved its worth. A British soldier squeezed a tube to check its con- tents. Out came a dab of shaving cream, and the tube passed inspection. But substantial amounts of gelignite had to be carried onto the Empire Lifeguard in larger packages. A nurse escorting an infirm patient carried a package of about five pounds of explosive in her handbag and passed it to one of the American volunteer sailors as he boarded the ship. A British officer wanted to exam- ine the nurse’s package, but a superior of- ficer countermanded this decision. A more typical package was a rubber sack, strapped to the small of a man’s back and hidden be- neath his shirt. A number of such packages were brought aboard.

The interior of the prison ship consist- ed of large wire cages. The first American member of the bomb crew to board feared that the others would be shunted into sepa- rate compartments. He enlisted the help of women in his cage, pointing the Americans out to them. The women called out to the men, pretending that the Americans were their husbands, and the guards permitted them to enter together. When the group had assembled, an American handed a hacksaw to their Jewish commander from Palestine, who asked everyone in the cage to start singing.

As the passengers sang loudly, the Pales- tinian sawed the lock from a hatch cover in the floor of their cage. Opening the cover, he saw a light. He shut the hatch instantly and handed a knife to one of the Americans, instructing him to kill any sailor they found below. But when they descended into the hatch, it was empty. They assembled the bomb, minus its detonator, and returned to their cage for the overnight trip to Palestine.

Two hours before they were due in Haifa, the Palestinian inserted the detonator, which had its own timer to determine the precise moment at which the bomb would explode. All seemed in order. But, as the Empire Life- guard approached Haifa, the ship’s propeller stopped. Then, the anchor was lowered. The passengers trapped in the cage above the soon-to-explode bomb turned to the Pales- tinian. Wouldn’t it be a good idea to remove the detonator? He explained, “They taught me how to put it on. They didn’t tell me how to take it off.”

The prisoners thought about notifying the British that a bomb was aboard. But, if they did that, all chance of sinking the ship would be lost. After what seemed an eterni- ty, but was probably only about 10 minutes, the Empire Lifeguard pulled up her anchor and started moving. She entered Haifa harbor.

It was the morning of July 23, only five days after the British had brought the bat- tered Exodus into Haifa. As the Empire Lifeguard was unloading the last of its pas- sengers, a dull boom was heard and the ship shuddered. The passengers continued to file ashore. A British officer, remembering the nurse at Cyprus with the suspicious hand- bag, shouted, “That girl with the bag!” It was too late to save the prison ship. Slowly, the Empire Lifeguard sank to the bottom of Haifa harbor. The British never caught the bombers.

The bombing was remembered as the most successful attack on a British vessel during Aliya Bet. It was also costly. After the sinking of the Empire Lifeguard, the British imposed a monetary penalty on the Jewish Agency for transporting Aliya Bet passengers to Cyprus.

This article is adapted from a book titled ‘The Jews’ Secret Fleet’ by Joseph M. Hochstein and Murray Greenfield (Gefen Publishing House)

THE JERUSALEM REPORT SEPTEMBER 18, 2017