I was born in Pretoria in 1924. In 1940 at the age of 16 I was apprenticed to the Iscor Steel Works which was then manufacturing bombs, howitzers and mortar barrels. It was an essential war-material factory and it wasn’t easy to break my contract, but nevertheless I managed to do so, as I was determined to join the army. As I was under the age of consent, in 1944 I forged my mother’s signature and joined the Pretoria Regiment of Armored Cars in the South African Army. I was also a member of the Zionist Socialist Party and volunteered for the 1948 war since I wished to fight in a Jewish Army.

Tel Litwinsky was the absorption base camp for most Machal arrivals before they were posted to various units. Moshe Dayan was one of the commanders prowling around the tents and barracks of the camp, looking for tough men to join his commando battalion. He was assisted by Bert Fagin, a Londoner formerly of Britain’s 6th Airborne Division, and Paddy Cooper, a World War II veteran who had deserted the British and joined the Israeli side after witnessing the April massacre of medical staff on its way to the Hadassah Hospital on Mount Scopus.

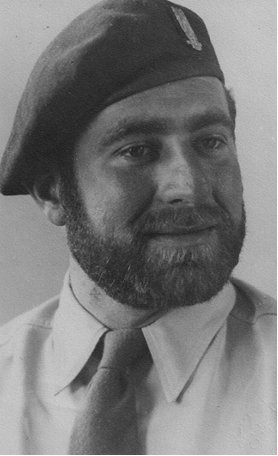

Fagin had already recruited Rhodesian Reg Sagar, ex-S.A.N.F. who had been a Japanese prisoner of war. Fagin also liked the look of a powerful young South African in a Rex Trueform suit.¹ “Care to join a long-range desert commando?” he asked me, “we’re training at Ben Shemen.” I jumped at the offer.

Another recruiter for the same unit was South Africa’s Jimmy Kantey. The Machal platoon filled up with more volunteers, not immediately, but over the following months.

The commando’s volunteers were tough men consisting of four groups: the Anglo-Saxons, ex-Stern group fighters, ex-Irgun and Palmach men. The ideological differences of the latter three were forgotten. Leading them was a young blond kibbutznik, a man of granite, Naphtali Arbel. Among the British were some non-Jews, sympathizers who had deserted the British Army to join us.

Left to right: Harry (non-Jew), Paddy Cooper (non-Jew), Bill Lehr (South Africa), Mike Isaacson (South Africa)

In addition to the original South Africans – Jimmy Kantey, Bill Lehr and Leslie Marcus, all three from Cape Town – there were others who joined us: Reg Sagar from Rhodesia, the non-Jewish deserters, Bert Fagin, a half-Jew and after the October “Operation Hiram,” a friend of Bert’s, and Mike (Jock) Klemitz who had transferred from the 72nd Infantry Battalion to our battalion. We also had Jochanan Sender who acted as our interpreter, a half-German Jew who had served in North Africa and later in the Jewish Brigade in Italy. He was a wonderful and fearless soldier. There was Abe, also a half-Jew, who had deserted from the American Occupation Army in Germany. The rest of the lads were from the U.K.

I had arrived in Israel towards the end of June 1948 and joined the 89th on 3rd July. In addition to our “B” Company we also had “A” Company, consisting mainly of ex-Irgun and Lehi men. All of us were ex-servicemen, so there was no need for training. It was just a matter of getting acquainted with the assortment of weapons, mainly from Czechoslovakia, the Mauser rifle, the Spandau light machine gun, and the Besa medium-size machine gun.

On 9th July our battalion formed up for action. Leaving camp at dawn we took cover in a deserted Arab orange grove. There we remained in our positions for the rest of the day, cleaning our machine guns and rifles over-and-over again. That night we moved cautiously towards Wilhelmina, only to find it deserted. Our next objectives were Tira and Kula where we met quite a bit of opposition from the Trans-Jordanian troops firing at us from the opposite hills. There was an exchange of fire for almost an hour, and we suffered a number of casualties. A volunteer from Britain was hit and called for help. Bert Fagin and I ran to his assistance, carrying a stretcher, but Fagin suddenly slumped. Blood oozed from a wound in his thigh. These two British were our first casualties. We then took Kula, leaving a couple of men to hold the position, and moved onto our next encounter, Beit Neballa, exchanging fire for the rest of the day and night with the enemy firing 25-pounder cannons. The following morning, after a sharp clash with Legion units, we captured the village, formerly a British camp. Then we moved on to Ben Shemen, raising the siege of the village which had been cut off for many months. Reg Sagar and I stared wide-eyed at the defenders, boys and girls aged 14 to 17, hand grenades in their belts, some carrying sten guns.

The battalion regrouped and went on to attack Lydda, but owing to an error at the crossroads by our platoon leader, Jimmy Kantey, we found ourselves in Ramle instead of on the road back to Ben Shemen with the others following. Moshe Dayan, the battalion Commanding Officer, recalled that the rest of us moved out, led by a captured Arab Legion armored vehicle with a turret and a two-pounder dubbed the “Terrible Tiger.” Following the “Tiger” came the halftrack and jeep company which encountered heavy enemy fire. The “Tiger” would halt from time-to-time, return accurate fire to the fortified position, and Arabs could be seen escaping from their positions which had been hit.

The visit to Ramle was brief, we were badly hit, there were dead and wounded, damaged vehicles and some missing men. Legion armored vehicles were now on their way to join the battle. Their unit in the police fortress, recovering from the surprise, manned its positions. The only withdrawal route ran right outside the fortress.

The order to retreat was given, the wounded were loaded onto the half-track, and the battalion prepared to return to Ben Shemen. As our halftrack with Paddy Cooper in command passed the fortress, following Jimmy Kantey’s in the lead, Kantey was severely wounded. Behind us was Jochanan Sender’s halftrack, then the rest of the unit with the Jeep Company backing us up with their heavy firepower. When we passed the fortress again we suffered a direct hit in the engine from a Piat shell. We jumped off, taking cover in a wadi. We had a number of casualties on our halftrack. After about 15 minutes, Charlie came back in his vehicle to pick us up. Another half-track with dead and wounded aboard had meanwhile passed us.

On returning to Ben Shemen, we carried the wounded into the dining hall which was being used as a hospital, and was now full of wounded and dying men. Kantey looked really bad and we didn’t expect him to pull through. The dead were lying outside, covered with blankets. I realized how real this war was. We had suffered casualties, but had inflicted tenfold on the enemy and had captured quite a number of armored cars and light artillery.

With the tide of battle going our way, operations decided to keep up the momentum. With only fitful sleep in two nights, we moved out of Ben Shemen, sleeping uneasily on the bumpy halftracks, and after some time we stopped at what seemed a large building. We learned that this was Lydda Airport, which had been captured by our 82nd tank unit.

Inside the airport grounds two jeeps blew up in a minefield. The tank crew thought that this was an Arab Legion counterattack and opened fire on our column. More men were lost before the mistake was realized. We reached the airport building at about 2 a.m. in the morning of 11th June. We slept off our weariness that night.

The men on the jeeps were fearless. We on the halftracks had some protection again small arms fire. Moshe Dayan rode in one of the jeeps leading the attack. Akiva Saar, our company commanding officer, was in the thick of the battle and in control of his men all the time. The men of the 89th were heroes. Paddy Cooper, an experienced veteran of the British Army in World War II, said that he had never served with braver men than those of the 89th.

At the end of October we were sent up to support “Operation Hiram” where Cooper, assisted by Bert Fagin and Leslie Marcus, successfully silenced a sniper from the village of Kfar Manda who had hit two of our men. In a troublesome village near Kibbutz Yochanan in the western Galilee, in a dawn raid with no opposition we found that all the residents had fled.

Following Reg Sagar’s instructions, I had a last look and found in one house a one-armed man, a boy and an old man, and took them to the officer-in-charge. On leaving, I took them back to their house, telling them to remain there and not to move.

During the October “Operation Yoav,” we were held in reserve to cover the central region in case the Arab Legion counterattacked in support of the Egyptians.

Towards the end of summer, in the mission to capture Beit Jubrin, fellow South African Leslie Marcus was cited for bravery for evacuating a wounded combat medic under intense Jordanian fire.

After numerous unsuccessful attempts with heavy casualties, the Iraq el Suweidan fortress, known as “The Monster on the Hill,” was finally captured on 9th November after a massive firepower attack with 75-mm guns firing at point blank, supported by mortars and medium machine guns. It was our group, the South African section led by Reg Sagar, who was the first to break into the fortress through the large hole in the wall caused by tank fire. Sagar was followed by me, “Bull” Bernstein, Bill Lehr, Leslie Marcus, Johnny Nakan, Ivan Sheinbaum, Harry Sher and Ralph Yodaiken. Close behind came the rest of the Machal platoon with Paddy Cooper turning a captured Vickers machine gun on the retreating Egyptians.

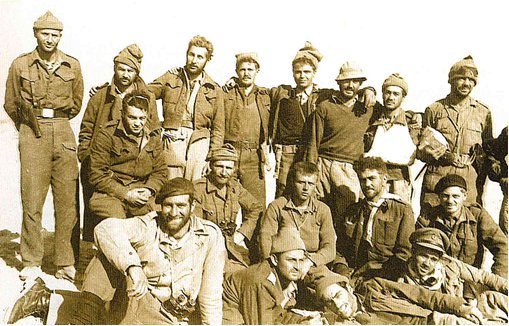

8th Brigade’s 89th Battalion following the capture of Auja el Hafir (Nitzana) in December 1948 ( (Mike Isaacson, front row left)

Next came the “Operations Horev” and “Ayin” from 22nd November 1948 to 7th January 1949. Our task was to capture the vital Auja-el-Hafir outpost. Our approach was via a recently uncovered and repaired old Roman road. A few days before the 25th, with Cooper on Christmas leave, I was in charge of his halftrack. Ralph Yodaiken was in command of the second one, with Jochanan on the third.

On the day before Christmas, a large force of Egyptian tanks attacked our company but fled when four were knocked out in as many minutes. I was having trouble with the starting mechanism of my vehicle but could not get it repaired as our mobile workshop had suffered a direct hit during an Egyptian Air Force attack. We needed a push to get our engine started.

On Christmas morning “A” company set oeut to make a direct assault on Auja-el-Hafir. The Egyptians succeeded in cutting them off, and they only managed to break out after suffering severe losses. Their commanding officer and his deputy were killed in this battle.

Our “B” company attacked a little later, with “the feeling of revenge” heightened by the sight of the burnt-out halftracks of “A” company. The Egyptians in the village opened fire. We made our assault in a “V” formation, firing rapidly. The Egyptian response was no less furious, some of its mortar fire knocking out several halftracks and killing Phil Balkin, an American volunteer. Some of “B” company’s vehicles were now stalled, others were retreating in the face of the heavy fire. Ivan Sheinbaum, a nineteen-year-old youngster from South Africa, was badly wounded, as were a few others in his halftrack. I shouted that ours was disabled, but my voice was not heard in the din of firing. I and my crew were now exposed to the shooting of an enemy troop taking cover in a wadi, some fifty yards away.

Then came the exploit of Rhodesian Reg Sagar for which he was cited for bravery. He had climbed out of his halftrack and with superb courage made his way towards the wadi, firing a 2-inch mortar. He knocked out the enemy positions with eight direct hits. The firing from the wadi stopped, but not from the village. Sagar was hit in the chest. My vehicle was also hit. Despite his wounds, Sagar ran towards Ralph Yodaiken’s forward halftrack, escaping the shots fired at him. With the assistance of Yodaiken’s vehicle, I got ours started and we made for cover where the rest of the company was regrouping for another attack. Our second assault was successful.

When we reached the wadi, we jumped off and charged into the village. We saw dozens of Egyptians lying where Sagar had blasted them. We captured the village without further incident, taking a large number of prisoners.

Our company was now poised to attack Gaza when the ceasefire came into effect, and we remained in the Negev for two months before returning to Ben Shemen. We were on standby for another month in expectation of more action in the triangle, but the operation was cancelled at the last moment. Our commando unit was finally disbanded to the disappointment of our sabra friends. We had served for nearly a year with the army.

I must record additional South African names of our unit not previously mentioned: Julian Shragenheim, Horace Milunsky, both veterans of World War II, and my cousin Arnold Isaacson.

I flew back to South Africa in mid-April 1949, on the same flight as the famous South African pilot Syd Cohen, and I had the privilege of seeing the farewell salute of the Spitfires of his 101 Fighter Squadron. On the same flight were other South African Machalniks returning to South Africa – Hymie Kurgan, Maurice Mendelowitz, Harold Sher, Leon Rosen, Joe Woolf and Julius Levine.

¹ A well-known South African clothing manufacturer

Source: Prepared by Joe Woolf from Mike Isaacson’s personal story, supplemented by excerpts from South Africa’s 800 by Henry Katzew.