It was a sight Frieda Macarov will never forget. “When David and I arrived in Jerusalem from Kibbutz Ginegar in October 1947, my love affair with the city began. The magnificent hills of Judea, the colors of the stones and the sunsets, the variety of neighborhoods, all combined to weave a tapestry of fascination for me. And to be quite honest, it was a real contrast with my childhood home in South Ozone Park, New Jersey.”

American born, 44-year-old Frieda, was a socialist devotee who trained to be a nurse at Bellevue Hospital in New York City. She was a cadet nurse at the close of World War II, but the fighting was over before she had a chance to serve. In the summer of 1946 she worked as a nurse at the Brandeis Camp in Hancock, New York, run by the noted educator Shlomo Bardin. There she met her husband-to-be, David Macarov.

A native of Georgia and a Zionist veteran who grew up in Young Judaea in Atlanta, David had served in the Weather Service in World War II. “While stationed in Calcutta, with its desperate poverty, I realized that working in a store or being a bookkeeper as I had done up until then, was not sufficient. I wanted to do more with my life.” David left the south following his discharge and moved to the north, signing up with the Aliyah Bet illegal immigration operations in New York. He laundered money, bought munitions to be smuggled to the Haganah and even signed checks for the purchase of seven ships which were ultimately used to bring refugees to Palestine.

“Living in Palestine, however, was always my goal. After Frieda and I were married in December 1946, and after her mother told her that a girl goes where her husband goes, it was only a few months later that, as part of the Masada garin, we made aliyah, settling at Kibbutz Ginegar.”

Although the Macarovs did not remain at the kibbutz, Frieda described an unforgettable part of that experience. “I worked in the potato fields at Ginegar, and I had this spiritual feeling that this is what my ancestors had done on this very soil. Without any Zionist background, my devotion to the country literally began through its soil in which I labored.”

After they moved to Jerusalem, David went to see Avraham Harman at the Jewish Agency, later an ambassador to the U.S, and president of the Hebrew University. He told Harman of his expertise in codes, ciphers and in signal security. A few days after the approval of the Partition Plan on 29th November 1947, David was secretly sworn into the Haganah. Taking the oath with him were a number of other Americans, all U.S. army veterans, who were enrolled at the Hebrew University. He was issued a weapon which was kept hidden most of the time. But, from time to time, he and several other Haganah members did guard duty at Neve Ya’acov. “For the 10 people on duty, we had three rifles and three grenades. We did the best we could.”

Frieda got a job as a nurse at the TB Hospital on Ethiopia Street. “On the one hand, conditions were not the best, and one could become infected. On the other hand, I did get to eat at the hospital, which was most beneficial during the siege. I remember that one day David and I were reduced to eating the vegetation you could pick in the fields. On a cold February 1948 day, we built a wood fire outside our building, Beit Harris on Hama’alot Street, using a log David had dragged home, and we boiled our greens on it.”

David especially remembered the reaction to the bombing of Ben Yehuda Street in February 1948. “We members of the Haganah boldly took out our ramshackle weapons and marched through the streets of Jerusalem. We showed that we could not be bullied or bowed by their threats and terrorist actions.”

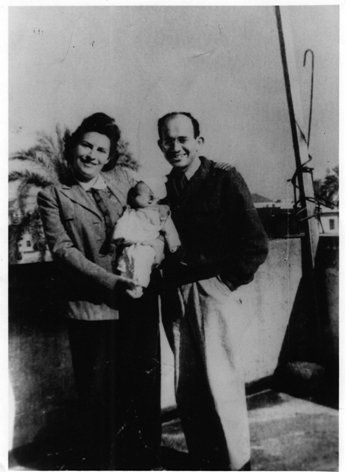

Although never officially in the Haganah, Frieda did her share. On several occasions she smuggled hand grenades into the main Jerusalem post office on Jaffa Road. She was also a lookout at the Putt Bakery – a Haganah post – at the corner of Rav Kook and Hanevi’im Streets. “With the ‘bees’ buzzing around our heads – our name for the sniper bullets – and with the shells falling constantly, who knew whether David or I would survive? Our child, a daughter, was conceived during the siege in the spring of 1948 and born in January 1949 in Jaffa, where David was then stationed.”

When an official from the American Consulate came to their apartment in March and asked them to leave, assuring safe passage out of the country, David’s answer was emphatically ‘no.’ Frieda added, “If he doesn’t leave, I don’t leave either.”

For Pessach of 1948, the Macarovs held the seder with Bea and Jerry Renov and their infant daughter, former Southerners from Atlanta and Shreveport, Louisiana, who also had made aliyah. “The convoys from the coast had gotten through,” David said, “and had brought a little extra food for the holiday. We had chicken and even some meat – quite a change in our diet.”

Once the state came into existence, David went into the IDF and was put in charge of signal security in Jerusalem. Later the Macarovs were ordered to Tel Aviv where David entered the air force and became a squadron leader. For a year he flew around the country checking security procedures at all the military installations. Following a stay in the U.S., the Macarovs returned to Israel, and for over 30 years, until his retirement, David was a professor at the School of Social Work at the Hebrew University. Frieda worked as a nurse, and for a number of years worked with Project Renewal.

Source: American Veterans of Israel Newsletter: Winter 1991