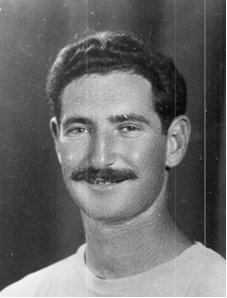

Jack Fleisch was born in South Africa on thee 12th April, 1924. At the age of 16 he joined the South African army in order to participate in the war against the Nazis in the 2nd World War. He was sent ‘up north’ to Egypt with the Cape Town Highlanders Regiment where they were stationed in Cairo. During that waiting period he visited Palestine as often as he could.

After Rommel was defeated at El Alamein, Jack was shipped to Italy with the South African troops to fight in the fierce campaign against the German army in 1944. He was seriously wounded during an artillery attack and was sent back to South Africa where he spent a year in hospital recuperating from his injuries. He suffered all his life from pain caused by innumerable pieces of shrapnel embedded in his body.

After the dramatic 29th November 1947 vote in the United Nations, Jack decided to throw his lot in with the nascent State of Israel by volunteering his services and military experience. He contacted several of his ex-army friends in South Africa, and together they formed part of the South African Machal group of volunteer soldiers during the War of Independence. Jack joined the “Chayot Hanegev,” an elite Palmach fighting unit, as a demolition expert with a vast amount of army experience. Their main thrust at that time was to block the advance of the Egyptian army on Tel Aviv.

The Iraq-el-Suweidan fortress, a strategically vital position overlooking Kibbutz Negba, had been handed over to the Arabs by the British army prior to their evacuation. This was contrary to agreements between the Israeli and British authorities whereby all the police stations would be transferred to the Israeli authorities when the State of Israel was declared on the 15th May 1948. Israeli control of the fortress was crucial to the campaign in the Negev in order to obstruct the advance of Egyptian forces on Tel Aviv. The Haganah mounted several attacks on the fortress and only succeeded in conquering it on the seventh attack.

The “Chayot Hanegev” special Palmach spearhead unit commanded by Israel Cohen manned one of these attacks on the 9th October 1948. Commander Israel Cohen relates that through a series of tragic failures in communication, Jack Fleisch and George Shelley ‒ a British soldier nicknamed ‘Sailor’ who had defected from the British army ‒ were separated from the other ‘Chayot Hanegev’ fighters who had meanwhile retreated. Jack and George Shelley were captured by Egyptian soldiers and were subsequently incarcerated in Abbassia prison camp in Egypt for 10 months.

EXCERPTS FROM “SOUTH AFRICA’S 800” ‒

The Story of South Africans in Israel’s War of Birth, by Henry Katzew

Chapter 2 (Part 3) – Jack Segal, an ex-radar officer in the South African army, had been approached by his cousin Jack Fleisch who told him that fighting was expected in Palestine and that trained personnel were desperately needed. Segal volunteered and before leaving was entrusted with a substantial check to be handed to the treasurer of the Jewish Agency. As he would be traveling ostensibly as an impecunious student, the check was wrapped in a condom and concealed in a tube of toothpaste.

Chapter 4 – For Lionel Hodes, Jack Fleisch and Horace Milunsky, the 14th May was a day on the roads. A few days earlier there had been two claimants for them, the army on the one hand and a representative of Kibbutz Ma’ayan Baruch on the other. The matter was argued out at the Tel Litwinsky camp between the camp commandant and a representative of the kibbutz. All three men, said the kibbutz representative, had had army combat experience in World War 11. Ma’ayan Baruch, less than a kilometer away from the Lebanese border, expected an attack on May 15th. It needed all the manpower it could get, immediately. In any case, the three had affiliations with their fellow South Africans on the kibbutz. A compromise was reached. The men would go to the settlement as military personnel for one month, at the end of which period the position would be reviewed.

The three set out for the Galilee on a crowded bus. Most of their fellow passengers were settlers returning to defend their homes. The British were still manning military points and would remain masters until midnight. British tanks and other equipment rolled towards the Haifa harbor.

At Afula, where the proposed Jewish state was to border the proposed Arab state, the South Africans changed buses, reaching Tiberias by way of a long detour. There, they and others transferred to an armored bus, for now the road would be dangerous. Rosh Pina, key Jewish town of the upper Galilee, lay through the hills and past the blue waters of the Sea of Galilee. The South Africans’ first view of the region was through the slits of the armor plating. Later, the doors were opened and the driver gave a running commentary of the history and scenes that lay before them.

At Rosh Pina the armored bus joined a large convoy led by armored cars. The signal was given and the convoy moved steadily into the “finger” of the Galilee. The British had given the fortress-like police station of Nebi Yusha to the Arabs who fired at the convoy. Doors slammed and shutters closed. The sharp impact of the bullets on the vehicle was the South Africans’ introduction to the war.

The bus stopped at a little outhouse, the driver opened the door facing away from Nebi Yusha, and three men quickly clambered in. They were members of Kibbutz Kfar Giladi, one of the oldest of the northern Galilee settlements. The men had been working at the fish pond belonging to the kibbutz, situated directly below Nebi Yusha. War or no war, the work had to continue.

In the distance, fires burned and the clatter of a small arms skirmish was clearly audible. The news quickly spread: “The Haganah was attacking a hostile Arab village.” The bus moved on.

Greeting the three men at Ma’ayan Baruch was done with little ceremony, for they arrived in the middle of an alarm exercise. The situation was explained to them briefly. Each village in the valley was expected to defend itself until the surrounding settlements could come to its aid. Kfar Szold, Dan and other settlements near Ma’ayan Baruch had already beaten off attacks. But now organized armies, not irregulars, would bear down on the settlements whose inter-communication would be maintained by radio, heliograph, lamps and flares.

The briefing showed the situation in harsh reality. By accepted military calculations, the kibbutz could offer little resistance to a determined assault.

Its arms amounted to about 25 weapons including one old two-inch mortar with a few shells, a Chateau light machine gun with several hundred rounds, and twenty or so smaller arms of diverse makes and age. The locally made Sten gun with a range of not more than 50 yards, vied for pride of place with a Tommy gun and an old shotgun usually used for hunting buck, as well as French, German, English and Czech rifles. Each weapon had its idiosyncrasies. An order had been issued by Yosef, the military commander, that ammunition was to be sparingly used, for nobody knew when the next lot would arrive.

The settlement had been well prepared for attack, both from the air and ground. Bunkers and shelters enabled the entire community to go underground, and even a small sick bay had been prepared in a shelter. The perimeter of the kibbutz was surrounded by several layers of barbed concertina wire, and mines had been laid. Shooting and observation posts ringed the camp and dugouts were linked to one another by wide communication trenches and telephone.

Due note had been taken of Arab superstition of the night. One thousand crackers, ready to explode when trampled upon, were strategically strewn around and phosphorescent figures were placed in position to serve as dummies.

The exercise over, all the settlers, except the sentries, gathered together for a party. Glasses clinked. The State had been proclaimed. What would come would come. The alarm went off accidentally, but apart from that, Kibbutz Ma’ayan Baruch slept peacefully on the night of 14th May.

Chapter 5 – Kibbutz Ma’ayan Baruch was part of the war zone throughout the month, but was spared the ordeal of it. The Syrians, it appeared, were not interested in the villages of the finger of the Galilee, but rather in the roads, which were frequently dive-bombed.

Jack Fleisch, Lionel Hodes and Horace Milunsky, concluding that Ma’ayan Baruch was safe, sought permission to leave the kibbutz in order to join a regular army unit. The kibbutz committee demurred, but the issue was settled by a new turn of events. The Syrians launched an attack on Kibbutz Mishmar Hayarden in the east, and from the west the Lebanese recaptured Malkiya. The Arab advance, it was immediately surmised, would be on the key settlement of Rosh Pina, gateway to the northern Galilee. Trained men were collected from every settlement in the region to meet the threat. Ma’ayan Baruch contributed the trio ‒ Fleisch, Hodes and Milunsky ‒ who were interested to find at Rosh Pina the flowing robed and kaffiy’ed Druze Arabs who had thrown in their lot with the Israelis.

Jack Fleisch, a demolition expert, was separated from Hodes and Milunsky. Captured a few months later in the Negev during an attack on the Iraq-el- Suedan fortress held by the Egyptians, he was taken to a POW camp where he suffered grim days that were to shatter his life.

Chapter 11 – On the 14th August, Paltiel Makleff, an Israeli pilot and Monty Goldberg, an air photographer from Johannesburg, crashed near Egyptian-held Beit Guvrin on their way home from a mission. They were saved from being lynched by the Bedouin tribes in the area by a lieutenant of the Transjordan Palestine police. They were later taken to a POW camp near Cairo.

At the camp Goldberg met fellow South African Jack Fleisch for the first time. Fleisch, it will be recalled, had been taken prisoner during an abortive attack on the Egyptian held Iraq-el-Suweidan fortress. He did not look good. The effects of poor diet and rough treatment that included beatings, torture and the mental torture of daily mock executions, were obvious.

Chapter 18 – Jack Fleisch never recovered from his incarceration by the Egyptians.

‘Abbassia’ is a poem written by Jack Fleisch during the time of his incarceration in the Egyptian prison camp of Abbassia in the 1948 Israeli War of Independence

ABBASSIA

Beyond the minarets and domes

That point their fingers to the skies

Beyond the teeming rush and hum

Of Arab Suks and beggars cries

As if a weary giant had dropped

His tangled load with careless hand

A barbed square throws its rusted lines

Upon the empty desert sand

They walk within its naked bounds

That clutch the earth and seem to hold

A fragment of another time

When jackboots tamped their dusty mold

But now the wires murmur of

A limbo later than those times

Of watchtowers manned by brown skinned men

Of lime brick-huts and dreary lines

Of burning sun and seething hate

When oaths and rifle butts descent

Upon the weary stumbling line

Of sweating cursing captive men

Of lives that pass in retrospect

At night, before their sleepless eyes

Those other times so long ago

That press from them some wistful sighs

But time plods on its weary way

The darkness moves toward the light

Another day of hopeful wait

And then again the empty night

Jack Fleisch

4/1/49 In Abbassia

IRAQ EL-SUWEIDAN FORTRESS – Background information:

Iraq-el-Suweidan was a Tegart model police station built by the British army during the time of the British Mandate in Palestine (1918 -1948). It was also known as the ‘Yoav Fortress’ named for Yitzchak Dubonov, the commander of Kibbutz Negba during the War of Independence. He was known by the epithet of ‘Yoav’ in the Haganah. The fortress controlled the main traffic artery to the Negev as well as the Majdal-Bet Jubrin road. It was evacuated by the British on the eve of Israel’s independence and on the same day, it was occupied by local Arabs. The first attack by the Haganah (Givati Brigade) on the 12th May 1948 was repelled by the Egyptian army that had in the meantime taken up position in the fortress during their invasion of the Negev. The fortress loomed above and harassed Kibbutz Negba by frequent artillery attacks. Many of the kibbutz defenders and Givati soldiers were killed and wounded during those attacks. The Givati Brigade launched several attacks on the fortress and one of Israel’s heroes, Gena Siman-Tov, was killed during one of them. Other attacks took place on the 19th May, 22nd May, 11th June, 9th July (the attack in which Jack Fleisch was taken prisoner), 19th October, and on the 20th October, when planes were used. One of the attacking Israeli Beaufighters was shot down and the three Machal crew members were killed. The fortress was conquered finally by Zahal during the eighth attack on the 9th November 1948.

TRANSLATED EXCERPTS FROM THE BOOK RESEARCHED

AND WRITTEN BY MILITARY HISTORIAN DANIEL NADAV

ISRAELI PRISONERS IN ARAB COUNTRIES DURING THE

WAR OF INDEPENDENCE

(Published by the Israeli Ministry of Defense)

Prisoner of War Camp – Abbassia, Egypt

The living conditions of the Israeli prisoners of war in Egypt, the first of whom were mainly from Kibbutz Nitzanim, improved considerably upon their arrival at the Abbassia camp situated in the eastern suburbs of Cairo. It must be mentioned that this relates only to the physical conditions and not to the manner in which the prisoners were treated by the guards which did not meet any accepted standards. The Abbassia Camp, established during the 2nd World War, was planned to accommodate high officers from the “Axis” armies and therefore was built according to relatively good standards. During the war it ‘housed’ mainly Italian prisoners-of-war. There were eight long main huts, each one having one large room where 15 prisoners were accommodated.

The officers amongst the Israeli prisoners were: Yochanan Manheim, Zvi Yardeni and Jack Fleisch, the sergeant major of the camp, who lived separately under better conditions. They were joined later by Paltiel Makleff and Monty Goldberg. The story of their capture is described in a separate chapter. These two air force men together with Jack Fleisch fulfilled leading roles amongst the prisoners.

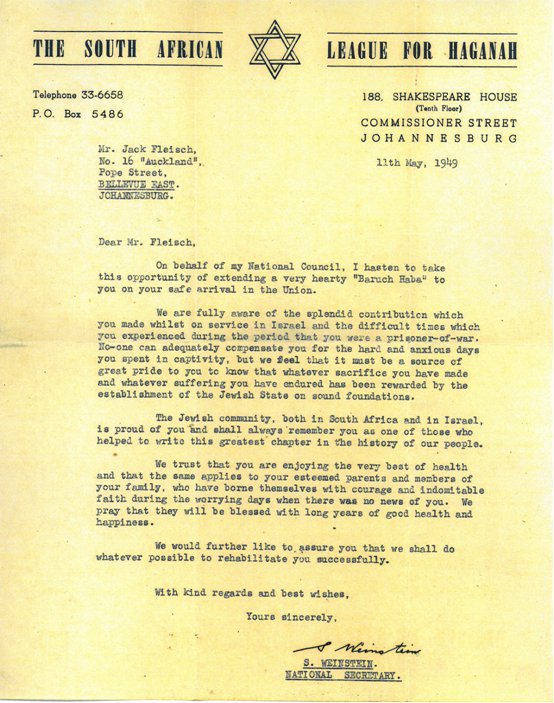

Israeli prisoners of war 1948 – Abbassia POW camp, Egypt

Jack Fleisch (standing, left)

The camp was surrounded by a double barbed-wire fence with numerous guard towers. The living quarters, toilets and washrooms were lit by electricity and there were seven showers with plentiful running water. When the Red Cross representative visited Abbassia in the middle of August, he praised the hygienic conditions in superlative terms. However, the small necessities like soap and toothbrushes were received from the Red Cross only at the end of August. In addition, the shortage of cigarettes and other items were keenly felt by the prisoners, and mail delivery from Israel was very slow. At the beginning the prisoners slept directly on the stone floor, but in the winter they were given thin mattresses.

The seven women and five Machal pilots ‒ Victor A. Weinberg (Holland), Albert Trop (U.S.A.), William Malpine (U.S.A.), Robert Fine (U.S.A.) and Hugh Curtiss (UK) ‒ were kept separately in huts that were built in the grounds of the Mazeh Prison in a suburb of Cairo, about one-and-a-half kilometers from the Abbasia camp. Despite the fact that they were in prison, their living conditions were better than those in Abbassia – they were even provided with mattresses immediately! Eight of the wounded remained for a period of time in the ‘Koba’ military hospital which was a small facility with only 20 beds and fairly reasonable sanitary conditions, but the medical treatment was on a very low level. Five of the eight had been very seriously wounded and the surgery performed on them was mostly unsuccessful. They were recognized as being severely disabled when they returned to Israel. In the Abbassia camp, all the lightly injured prisoners were treated by Dr. Perlmutter; however, there were great difficulties in attaining medical supplies.

At the beginning the food in the Abbassia camp was the same as that served in the Egyptian army and was supplied pre-cooked. The food was served in huge bowls every morning and afternoon with lentils as the main ingredient accompanied by pitot (dough bread) In the evening there was usually a fatty meat stew served together with rice and vegetables. The prisoners were very dissatisfied with the quality of the food ‒ at the beginning there was no cutlery at all. After the first visit by the Red Cross, the report noted that “no complaints were heard about the food.” It was later learned that the Red Cross representative had not allowed the prisoners to voice their complaints. Later, they were allowed to receive parcels from home. This also served to relieve the severe shortage of cigarettes.

At first the prisoners wore the tattered clothing in which they had been captured, but later they were issued with two sets of clothing: shirts, pants and other items from the Egyptian army. During the winter they received warmer clothing from Israel which was transferred by the Red Cross.

Paltiel Makleff, who was appointed Israeli commander of the camp, remembers the daily routine of the prisoners:

5:00 – Wakeup and morning exercises

5:30 – Morning wash and breakfast

6:30 – Cleaning living quarters and washrooms

8:00 – Parade, then work or studies

17:00 – Parade (in winter the afternoon parade was at 16:00)

18:00 – Supper

21:00 – Lights out

This seemingly civilized routine belies what really went on in the camp on a daily basis. The Egyptian commander of the camp, Colonel Anwar el Barodi, totally ignored all of the requests of the Israeli prisoners. The male nurse Nasif Larca made a mockery of his profession and abused his authority in a most cruel manner with the prisoners who suffered severely from his maltreatment. He was described as loving ‘baksheesh and hashish.’ Once, one of the prisoners lost his temper and a fist-fight developed between them. Nasif Larca quickly signaled to the guards who immediately surrounded the prisoners with their bayonetted rifles. The prisoner was thrown into solitary confinement and the rest of the men were punished with the hard Sisyphean task of carrying heavy rocks back and forth for several hours. This back-breaking work was repeated every morning for many days. During this period there were three visits by the Red Cross, but nothing was done to relieve the situation. The representatives were not allowed to meet with the prisoners without the presence of Egyptian officers, and therefore had no knowledge of these happenings.

The prisoners suffered a great deal of physical abuse that included beatings and whippings for the slightest infraction. The cruelest form of abuse was the ‘mock execution.’ Several prisoners were picked out for this special treatment whereby they were led to the firing range, blindfolded, told that they were to be executed and then reprieved at the last minute. Jack Fleisch was one of those who underwent this ordeal repeatedly, according to the testimony of Paltiel Makleff.

The prisoners constantly made plans of escape from the camp, but in the end there was a collective decision that the escape of one or two would bring down the wrath of the Egyptians on the rest of the group, and nobody knew where it would all end.

However, there was one unique case of a successful escape from Abbassiya which brought in its wake far-reaching effects. George Shelley was a non-Jewish fighter in the ranks of the Palmach “Chayot Hanegev” who was taken prisoner near Faluja during a failed attack on the Iraq-el-Suweidan police station, together with Jack Fleisch. He was a resourceful man, cheerful and sociable. During World War II he was stationed in Egypt and his British associates from those days remembered him well. George had contact with a tailor from Cairo who used to sew uniforms for the officers of the camp and through him he succeeded in smuggling letters to his friends in Cairo. He also arranged for the tailor to make him a new civilian suit and on the dark and foggy night of the 7th December he left a makeshift doll in his bed and escaped through the fence of the camp. According to Paltiel Makleff, a car was waiting for him outside, probably driven by one of his British acquaintances who then drove him to Cairo. After arranging false papers he hopped on a flight to Greece and from there he flew back to Israel where he reported to the military authorities. George Shelley’s testimony was recorded in detail in English and included descriptions of the abuse that he had undergone personally, beatings and various other humiliations, and the account of all the cruel treatment meted out to all the prisoners, in particular by Lieutenant Shukri, the sadistic ‘male-nurse’ Nasif Larca, the camp guards and others. This four-page document written in English, together with a Hebrew translation, is kept in the ‘Harel’ archives in Israel. He was sent to the Red Cross headquarters in Geneva where he delivered his testimony personally to the leading officials of the organization. There is no doubt that this was a most effective act that had a great influence on the officials and within a few days the leaders of the Red Cross decided to appoint a committee headed by the vice chairman together with De Rainier, head of the Israel Red Cross delegation. They flew to Cairo in order to examine the situation. The Egyptians were unable to ignore the delegation that went to Abbassia accompanied by high-ranking Egyptian army officers. The members of the delegation met with a representative group of prisoners and recorded their testimony. Paltiel Makleff directed the prisoners to speak truthfully and not exaggerate any of their experiences. The Red Cross representatives were allowed to interview the prisoners privately without any interference from the Egyptian authorities and the delegation was convinced that all the evidence heard was accurate. This visit resulted in an almost immediate improvement in the conditions and treatment of the prisoners. The harsh collective punishments imposed when George Shelley made his escape, were rescinded. The entire staff, including the commander and the guards, were removed from the prison camp and new men were brought in to replace them. They were tolerant and fair towards the prisoners and there was a certain improvement in the general conditions of the camp.

Sources: Written by Jack Fleisch’s sister Lydia Gosher, with adaptations by Machal chief researcher Joe Woolf

Henry Katzew’s “South Africa’s 800”

Israel Prisoners in Arab countries during the War of Independence by Daniel Nadav