Cecil Margo while serving in the Libyan Desert in 1943

Cecil Margo was born in Johannesburg in South Africa in 1915. During World War II he served in the South African Air Force, where he commanded 24 Squadron (medium bombers). As a bomber pilot he took part in more than 140 bombing sorties against enemy forces in North Africa and Italy, 99 of which were led by him. He achieved the rank of lieutenant colonel, and was awarded the D.S.O. and D.F.C. “He had completely devoted himself to his duty and his great ability had been the inspiration not only to all under his command, but also to all with whom he had come into contact.”¹

Cecil Margo receives the D.S.O. from King George VI in April 1947 at Voortrekkerhoogte during the royal visit to South Africa. Peter Townsend looks on.

The Israel Air Force had no formal birth. It was preceded by the Air Service of pre-state days, then by the air guerrilla outfit of the immediate weeks after the birth of the state itself. It is the South African claim that the IAF was truly born with the arrival from South Africa in July of Cecil Margo and Trevor Sussman. Sussman, deputy flight commander on bomber operations in the SAAF’s 24 Squadron, had served under Margo and was awarded the D.F.C.

David Ben-Gurion had heard of Margo through Bernard Gering, then chairman of the South African Zionist Federation, and had let it be known that Margo’s presence would be a great service.

The history of the air force before the arrival of Cecil Margo:

Seen retrospectively, the history of the air force before the arrival of Margo and Sussman was far from discouraging, despite the absence of organization. However, it must be repeated that none of the early arrivals from South Africa expected to find what they found here. Their previous experience was based on the sophistication of the SAAF in World War II. When the call went out for pilots, air gunners, radio operators and mechanics, the men naturally assumed that there would be planes to fly, guns to shoot, radios to operate and workshops with equipment. Syd Cohen got his first inkling of the real situation from his fellow pilots on the Messerschmitt course in Czechoslovakia. Boris Senior was the main storyteller, his accounts describing the hair-raising experiences of bomb-chucking, the workshop of sorts at the Tel Aviv airfield, and the nature of the airfield itself, with the wooden box that served as an observation tower. The men were still to learn more about the former RAF base at Ekron (Akir), established by the Israelis as the terminal for supply flights of the C-46s from Czechoslovakia. The essential fact was that Alex Zielony, the Israeli appointed O.C. of the field, had served in the RAF but lacked the necessary experience to be in command of a base.

An organizational structure of a kind came into existence after May 14th at headquarters in Tel Aviv. Dan Tolkowsky, although ex-RAF, but too freshly enlisted for operational experience in World War II, was appointed Chief of Air Operations. Smoky Simon became his deputy. Boris Senior’s appointment as O.C. of the Tel Aviv airfield was made official. Some weeks later Dov Judah became Director of Operations.

In anticipation of the arrival late in May of the first Messerschmitts, Modi Alon, an ex-RAF Israeli, was appointed commanding officer of the fighter squadron. Alon, born in the Galilean heights of Safed, was an extraordinary young man: he commanded by character. Veterans of the Pacific War, of North Africa, Britain, and Europe, seasoned fliers of P-51 Mustangs, P-47 Thunderbolts and Corsairs, may have resented, even scoffed at a commander whose log book was that of a beginner, albeit a promising one. Yet the secret signs by which men recognize a born leader were read by all. Alon’s authority was accepted. He won respect by his very presence. “If he dressed us down,” said Syd Cohen, “we really felt it.”

The most celebrated aerial event of the first weeks of the war was Alon’s downing on June 3rd of two Egyptian Dakota bombers over Tel Aviv. Surprised by the sudden appearance of the Messerschmitt, the Dakotas tried to flee, but Alon made swift work of them. One crashed over Bat Yam, near Tel Aviv, while the second was intercepted while trying to head south. It tumbled to its destruction over Rishon-le-Zion. Modi Alon’s success became the talk of the country that so desperately needed an air victory such as his. From that day the Dakota raids over Tel Aviv – though not the Spitfire raids – became fewer, though they did not entirely cease.

Syd Cohen’s overriding impression was the quality of his Israeli fellow pilots. Modi Alon had the qualities of an “ace.” Ezer Weizman, though without operational experience, had already demonstrated that he was a born airman.

Shortly before Alon downed the Egyptian Dakotas on May 29th in the first sortie of the Israel Air Force, a flight of the first four newly arrived and re-assembled Czech-built Messerschmitts (Avia S-199s) scored another success. They strafed the Egyptian column at Ashdod bridge, and this attack effectively stopped the Egyptian advance towards Tel Aviv. However, accurate anti-aircraft fire shot down one of the S-199s and the South African pilot Eddie Cohen was killed.

Another success before Margo’s arrival was the bombing of Cairo and other Egyptian targets by the three newly-acquired B-17 Flying Fortress bombers which were flown to Israel from Czechoslovakia.

By June 11th when the fighting ceased for the first truce, the twenty-seven-day- old Air Force could look back on helping to halt the Egyptian advance on Tel Aviv, the downing of two Spitfires and two Dakotas, the raid on King Abdullah’s palace in Amman, the strike against three Egyptian ships approaching the city, as well as a raid on Damascus. For a country a month old and starting from scratch, it was a creditable achievement.

Cecil Margo’s arrival in Israel:

Margo and Sussman left Palmietfontein in mid-July, reaching Rome via Tunis. In Italy they spent some time at the Haganah’s flying school at Urbe, and then flew by Aero Czechoslovakia to Haifa via Athens.

The next day they were ushered past girl soldiers armed with sub-machine guns into Prime Minister Ben-Gurion’s home in Tel Aviv. Margo , tall, self-possessed, confident and knowledgeable, made an immediate impression on the premier. Sussman, a youngster in his early twenties, had a sense of the strangeness of events which had placed him in the presence of Jewry’s most formidable personality.

David Ben-Gurion, never one for small talk, got down to business immediately. He did not know much about an air force, but an enforced stay in London when the Luftwaffe was raining its bombs nightly on that city, when he had taken refuge in air raid shelters, reading up on the great military men of history and their battles, had left an abiding influence on him. The Battle of Britain, of which he had become an involuntary personal eyewitness, left him profoundly contemplative. Watching those scenes enabled him to see into the future. It filled him with a vision of a Jewish Air Force as courageous and gutsy as the RAF in those supreme days of British destiny. When he was finally able to leave the battered but proud British metropolis, he carried with him a profound regard for the quality of these brave men and their professionalism.

In fact, many experienced aircrew volunteers from World War II often compared the atmosphere and spirit of the Israel Air Force in 1948 to that seen in the Battle of Britain period. It was almost like the play of natural forces that Ben-Gurion and Margo should now be closeted together in Israel’s hour of destiny.

“I give you an open directive,” Ben-Gurion said to Margo. “Learn what you can, see what you want to see, talk to whomsoever you wish, and let me have your recommendations.”

The immediate day-to-day routine for Margo and Sussman became one of inspection and inquiry. Inspection at the airfields confirmed how thorough the destruction of usable equipment by the British had been. Their probe involved consultations and talks with Aharon Remez, Boris Senior, Dov Judah, Smoky Simon, American volunteers, South African fighter and bomber-pilots, and others in a position to broaden their insights.

Margo could not but be concerned with the want of organization. IAF HQ in Hayarkon Street was a shambles. No effective chain of command or administration existed. The army directed air operations without the participation of Air Force HQ; air intelligence was conducted in a neglected room in a basement; flight training was in the hands of “Pappy” Green, a seasoned U.S.A.F. officer with every possible qualification, but with little or no help from HQ; ground training of pilots was left to a former U.S.A.F. colonel who was not Jewish, with no attempt at liaison or supervision from headquarters; maintenance of aircraft was organized ad hoc by Danny Shimshoni, with little support from headquarters or the air force stations themselves; procurement of the few obsolete but vitally important B-17s had been left to Al Schwimmer, who fortunately had coped with this assignment.

Within days Margo introduced changes. He confirmed Aharon Remez as A.O.C., and he appointed Dov Judah, who had served under him in Italy, Director of Operations, and Smoky Simon Chief of Air Operations.

Margo threw himself into the problems of personnel, equipment, aerodromes, armament, maintenance, training, operations, logistics, staff structure, telecommunications, air intelligence and, toughest of all, an air force budget.

He sought strenuously to pry away direct operational control from the army, but in this he was not successful. It is probable that this was the reason that he had declined the initial invitation by Ben-Gurion to command the IAF, and because he felt that in the prevailing environment at that time, air force/military considerations would be frustrated by political considerations, and that he would not have the authority which he felt was mandatory for doing the job.

His establishment and operations plan was completed in 10 days. Its objective was the rapid establishment of a relatively small fighter-bomber force, trained and operational as a multi-purpose air force in which every pilot would be qualified for instrument and night flying under the most exacting weather conditions, and which would be served by a system of alternate airfields, with abundant coded navigation aids, and underground revetments for the protection of aircraft.

The basic operational aircraft were to be front-line fighters, but adapted to take quick-change variations of armament and equipment. For fighter interception of enemy aircraft, they would be equipped in front with heavy-caliber machine guns and 20mm or even 30mm machine cannon; for medium bomber attacks they would carry external wing and belly racks, 4 x 250lb bombs, plus rockets on under-wing rails; and for any variations of bomb loads or rockets, the appropriate racks and rails could be fitted within minutes on the ground. These aircraft would achieve the necessary versatility by being altered by ground crews to carry the requisite armament, ammunition and fuel tanks, and this could be done rapidly and on short notice. The same aircraft would thus provide home defense, medium-range bombing, ground attack and close army support, anti-tank attacks with armor-piercing rockets, anti-shipping strikes, and long-range reconnaissance. Moreover, they would be operational in weather conditions in which all but the most sophisticated air forces would be grounded. Margo believed that suitable types of aircraft were available from Italy, France, and Belgium. The production of ammunition, bombs and rockets in Israel was no problem.

The plan also called for a maintenance system based on the then new concept which was coming to be accepted by airlines, maximum utilization of aircraft; thus, instead of an aircraft being withdrawn from service entirely while major maintenance was being carried out, such maintenance would be done bit by bit in the course of daily inspections. Instead of engine maintenance being done with the engine in the aircraft, the engine would be changed so that the aircraft would remain operational while the time-expired engine was once again made serviceable in the workshops. This concept has long since become standard procedure all over the world, but at the time it was novel, especially in air force thinking. The plan to have one main type of combat aircraft had the additional advantage of standardizing maintenance, equipment, and spares.

Margo included a major extension of the early warning radar system in his plan, which would give advance notice of the approach of enemy aircraft and the return of the Israeli planes. At that stage Israeli radar was operating with makeshift equipment improvised with great ingenuity by a low profile radar unit, 505 Squadron, which included a significant number of South African volunteers. Margo also made provision for the heavy training programs which would be required, and for the establishment of a proper air staff, with due regard to strategic planning and air intelligence.

Ben-Gurion accepted Margo’s plan in principle, but it got hopelessly bogged down in problems of finance and procurement. There were too many priorities in the minds of members of the cabinet and the army’s basic needs obviously came first. As Margo saw the position, it would be a long time before the IAF could be anything more than a third line formation used by the army on an ad hoc basis from time to time. Discouraged, and with the feeling that he could contribute little more, Margo decided to return home to South Africa. Sussman returned with him.

On the eve of their departure towards the end of August, the air force threw them a party; those present included the newly-appointed heads of departments, with Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett the guest of honor. The party did not warm up immediately. However, clinking glasses helped make the atmosphere more cordial. The inhibitions created by the different origins and background of the men dissipated in the flow of alcohol. Volunteers from abroad who joined the party were Trevor Sussman, Dov Judah, Americans Dov Kinarti, Danny Shimshoni, Al Schwimmer and Nat Cohen, and Israelis Aharon Remez (AOC), Heyman Shamir (Deputy AOC), Goladi, Rutenberg and Yacov Frank.

As the evening wore on, a comradeship was born, with the help of Moshe Sharett as raconteur. He recalled his experiences as an officer in the Turkish Army in World War I and sang Turkish army songs. When the party finally ended, Margo laid his hands on Judah’s shoulders: “Dov,” he said, “whatever happens, attack, attack, attack!” The instruction was to become the incantation of the IAF, the psychological property of every O.C. and every airman.

Back in South Africa, Margo and Sussman organized the selection and training by a commercial flying school in Germiston of pilot trainees. Of 14 trainees who completed the courses, Solly Kramer, Gerald Kaplan, Nathan Friedman, Reuben Narunsky, Leslie Lazarus, Hymie Schachman and Harry Caganoff left for Israel in January 1949, followed in July 1950 by George Katz, Len Lewis, Basil Sanders, Sam Levinson, Max Sher, Morris Sidlin, and Reuben Sher.

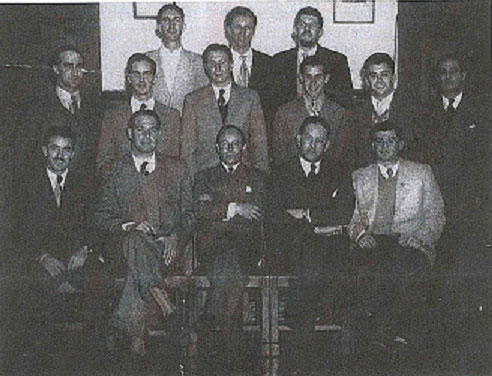

Organizers and graduates of the Advanced Pilots training course in South Africa, July 1948.

Left to right, back row: Reuben Sher, Reuben Narunsky, Morris Sidlin

Middle row: Simie Weinstein, Max Sher, Solly Kramer, Len Lewis, Nathan Freidman, Trevor Sussman

Front: Basil Sanders, Cecil Margo, Bernard Gering, Leo Kowarsky, Sam Levinson

When Commercial Air Services set up the program for training pilots in South Africa for the Israel Air Force, Cecil served as a consultant in formulating and monitoring the training program. He was also instrumental in acquiring equipment for the training course from the South African Air Force. He enjoyed an excellent personal relationship with Field Marshall Jan Smuts, the previous prime minister of South Africa.

It was left to others to equip the IAF and to build and train it into the immensely prestigious and efficient war machine it is today. Margo stands in the record as a frustrated visionary, a man a few years before his time in the infant state. When Ben-Gurion visited South Africa in 1969, one of the first men after whom he enquired and whom he wanted to meet was Cecil Margo, an acknowledgement of the debt the IAF owed to this South African.

Cecil Margo practiced as a lawyer for many years, and in 1971 he was appointed as a judge of the Transvaal Division of the South African Supreme Court. He passed away in 2000.

¹Quoted from the official citation.

Source: “South Africa’s 800” by Henry Katzew, and the late Eddie Kaplansky.

Sources: “South Africa’s 800” by Henry Katzew.

The late Eddy Kaplansky, former Machal pilot from Canada.