Click here to view Parts I-III

Part IV: Writing in My Father’s Footsteps

The Men of Company B and the Taking of Tamra

Prior to the arrival of my father and the first wave of Machalniks in May 1948, the fledgling Israeli army had taken huge losses. These losses weren’t simply because the soldiers were heavily outnumbered, but because the Israeli army had not yet become a unit: It was still a disorganized patchwork quilt of antagonistic freedom fighters (including the Irgun, led by Menachem Begin — the group responsible for the rescue of political prisoners from the British prison in Acre a year earlier), World War II vets and concentration camp survivors, all waiting for weapons and equipment to bypass the blockade.

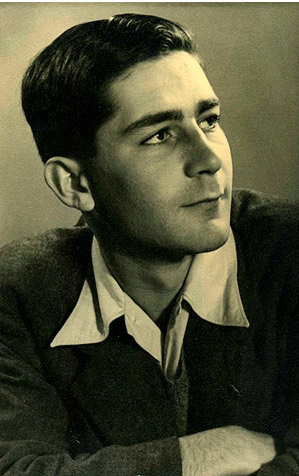

COURTESY OF NORMAN SCHUTZMAN

Your Country Is Safe With Us!: Officers of the 72nd Battalion including (far right) Norm Schutzman and (far left) David Apple, a non-Jewish British soldier who trained the first paratrooper battalion in Israel.

One Machalnik put it bluntly:

“Had I arrived on May 18 as originally intended, I would have probably died from some slip-up in battle, maybe friendly fire… let me give you an illustration: An Egyptian warship came to Tel Aviv. They thought it might land troops, so they sent out a Tiger Moth; that was the little two-seater plane they’d gotten. They of course threw down bombs on the Egyptian warship, which went away. But the bombs blew up their own Tiger Moth, and they both died… that sort of shock, disorganization and inability to respond was characteristic to those days.”

The most famous and tragic example of this lack of organization involved what was to become my father’s battalion — the 72nd Infantry Battalion, 7th Brigade — at the Battle of Latrun.

In May 1948, even under the partition, Jerusalem was an international city inside the Arab state, but because the Old City consisted of both Arab and Jewish residents, it was defended by the Haganah. Jerusalem was attacked and captured by a Jordanian legion, but the Israeli army intervened before they could capture the New City. East Jerusalem was besieged, and the only way to bring food, water and other supplies into Jerusalem was via a road that ran through the Arab village of Latrun. The British decided to defend this road to Jerusalem in Latrun with a Tegart fortress — essentially a large, well-fortified building with a dual purpose: to jail captured Jewish soldiers and to prevent access to Jerusalem.

This put the Israeli army in a very difficult position: Either break through at Latrun to end the siege, or just let Jerusalem go. Stretched thin, and on the defensive — especially on the Egyptian front in the South — the Israeli army was nevertheless determined not to abandon Jerusalem. As there weren’t enough troops to take on the Jordanian legion entrenched in Latrun, a decision was made to use Holocaust survivors, also known as Displaced Persons (DPs), who had recently arrived, give them a day’s training, put them in civilian buses boarded on the front in order to withstand machine-gun fire and drive them up to Latrun for a full-fledged attack. The attack ended disastrously as the DPs were mown down by machine guns the British had provided to the Jordanian soldiers, and the battalion was decimated.

In a bitter irony, after five failed attacks, some soldiers discovered a goat path that bypassed Latrun. That path, which became known as the Burma Road, would in turn save Jerusalem.

A Machalnik who arrived a few weeks before my father told me that the events at Latrun inspired new Hebrew words to a Russian song:

I’m not afraid of the Acre jail,

Acre is also the Land of Israel.

If tomorrow they exile me to Latrun,

Even Latrun is the Land of Israel.

It wasn’t until around July 1948 that a degree of stability, organization and training began to take hold in the Israeli army. This was due, in part, to the infusion of new equipment and the first wave of Jewish volunteers from around the world, like my father. In May 1948, three weeks prior to my father’s arrival, Norman Schutzman, his soon-to-be commanding officer, landed in a plane that had taken off from Greece. Schutzman told me that when he first saw the bay at Haifa, and Mount Carmel rising behind it, “there were no words I could find to describe how I felt. I was coming to the land that was promised by God to my people 3,500 years ago.”

Schutzman had come to operate and train others to use anti-aircraft guns but they had not yet arrived from Czechoslovakia, and there was no information as to when they would. Schutzman was given a choice: Wait around for the guns to come, or join the infantry. Schutzman found this “a silly question,” so he was officially inducted into the Israeli army as an infantry captain and ordered to report to the demoralized 72nd Infantry Battalion, now stationed north of Haifa. On his first day in the army, Schutzman met the battalion commander, Jack Lichtenstein, an American who had made aliyah years earlier. Lichtenstein had just received orders from brigade headquarters; the 79th Tank Battalion was planning to attack Nazareth, the largest Arab town in the Galilee.

Lichtenstein, along with his companies, was ordered to dig in east of Nazareth to stop a potential counterattack. He assigned Schutzman to lead the English-speaking Company B of the 72nd. Schutzman received a shock when his new company lined up before him; presented with only 60 men, his sum total of arms numbered 13 rifles, a few pistols and a handful of grenades. Luckily, the ill-equipped and undermanned 72nd avoided any losses as the 79th Tank Battalion took Nazareth that night without a shot being fired.

After his arrival from Marseilles two weeks later, my father was processed at Tel Letvinsky and was driven 20 miles to where he met Schutzman and the rest of Company B. On the 1948–1949 roster for Schutzman’s Company B was a motley crew of 118 men from nine countries. Nearly half were from the United Kingdom, with significant numbers from the United States, South Africa and Canada; perhaps more surprising were the representatives from Kenya and India, Costa Rica, Holland and Norway. However motley, the men of Company B were united in elation a week later, when crates of rifles and two machine guns arrived from Czechoslovakia. Not only was the battalion now at full strength, but for the first time, each man had a weapon.

The other companies of the 72nd Infantry Brigade were organized by language: Company A comprised Polish Jews who did not speak English, Company D comprised French-speaking Moroccans and Company C comprised Yiddish, Polish and Russian speakers who were, ironically, anti-Haganah, and anti-Ben-Gurion.

“Their anger at Ben-Gurion stemmed from the story of the Altalena, an Irgun ship on which the men of Company C were sent into the country along with smuggled armaments. Originally, the Altalena was supposed to dock mid-May, but instead it arrived mid-June. While the Altalena had been sailing toward Palestine, a month-long truce had been called for June. Menachem Begin took the view that, since the Arab and Israeli forces had been violating the truce, the Irgun would bring the ship into Israel surreptitiously. Ben-Gurion, however, as commander-in-chief of the truce-abiding army of the state of Israel, ordered it sunk. When the men on the Altalena finally got off the boat, they were enraged at the Israeli army for shooting at them. A Machalnik told me that the men of Company C would march and sing the following in Russian all day long:

Ben-Gurion’a

Altalena

Ben-Gurion’a

Altalena

Ben-Gurion’a

Altalena

Yob tvoyoo mat’! (“Motherf—-r!”)

For the next few months, Schutzman put my father and his company, with the help of two Sabra platoon commanders, through the normal training program of an infantry company. One of those Sabra commanders, Ayah Peled, would become a friend and confidant to Schutzman, and in a few months, he would be a tragic figure.

In September 1948, during another U.N.-imposed truce between the Arabs and Jews, an extremist Arab group was using the large hill at Tamra to fire on Jews: Schutzman was given the order to capture it. On September 6 — the day he received his orders — Schutzman drove to the hill with his platoon commanders to set up a battle plan. He returned later that night with my father and the rest of Company B, in buses that let the men out a mile from the hill. Schutzman’s plan was for his company to climb slowly up the hill in the cover of night, with one platoon in reserve behind them. Company B proceeded to make its way toward the top and dig in. At daybreak, on September 7, the men of Company B began to take mortar fire from the Arab forces above. The mortar fire soon became increasingly heavy, raining down on my father and on Schutzman’s men. Schutzman called for the reserve platoon to come up. The platoon commander below had ordered his men to fix bayonets to their weapons, and the platoon, with only three deaths, swept through the Arab forces on the hilltop, taking the hill by dawn. This bloody charge was the only bayonet fight in Israel’s entire history.

BASED ON UN MAP OF THE ARMISTICE LINES OF 1949, NO 547, 10/1/53

Divisions, divisions: UN maps show the narrow corridor between Tel Aviv, Latrun and Jerusalem.

By the time I knew my father, it was common knowledge in the family that he had a strange fear of his children’s blood; he’d often pass out when he would see us bleed. No one knew why he had this reaction, but it now seems linked to that intensely bloody morning on the hill at Tamra. Schutzman recalls the effect of Tamra on one of his men, an 18-year-old with no prior military experience who, like my father, was from New York. Throughout training, this young man would constantly boast to everyone around, “I can’t wait to get myself an Arab.” That morning at Tamra, after the first shots rang out, this same young soldier fled straight back down the hill. The trauma of battle left the young man with severe psychological problems, and two months later he was sent back home.

The day after taking Tamra, Schutzman recalled reading a newspaper; on the front page, there was a small paragraph that stated there had been an “engagement” at Tamra and that the Jewish army now controlled the hill. Schutzman said, “Since then, whenever I read in a paper or a book about any action, battle or accident, I can appreciate the difference between reading about it and being there.” Schutzman’s observation had a profound effect on me. Here I am, attempting to put myself in the shoes of my father, a man I love and miss deeply. And as much research as I do, or as many of his peers as I speak to, I will never truly know what he felt and experienced as he and his company continued on to their next “engagement.”

Part V: Writing in My Father’s Footsteps

At Mount Meron, His Final Battle

After the battle at Tamra, my father’s commander, Norm Schutzman, moved the men of B-Company up to the coast North of Haifa for more training. In late fall, Schutzman received orders that the entire 7th Brigade, including his company, was to clear the Galilee of Arab troops to the Lebanese border.

Schutzman’s company’s assignment was to take Mount Meron, the highest mountain peak in Israel. Arriving in Safed, Schutzman went to Meron with a platoon commander to devise a strategy. It quickly became clear that his men would have to gain control of the tomb of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, which is situated on Mount Meron and had acted as a military fortress for Arab troops.

Back in Safed, Jack Lichtenstein, commander of the 72nd Battalion, briefed Schutzman: A guide would lead his company behind enemy lines at night for a daylight raid of Shimon’s tomb. That same afternoon, however, orders came from David Ben-Gurion that the operation was to be canceled; Count Folke Bernadotte, a Swedish diplomat, and the United Nations mediator in Palestine, had been assassinated by Lehi, an extreme right-wing Jewish group. Ben-Gurion felt that, from a diplomatic standpoint, the timing of the attack would be wrong. For weeks, Schutzman and his men waited idly.

Six weeks later, Schutzman received the order to take Mount Meron. To sneak behind enemy lines, Company B left Safed at nightfall, and met the guide who took them into the fields. Marvin Libow, a soldier who fought alongside my father, recalled, “We got out of the buses and it was pitch black. You couldn’t see your hand in front of your face.” Schutzman recalls that the guide took them across a bridge leading to the base of the steep climb up toward Shimon’s tomb. The plan was to blow the bridge to prevent any counterattack, and sure enough, a half-hour later, around 1 a.m., the bridge was blown.

COLLECTION OF NORM SCHUTZMAN

Shiva for Ayah: Lt. Ayah Feldman was killed on a hill overlooking Lebanon.

Reacting to the explosion, Arab forces at the tomb began to fire Very pistols

into the sky to see what was happening on the hill below. The flares lit up the landscape, showing Schutzman and his men that their guide had actually gotten them lost; they were on the wrong side of the mountain! By the light of the magnesium sky, they were able to reposition themselves to attack at daybreak.

At dawn, the attack began. The ascent to Shimon’s grave was steep, with no leaf cover and strewn with rocks. The tomb was a concrete fortress, and Schutzman recalled that the only way in would be to focus their artillery on a few vulnerable windows. Libow remembers that during the fight, one man, Shmuel Daks, was killed. Daks was an Austrian-born Englishman who was fighting alongside Libow. He couldn’t get a good shot, so he rose from his crouched position to get a better view. Libow remembers hearing the sound of Daks’s weapon jamming, then a burst of machine gun fire from the Arabs above, in the fortress.

The next moment, Libow was digging rock fragments out of his face, calling out, “Daks, are you all right?” Libow, finally able to see, saw that Daks had stopped breathing. Not knowing what to do, he ran over to his sergeant, Jack Franses. Libow yelled, “Jack, Jack! Daks is dead!” Franses snapped back at Libow, “Shut your f***ing mouth!” Libow, green in battle, didn’t understand that the loss of morale created by word of casualties could be deadly.

Schutzman and his men, including my father, finally took the tomb. It took the rest of the 72nd Battalion two to three days to sweep the rest of the Galilee. From Meron, Company B went through Jish and Sasa, and from there north to the Lebanese Border. The next day, they spread out on a hill overlooking Lebanon. Schutzman remembers that they could have easily swept through all of Lebanon, but Ben-Gurion made it clear that his men were to stop at the border. After instructing his platoon commanders where they should place their men, Schutzman was visited by his friend Lieutenant Ayah Feldman at company headquarters.

Feldman wanted to show Schutzman something special: Away from the platoon, on the other side of the mountain, was an incredible view of Lebanon. Schutzman recalls that after the two friends crossed a ridge, Feldman ran forward and crouched down behind a large rock. Schutzman followed and crouched down next to him, pulling out his maps to see where they were. As the two took in the beautiful vista, Schutzman recalled suddenly hearing shots ring out. He looked to his left to find that Ayah, his friend and confidant, was dead.

As Schutzman turned his attention, he saw a swarm of Arab troops coming directly toward him. Schutzman began to scream for help, but knew he was too far from his men for anyone to hear: “I knew this was the end. People say that every soldier in a foxhole prays to God. I am not a very religious person. It never occurred to me to pray to God. I grabbed Ayah’s pistol and my own pistol and started to fire. My only thought was that my mother wouldn’t recognize me. A few weeks earlier, a scout of mine had been completely mutilated by an Arab.”

As the Arab troops descended on Schutzman, he heard some yelling, and looked behind to see his company coming up over the ridge to his defense. After some fighting, his men were able to save Schutzman and to recover Feldman’s body. At the time, Feldman was engaged to be married.

Later, wracked with sorrow, Schutzman went to visit Feldman’s parents while they were sitting shiva. Feldman’s father was president of the Palestine Electric Company at the time, and Schutzman recalls him crying: “Dear God, why didn’t you take me? I’ve had a life and Ayah’s life was all before him.” Schutzman said: “It often crosses my mind — if I had flopped to the left of Ayah, rather than the right, Ayah would have a wife, children and possibly even grandchildren that would be his pride and joy. I would be the one lying in a grave on Foulk Road.”

It wasn’t until 1998 that Schutzman discovered how his life was saved. Irv Matlow, from Toronto, wrote to Schutzman to verify his account of his war experiences. Matlow had been assigned to Company B as a signalman while they swept the Galilee. While Schutzman and Feldman were being attacked, Matlow had received a call from Jack Lichtenstein, who wanted to speak to Schutzman. Not able to find Schutzman, Matlow went looking for him, saw the advancing Arab troops and radioed back to the men of Company B to come to his aid.

Since Schutzman discovered that Matlow had saved his life, the two have become close friends, and they and their wives meet every year at Niagara-on-the-Lake.

Meron was the final battle my father fought in before the 1949 armistices were signed. My father stayed in Israel for four more years, living on the newly formed Moshav HaBonim, which still exists just south of Haifa. My mother recalls that my father told her the moshav comprised South African, English and American Jews, and that for four years, my father worked as a tractor driver and took care of the cows. Eventually, my father returned to the States. A staunch Zionist, but not religious, he felt that it was time for him to make a break with his Orthodox family, and he made a trek to California, where he eventually married my mother, had four children and spent 30 years working for IBM.

My father passed away at the age of 66, when I was 18. For those 18 years I loved him more than anyone in the world. Being a father at a late age made him gentler than he had been with my older brothers and sisters. Instead of teaching me about sports, he taught me the joy of exotic food and began what has become my lifelong passion for film.

I remember hearing stories of “tough guy” Jack Kesselman from my older brothers and sister. I also remember after my dad passed, my father’s half-brother Bernie showed us where he, my father and my Uncle Wally were “drug up” in the Bronx, and regaled us with the story of my father “the hero,” who chased down and scared the living daylights out of the tough kids in the neighborhood who stole his religious half-brothers’ yarmulkes during a game of stickball. I, however, rarely saw glimpses of this Jack.

Since I began writing these pieces, I have met men who knew my father, and I have come into contact with relatives on my father’s side who I never knew existed. I have seen photos of my father as a young man that I have never before seen, with friends and relatives he loved, people I never knew. His cousin, Iris (now in her 70s), and her husband recently came over to my sister’s home for dinner: It was the first time our families had met. I asked Iris why my father and she never kept in touch after he moved to California. Iris simply explained, “That was just Jackie’s way.”

A few months earlier, Iris had sent me a letter that my father had written to her after her mother, Bessie Kesselman, the woman he had loved like a mother, passed away. Dated December 2, 1951, it was postmarked from Israel, and when I read the handwritten letter, I cried. The letter was so beautifully composed, so deeply felt, that at first I couldn’t believe it was written by my own father. I never knew Jack Kesselman as a writer. After stepping through some of his footsteps and reading what he wrote, I can only hope that one day I might become half the writer he was.

The author of “Writing in my Father’s Footsteps” , Jonathan Kesselman, is the youngest son of Jack Kesselman. Jack is survived by his daughter Beth, his sons Joshua, David and Jonathan, and his grandson Jacob Cole Kesselman.

Jonathan Kesselman is a screenwriter and film director (“The Hebrew Hammer”), and an adjunct professor at Yale University.

Published in The Jewish Daily Forward in 5 parts from January to June 2009 (www.forward.com). Reproduced with the kind permission of the Editor, Dan Friedman.

The articles in The Jewish Daily Forward include a video of interviews with soldiers who fought for Israel as part of Machal – http://www.forward.com/articles/14985/