Part I: Writing in My Father’s Footsteps

History

By Jonathan Kesselman

This is a story of loyalty and betrayal. It’s a story of bravery and subtlety, of mortal stakes on a global stage. It is also a thrilling story filled with “cloak-and-dagger elements,” featuring storied American men both famous and infamous: Harry Truman, Mickey Marcus, Hank Greenspun, Jimmy Hoffa and Charles Winters (the man who was recently posthumously pardoned by President Bush), just to name a few. It is a story of unknown heroes, as well: Norm Schutzman, Ralph Lowenstein, Si Spiegelman, Paul Kaye. And, as it turns out, it is also a story of my father.

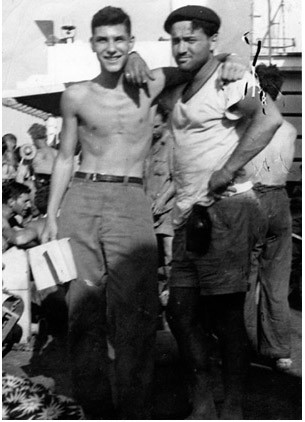

HERE TO HELP: Machalniks arriving in August 1948 on the ship known as the Pan York, aka Kibbutz Galuyot — the ingathering of the exiles.

Films about the Holocaust remind us, while we sit in comfort, of past atrocities. They make us remember a little, and that pebble of discomfort helps them win awards — especially on January 27, International Holocaust Remembrance Day, when survivors and families of both the dying and the dead come together and remember what they can.

Although remembering the Holocaust and reminding others of it is crucial, growing up under the influence of these films can be damaging. Compared with the standard heroism of Westerns and war movies, 20th-century Holocaust films conveyed a mentality of victimhood. As a people, there is clearly no doubt that we have been victims in the past, and yes, sometimes we are still, but that is only one facet of who we are as Jews. Although we are relatively few, we have achieved, and continue to achieve, some of the world’s greatest accomplishments. We always persevere; we always fight.

Personally, I tell stories. Very recently, one of the most incredible stories unexpectedly revealed itself. Even more incredible, it was about my own father. Every story has a beginning, and my story began in Park City, Utah.

My eldest brother, David, an airline pilot, was watching “Saving Private Ryan,” with his son, Cole. It is a film that deals with themes of heroism and selflessness, and as such, it made my 10-year-old nephew recollect the heroic myths he had heard about his own family.

Although his grandfather passed away seven years before he was born, Cole had always been curious about, and somewhat obsessed with, the idea of his Grandpa Jack. I think most children are curious about the relationships their mothers and fathers had with their own parents. We are the products of our families, and so we crave any information that might tell us who we are and, even more important, whom we might become. We also crave a personal connection to what we admire in the world.

As for my father, Cole’s grandfather, I knew that he had, at the age of 17, lied so that he could enlist to fight in World War II. I also knew that he had fought in Israel’s War of Independence. I remember how, when I was a child, my dad had a predilection for biographies and films about war. But one thing he never spoke to any of my family about in any detail was his own biography: his experiences in the two wars he fought. And we never pressed him, as I always assumed that he saw many atrocities and he didn’t want to delve into that part of his life or, at the very least, pass on those unpleasantries to his family. Beyond that, we didn’t know where my father had been and what he had done or seen.

I got a breathless call from my brother in Park City that night. After being grilled by my nephew for more information, my brother had stumbled upon an online document about an organization of soldiers my father belonged to during his time in Israel. It was called Machal.

“That’s not all, Jonny,” my brother said, with a sense of urgency. “Turn to page 10!” And so I did.

There, in a blurry sepia photo, was an image of my father standing at the far left of the back row among a group of soldiers, his name captioned at the bottom. I don’t remember how long I stared at my father’s face. There are only a few pictures I’ve seen of my father as a young man. But there he was, the only man wearing glasses and standing tall at 6 feet 1 inch, staring back at me.

Soon I was getting similar breathless calls from the rest of my siblings. “This is incredible!?” “What and where the heck was this?!” It was at this point that I, being the writer in the family, took it upon myself to find out.

“Machal” is a Hebrew acronym for “Mitnadvay Chutz La’aretz,” translated into English as “Volunteers From Abroad.” In 1948, once the British Mandate was lifted and the State of Israel was declared, about 3,500 Jews (and some non-Jews) from all over the world were recruited by the underground organization the Haganah to protect and defend Israel from the seven Arab nations invading at the time. Of those 3,500, about 1,000 men were from North America. My father was one of them.

Without these men, Israel would not exist.

Last November, 15 years after my father’s death, it was a film about a war, and the curiosity of the 10-year-old grandson Jack Kesselman never met, that set me on a journey to find out what my father had done, where he had been and what he had seen. The story you will read involves 1,000 of the bravest and most selfless North American Jews. It rivals any story of Jewish heroism in this or any other century.

It’s a story not many Jews are aware of, and I’m proud to say that my father was an integral part of it. Although my father never shared his story with me, and many of the people from his company have passed, I have met and spoken with a man who knew my father, a man who led his company, and many other men who were there. Their stories are beyond captivating. I will piece together the stories of others to tell that of my father and of the 1,000 men who sailed from North America to build the Jewish state out of hope and fearlessness.

Part II: Writing in My Father’s Footsteps

From Crotona Park to Tel Aviv: Why He Fought, and How He Got There

Israel’s history underfoot in New York: This Haganah plaque is on the sidewalk of East 60th street in the heart of Manhattan just outside the Rouge Tomate restaurant, formerly Hotel Fourteen where the Haganah was based.

When my father was 9, his mother, Bessie, developed cancer. At the age of 12, my father returned home from school to find all the mirrors in his home covered; Bessie had passed away, and my father was told by his father, Bennie, a fruit salesman, that Bessie had died because my father had been “bad.” Bennie decided he could not care for his son, and for five years my father was passed around from relative to relative.

My father spent a great deal of time with the Spiegels and formed a very close bond, in particular with his aunt Bessie Kesselman, who ironically had the same name as his deceased mother. While fighting in Europe, Aunt Bessie’s son Danny died in a tank battle. This shook my father to the core, and it was then that he decided to enlist to fight in the Second World War; he was 17.

In 1945, my father arrived in Italy: a trained soldier without a battle to fight. From Italy he was transferred to the Pacific and, as luck would have it, missed combat there, as well. Soon he returned to his home in the Crotona Park neighborhood of the Bronx. While he was alive, I never took the opportunity to ask my father how or why he went to fight for Israel: whether out of hope or rage, or just because he was asked. What I did do is ask some of the people who may not have known him but nonetheless walked alongside him.

Norman Shutzman, who was to become my father’s commanding officer in Palestine, had been a soldier in the U.S. Army for four years; he fought in an anti-aircraft unit in the Pacific in 1942, and then retrained to subsequently fight for the infantry in France and Germany. When Shutzman returned home to Wilmington, Del., with the rank of captain, he had seen enough; he was done fighting. He threw away his uniform, his medals and anything that reminded him of the war. Around 1947, however, Shutzman had a life-changing epiphany: A secular Jew who had never been a Zionist, he was galvanized by the thought of what a Jewish state could mean for his people. Suddenly, Shutzman felt that if he did not go and help, he would not be able to live with himself. When he told his parents of his plans to go back to war, they pleaded with him to stay. In fact, the day he left home, his father refused to say goodbye to him.

Not knowing whom to contact, Shutzman reached out to the Jewish federation in Delaware, which encouraged him to travel to New York to obtain more information. It was there that he encountered the Haganah, the Jewish underground group responsible for the illegal smuggling of North American soldiers and armaments into Israel.

Si Spiegelman is the former head of the American Veterans of Israel, an organization formed in 1963 with a stated mission: “To preserve and strengthen a spirit of comradeship among its members; to assist worthy comrades; to perpetuate the memory of our dead and to maintain and extend the institutions of freedom, and to foster good will between the United States of America and Israel.” He did not know Shutzman at the time, but he had reasons of his own for volunteering. Born in Belgium, his family escaped Nazi occupation when he was 12. As the family was fleeing, he recalled his father kicking a member of the Gestapo, who was attempting to arrest the Spiegelmans, off a trolley. The family eventually managed to escape Antwerp through France and Spain, and from Spain Si traveled to Cuba on a cattle freighter. In 1946, his family finally found the way to the United States. Finally “home,” the 16-year-old Si, filled with rage from his family’s ordeal, became active in a Zionist youth movement, and through this organization he eventually began to volunteer for the Haganah.

Though Spiegelman did not know Paul Kaye (Kaminetsky), who in later years came to be one of his closest and oldest friends, Kaye had begun to volunteer for the Haganah around the same time. A native New Yorker, Kaye enlisted in the Army to fight in Second World War upon graduating from Chelsea High School in Manhattan. After finishing boot camp, he became a marine engineer and, as he awaited his first action on a Pacific-bound flotilla, the atomic bomb was dropped and his ship was turned around. Back in the United States, Kaye was demobilized and found himself working in a record shop in New York. One day, he received a strange phone call:

“Paul Kaminetsky, would you like to help your people? We know you’re a marine engineer. If you do want to help your people, be on the corner of 29th and Lexington Avenue, Southeast Corner, 4 p.m., on Thursday. A man in a black leather jacket will be there with a newspaper under his arm. If he puts the newspaper under his arm, follow him. If he puts it into a wastebasket, please leave quickly. It means you’re being followed.” There was a click on the other end of the line as the phone went dead. Kaye was intrigued.

The recruitment of North American soldiers was centered in New York City. An organization known as Land and Labor for Palestine was the legitimate front. Land and Labor sent supplies to Israel very carefully; however, the organization was not allowed to send arms. Most potential recruits and, most likely, my father furtively met with operatives from Land and Labor in Manhattan at the Hotel Martinique, with a run-down French Décor, near 34th Street and Broadway.

After potential recruits were interviewed, they were taken to meet Teddy Kollek, head of the Haganah. Kollek based the Haganah out of Hotel Fourteen, on East 60th Street. The hotel was upstairs from the world-famous Copacabana, where Frank Sinatra, Lena Horne, Jackie Gleason and many other stars of the day performed. As one Machalnik, who requested not to be named, remembered: “For approval to make sure you weren’t infiltrating, you had to see Teddy. I always wondered if Teddy was tired out from all of the showgirls when he saw you, because he was always lying down when you’d meet him. Anyway, you’d come in and he’d look you over, and that was it.”

Kollek later went on to become Jerusalem’s mayor for 40 years, and one of its greatest fundraisers. To this day, outside the Copacabana there is a plaque that reads, “This building sheltered the clandestine mission of the ‘Haganah,’ Israel’s pre-state defense forces, which labored unceasingly for Israel’s independence and survival.”

Danny Greenspun, son of Hank Greenspun, who eventually started the Las Vegas Sun, recalls one story his father told him about Kollek and the Copa. Downstairs, Sinatra would perform at the club, while upstairs, Kollek was running the Haganah. Kollek was having difficulty bribing a captain of a ship filled with arms that needed to be smuggled into Palestine. He ultimately confessed to Sinatra what he was up to, so Sinatra decided to lend a hand and personally delivered the bribe money to the captain. Awed that Sinatra was asking him for help, the captain took the bribe, and the ship set sail for Palestine.

At the time, Arabs were allowed to bring arms into Palestine; Jews were not. Kollek enlisted Hank Greenspun and Al Schwimmer, a former U.S. Army Air Force flight engineer, to smuggle arms into Palestine for the Jews. Greenspun, a well-connected Jew in Vegas, enlisted the help of the Purple Gang and such mobsters as Meyer Lansky, Bugsy Siegel and Lucky Luciano. Jimmy Hoffa was also a supporter. People on the street knew it was union practice to drop shipments in a scheme to collect hazard pay, and Hoffa made sure that the teamsters knew never to drop any of the shipments (invariably filled with ammo and arms) bound for Israel.

In July 1950, Greenspun and Schwimmer were convicted of violating the U.S. Neutrality Act, an arms and personnel embargo to the Middle East. The men were fined $10,000, but never saw any jail time. After talking to Kaye and Spiegelman I came to believe that maybe if Greenspun and Schwimmer had not taken the rap, other North American Machalniks would have been arrested when they were home from Israel. In October 1961, President Kennedy pardoned Greenspun, and to this day, there is a park in Jerusalem named after him. In 2000, President Clinton pardoned Schwimmer. and just this past December, President Bush posthumously pardoned Charles Winters, a non-Jewish Englishman who spent 18 months in prison for delivering B-17 bombers to help in the fight.

The Haganah provided most members of Machal, including Kaye and my father, with falsified documents that would allow them to enter Israel. Kaye was reborn a South African with the last name Kaplan. Another Machalnik metamorphosed into David Kampinksy, a carpenter from Bucharest. Schutzman sold his bowling alley, and overnight he became the star flexible joint salesman for Zallea Brothers, one of the largest flexible joint manufacturers in the country.

And in the summer of 1948, my father, whose new name I do not know, held in his hand a brand-new passport as he boarded a decommissioned American warship as a Belgian-lace salesman bound for Marseilles.

Part III: Writing in My Father’s Footsteps

The Pan York and Aliyah Bet: The Men and the Ships That Beat Bevin

My father arrived in Marseilles in late July 1948, as a lace salesman from Belgium. Gloria Kessler, a nurse working at a hospital in Chicago, had decided to give up her career to smuggle herself into Palestine to help. She, too, received falsified documents from Teddy Kollek at the Hotel Fourteen and remembers sailing with my father to Marseilles from New York. Once they arrived in France, my father met three more American volunteers: Frank Perlman, Jack Shulman and Ralph Lowenstein.

Courtesy of Frank Perlman

Young, American and About to Save Israel: Aboard the Pan York, early August 1948, shipmates of Jack Kesselman — Ralph Lowenstein, 18 (left), of Danville, Va., and Frank Perlman, 27, of Pittsburgh.

Lowenstein I knew originally from the only photograph I had of my father from this period, and he was the first person I tracked down. Today, he is dean emeritus of the College of Journalism and Communications at the University of Florida, heads the American Veterans of Israel in Florida and helped to build the only museum in the world dedicated to Machal. He has also written a book about his time in the war, “Bring My Sons From Far: A Novel of the Israeli War,” later republished in paperback as “A Time of War.”

Upon arrival in Marseilles, my father, Lowenstein, Kessler and the rest of the American volunteers slept in a camp alongside Holocaust survivors: The displaced persons, newly rescued from the camps, still lived in a state of heightened anxiety and fear. They were yet to feel “free.” Lowenstein recalls that since these men and women had just escaped the nightmare of the camps, where they were forced to “live like animals,” a fight would invariably break out every time food was rationed out. The DPs (Displaced Persons) afraid that every meal might be their last, would hide bread under their mattresses.

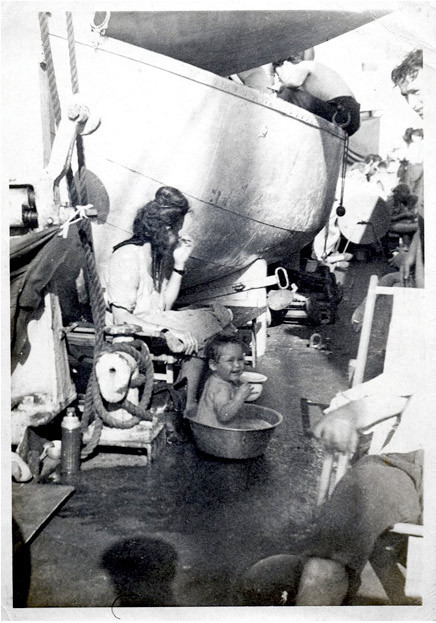

After three weeks in Marseilles, during the second week of August 1948, my father, Lowenstein, Kessler and the 25 American Machalniks boarded the Pan York, a dilapidated Panamanian boat originally built to ship bananas. For carrying passengers, the ship was rebuilt with three floors in each of its three holds.

On the Pan York’s first voyage from Bulgaria, it carried 7,500 people. On that voyage, the ship was captured by the British. The passengers were interned in a camp in Cyprus until Israeli independence was declared on May 15.

Paul Kaye, whom I wrote about in the last installment, was a crew member of another Aliyah Bet ship, the Hatikvah. He also experienced capture and internment in Cyprus; however, Kaye eventually escaped, along with the crew of the Hatikvah, and continued his mission. The incredible story of his escape is featured in the documentary “Waves of Freedom,” which the Forward and the JCC in Manhattan will be screening in May. Kaye recalls the first time his crew picked up DPs. Coming onto the ship, each survivor hugged him and thanked him in Yiddish. He recollects the profound feeling that he was rescuing not just victims, but also family members whom he had lost in the camps.

My father sailed on the Pan York during its second voyage, its first having taken place after Israel’s War of Independence had begun. On my father’s voyage on the Pan York, there were about 2,800 people on board. On each of three floors of the Pan York, wooden shelves 5 1/2 feet deep and three tiers high were constructed to carry the human cargo.

This meant that typically, each passenger had a shelf space 20 inches wide and 5 feet deep; there were no pillows or mattresses. As my father was 6 foot 1, more than half a foot of him stuck out over the edge of his shelf when he would lie down to sleep. During the five-day trip to Palestine, there was no fresh water; my father was rationed one glass of water a day. Lowenstein recalls the experience:

Food consisted of cheese and crackers for breakfast, broth and crackers for lunch, sardines and crackers for dinner. There were no toilets with running water for the 2,800 passengers, just 10-hole outhouses. The five days on the Pan York were the most miserable of my entire life. Yet, for the Holocaust survivors, it was not that bad. They had seen the same and worse — for years, often without food.

The Pan York was one of the many boats involved in what was known as Mossad l’Aliyah Bet (Aliyah Bet for short), a network of ships from around the world whose purpose during the British Mandate for Palestine, which lasted until May 1948, was to smuggle more than the sanctioned 1,500 Holocaust survivors into Palestine per month. On these ships, alongside the DPs, Machalniks like my father were also being smuggled in to defend Israel. The ambition of Aliyah Bet was to break the back of the British blockade. At the time, hundreds of ships were carrying DPs toward Palestine. Most were European, with only 10 ships (plus three or four smaller boats) sailing from the United States.

Machalniks were not just smuggling themselves and others past the coastguard; they were facing off with the pre-eminent global naval power — Great Britain. In control of its mandate, Britain had seemingly promised a Jewish state in the Balfour Declaration of 1917. But the MacDonald White Paper of 1939 — created to placate the oil-rich Arabs — seemed to countermand that agreement. David Ben-Gurion, in response, declared, “We will fight the war as if there were no white paper and fight the white paper as if there were no war.”

Aliyah Bet was part of Ben-Gurion’s fight. On the face of it, Aliyah Bet was intended to keep the world spotlight on the need for a Jewish state. But British actions convinced Machalniks and others that regardless of the mandate, the British government was setting up Israel to fail as a nation. At the time, the British were allowing in only 1,500 DPs each month and constructing naval blockades, all the while allowing the surrounding Arab nations to enter and attack, including the Transjordan army, which was even trained and equipped by the British.

Most of the men I interviewed believed they were fighting for Israel’s very survival and that their actions had more profound strategic implications. One Machalnik, who wishes to remain unnamed, told me of Jon Kimche’s contemporary political analysis. Kimche argued that carrying DPs to Palestine from Europe served a more important purpose than mere publicity. Ernest Bevin, the British foreign minister, had acted to effect the Morrison-Grady Plan between 1945 and 1947. This plan, agreed upon by the British and the Americans, called for a single sovereign state with British military control and Arab sovereignty, in which there would be a number of cantons, including a Jewish canton.

According to Kimche, Bevin had calculated that there were about 200,000 Jews capable of military action in Palestine and that 100,000 British soldiers could control and manage any Jewish uprising. Bevin thus took great pains to block any further Jewish immigration. He turned back ships carrying DPs and facilitated the deportation of the passengers back to Cyprus, Eritrea or even Europe.

Eventually, however, the number of ships carrying DPs, among them the Pan York and the Hatikvah, overwhelmed the capacity of the Cyprus and Eritrea internment camps and ultimately broke the will of the British. Bevin eventually gave up on the Morrison-Grady plan and agreed to abide by the recommendations of the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine. Aliyah Bet, in essence, broke the Allied will to resist the emerging alternative of the partition of Palestine, which included a Jewish state in control of Jewish immigration. The men of Aliyah Bet forced Bevin to honor Balfour’s promise.

The Pan York, with my father aboard, docked in Haifa on August 14, 1948. When the ship reached port, most of the American volunteers did not speak Yiddish fluently enough to get past the U.N.’s inspectors. Lowenstein recalls that my father and the other American volunteers had to jump down to a tugboat on the starboard side of the ship in order to be smuggled into the country. The tugboat sailed to another secure dock, and my father was taken by bus to a kibbutz so that he could clean up and eat. From there, he and Lowenstein were driven directly to a DP camp in Tel Aviv called Tel Letvinsky. At the time, Tel Letvinsky was a former British army base; today it is the site of Tel Hashomer, an Israeli hospital.

My father and Ralph spent five days at Tel Letvinsky before they parted ways and journeyed to different units, never to see each other again. Before they left, they took a picture together with some other volunteers; it was that same sepia photo that my brother and nephew found by chance, and the same photo that started this journey for me. Ralph remembers the photograph being taken by an older man using a camera with no shutter. In order to capture the image, the man removed the lens cap for a second or so and then replaced it. In the photo, all the men are smiling. I can only imagine what was going through my father’s mind. He was 22 and had never seen a day of combat, but he was in Palestine illegally, ready to fight and risk his life for an idea: a Jewish state were Jews could live free from persecution.