Michael Flanagan was born in May 1926 in the UK, and completed his education at a technical boarding school. Although he was under-age, in 1942 he was accepted into the 47th Dragoon Guards Regiment at the age of 16.

Michael Flanagan was born in May 1926 in the UK, and completed his education at a technical boarding school. Although he was under-age, in 1942 he was accepted into the 47th Dragoon Guards Regiment at the age of 16.

He participated in the Allied invasion of Nazi-occupied France on 6th June 1944, landing at Normandy shortly after the infantry. His unit was involved in the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. He later served with the occupation army in Berlin.

He was then posted with his regiment to India, Syria, and finally to mandated Palestine. After the British left on 15th May 1948, following the declaration of the new Jewish State, Mike remained with the small British garrison which stayed on to load the heavy equipment onto the waiting ships in the Haifa Bay. This group still controlled the enclave which included the Haifa docks and airport.

During this period, Mike and a fellow sergeant, Harry MacDonald, often frequented a small café in Haifa. They often discussed their return to Britain, not completely happy with the idea of returning to what was then a class-conscious society. Both had ideas of emigrating to one of the British dominions, hoping to find better opportunities there.

One evening they parked their truckload of jerry cans full of petrol outside this café in Haifa. They had been ordered to destroy the jerry cans in line with the official British evacuation policy of keeping items of military value out of Jewish or Arab hands.

While discussing how to complete this task, they were overhead by a short ginger-haired Jewish man sitting at a nearby table, who then approached them and said, “Why destroy them? I’ll buy the whole lot from you.”

“No-one said we couldn’t,” commented Flanagan. “Why not?” said, “it would save us a lot of trouble.”

Deciding quickly, Flanagan gave the key to the truck to the stranger. “Take the whole lot and Mazal Tov.” This was not an uncommon practice, as some British soldiers found the Haganah a most lucrative market for equipment taken from military warehouses. Others were more interested in helping the Jewish cause than making money for themselves.

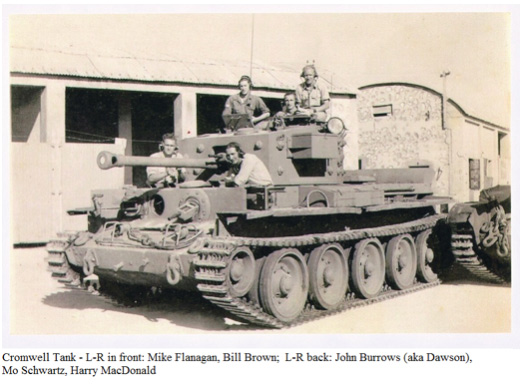

From this sale of the petrol, they eventually got involved in removing four heavy Cromwell tanks from their camp, which were assigned to protect and guard the Haifa Airport.

Flanagan and MacDonald were amongst the minority of Mandate soldiers who favored the Jewish cause. Flanagan even saw the Jews fighting the same British army his people had fought so bitterly in their own underground. But stealing tanks would certainly incur a long prison sentence if they were caught, unless they deserted.

With assurances from Dov, the Haganah agent, that they would be well provided for by the Israel authorities – 3,000 pounds sterling to each man, as well as new identities and a new life in Israel, if they chose to remain. That finally persuaded both men to go along with the scheme.

The initial plan called for taking all the four Cromwell tanks in their care. The Haganah provided two truck drivers who would be taught the basics of handling a tank by way of sketches and theory.

Using their rank, Mike and Harry volunteered to take over the midnight guard at the camp. At the correct time, Flanagan crawled into the first tank, MacDonald into the second, with the two Haganah men in the third and fourth tanks.

Flanagan closed his eyes for a moment to shut out the thought of what awaited them if the plot failed. He would have no time to check if the other tanks were following. He groaned quietly.

With a deafening roar his tank started up successfully. It skidded forward and lurched towards a seldom used and locked side gate leading to the Haifa Bay area. Within minutes the tank had smashed through this gate, which landed on MacDonald’s tank some 20 yards behind. Both tanks slithered down a side road to a rendezvous with three waiting jeeps. One of them flashed a signal and the tanks followed for about five miles to a spot where two large transporters were to take them to the old Tel Aviv exhibition grounds at the end of Ben Yehuda Street.

A Haganah man came up to them and told them that the transporters would not be coming. They would have to drive the tanks all the way. Only then did they realize that the third and fourth tanks were not with them. Both the Haganah drivers had not succeeded in getting the third and fourth tanks out of the camp, but they did manage to slip away and reach safety. Two Cromwells were better than none!

On arrival in Tel Aviv the two sergeants were taken to the Eden Hotel in Ramat Gan, where Canadian Machalnik Lionel Druker was sent to fetch and recruit them into the newly-formed 82nd Tank battalion’s “B” Company. Druker had already found three other British soldiers who had joined the cause of the new Jewish State at Tel Litwinsky – Desmond Rutledge, Johnny Dawson (aka Burrows) and Bill Brown.

The two Cromwells joined a single Sherman acquired by bribery. The Sherman was initially without its 75mm cannon and only armed with two heavy machine guns. Also recruited at Tel Litwinsky was Dan Samuel, who had been the youngest tank major in the British Army and was also a grandson of Lord Herbert Samuel, the first High Commissioner for Mandated Palestine. Other English-speaking volunteers were also recruited at Tel Litwinsky, some already experienced and others to be trained by Samuel, Druker, Flanagan, and MacDonald.

An “A” Company was also formed with 10 light two-man French Hodgekiss tanks, manned by Russian and East European refugees who had served as tank crewmen in the Red Army.

Lionel Druker was the first commander of the ‘B” heavy tank company. Later Druker was transferred to command a new Armored School. South African Clive Selby took over, and later, when Selby returned to South Africa, Druker returned to take command. Again, Druker in his personal story records the training of a fellow Canadian, Mo Swartz, to handle the early Sherman.

Their first action was the capture of Lod (Lydda) Airport from the Jordanians during the July Dani Operation. After that, in the last attempt to take Latrun, the tanks were sent to Quala near Ramallah to prevent a Jordanian counter-attack. At the same time they had captured a number of Arab villages which had opened the road by-passing Latrun. Lod then became the 82nd Battalion’s base.

During this action, one Cromwell had actually succeeded in entering the Latrun Fortress under the command of another British deserter known as “Tex.” His tank fire had caused the small Jordanian garrison to start withdrawing. On ordering his gunner to fire another shell, the gunner responded that the shell casing had jammed. The only casing extractor was with Rutledge in the other Cromwell at Lod. He had no alternative but to drive there and get it. His tank was useless without the use of an operable cannon. Behind him had been an entire convoy of Palmach Yiftach infantry. He drove his tank to the leading truck and shouted in English to instruct the convoy to simply drive into the unoccupied fortress. On reaching Lod, he found the entire convoy behind him. The Palmach driver of the first truck had misunderstood the English and simply followed him. Bad luck thus prevented the IDF from entering and occupying Latrun with no further losses.

In Operation Yoav on 16th October, Flanagan experienced his most difficult time during the failed attack on the Iraq-el-Manshiya fortress. They were to support infantry units of Palmach Hanegev Brigade. Flanagan drove the lead Cromwell under the command of MacDonald, followed by Rutledge in the second.

As he pressed hard on the accelerator, Flanagan experienced a strong excitement such as he had never experienced when fighting with the British Army in World War II. This country represented for him a tremendous challenge, as did his desire to save it. He felt that he was fighting for something personal, something of his own, and if he lived through this, he would convert to Judaism and marry his Jewish sweetheart Ruth, and settle on a kibbutz where he would pick cotton and raise cattle. This seemed the right place for a bored Irish motor mechanic who would rather repair tractors than cars.

Rutledge’s tank had lumbered on as he tried to keep up with Flanagan and MacDonald in the leading Cromwell. Suddenly the vehicle ground to a halt with its gearbox jammed. They were stuck in hell. Flanagan raced ahead, oblivious of what was happening around him, having lost touch with the infantry. The heavy Egyptian shellfire had even kept MacDonald from looking out of the turret to observe events around them, and he assumed the other armor and infantry were following.

A shell suddenly exploded directly in front of the tank which came to an abrupt halt. Flanagan had been hit by shrapnel which entered the tank through the small front window and struck him in the chest and head. The co-driver next to him shouted through the intercom to MacDonald in the turret, “Drivers hit, drivers hit.” He managed to stop the bleeding, and bandaged Flanagan’s wounds. Flanagan then started the tank up again and kept advancing. MacDonald asked him if he could keep going as the Czech co-driver had very little experience in handling a Cromwell. “Yes, okay,” he answered as he approached the Police Fortress. MacDonald shouted back, “Then ram through the barbed wire.” Once inside, Flanagan was aware that small arms fire was hitting their tank, but he knew that it was ineffective against the tank’s armor. “Mac,” he yelled, “take a look and see where the others are.” MacDonald cautiously lifted his head out of the turret and realized that they were alone. He then shouted, “Let’s get out of here.”

Flanagan turned the tank around while Egyptian fire kept bouncing off the armor. Less than a mile to the rear, the second Cromwell remained crippled and slightly further back, a Hotchkiss rested on its side in an anti-tank ditch. Rutledge, whose tank was besieged by infantrymen seeking cover, climbed out and ran to meet Flanagan’s retreating Cromwell, which managed to tow the other one to safety, even though the barrel of its cannon had split open, keeping the enemy at bay. They reached the safety of Kibbutz Gat where Rutledge’s wife Miriam was waiting for them.

A third of the attacking infantry unit had been killed or wounded. Half of the Hodgekiss tanks had been hit, and lay crippled. South African medic Hymie Goldblatt had much to do treating all the wounded.

Later, on 21st October, the 82nd provided support to the troops capturing Beersheba. By that time “B” Company had been reinforced with a number of half-tracks and home-made armored cars. One of the half-tracks had been fitted with a six-pounder anti-tank cannon. Both Cromwells were out of action at the time and as a substitute this half-track, named the “Beersheva Tank,” led the spearhead of the French Commando company under the command of a non-Jewish French officer Thadée Difre (aka Teddy Eytan) into the town. Three South Africans were in the crew of six – Morrie Egdes (gun loader), Eddy Magid (gunner) and Stanley Behr (driver).ᶦ They were ordered to shell the British-built police fortress which was still holding out.

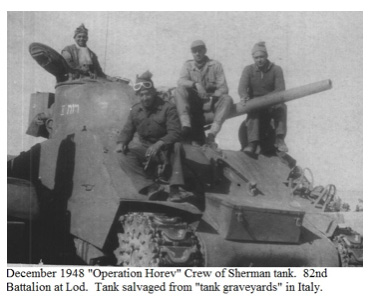

By the time Operation Horev began on 22nd December, “B” Company had acquired a few more Sherman tanks. Moving across an old Roman road prepared while other forces made diversionary attacks, the 8th Brigade, which included the tanks, successfully captured Auja-el-Hafir (today Nitzana). Later, on 7th January, whilst the tanks were moving on Rafah, RAF patrols flew over the Israeli lines. Five RAF fighter planes were shot down, four by 101 Squadron and one by British deserter Johnny Dawson (Burrows) firing his tank’s heavy machine gun mounted on the turret. The pilot succeeded in bailing out, and was taken prisoner by the Israelis.

Dan Samuel recalls a number of other volunteers; British Norman Levy, who later became a member of the British Columbia Parliament; Frenchman Arthur Feldman; Mario Gurewitch, a very emotional lawyer from Chile; Abe Goldberg, who had served in World War II in the British Armored Corps and had previously fought in the Spanish Civil War. One of the Czech volunteers, Michael (Ben Zvi) Zwilling, recorded that eight British Army deserters had served in the 82nd Tanks. They were part of some 20 deserters who had joined the Israeli cause. 15 names are known – one of them, Raymond Dodge, fighting in the Palmach Hanegev Brigade, was killed in the difficult early battles on the Ashdod sand dunes on 3rd June 1948.

Anecdotes:

1. Dan Samuel had attended Flanagan’s wedding in a Tel Aviv café. MacDonald served as best man. The religious authorities were late, and finally a seriously exasperated Flanagan, turning to MacDonald, came out with the memorable phase, “Jesus Christ, Mac, where’s the Rabbi?”

2. The tanks stolen by Flanagan and MacDonald were supposed to be part of the last equipment to be loaded onto the waiting ships. The angered British General Cunningham commanded the last troops to embark in order not to delay the departure. He had been invited to tea with the Mayor of Haifa, which he refused. The next day the “Palestine Post” headline read “No tanks, no tea.”

Having settled down in Israel with his wife Ruth, Flanagan served as a reservist in the 1956 Sinai Campaign, the 1967 Six-Day War, as well as the Yom Kippur War in 1973. He and Ruth had two children, Dani and Kareen.

For a short while he worked as a mechanic for the Dan Bus Company, and after that as a civilian worker for the IDF, repairing heavy vehicles at their large Julis Camp in the Haifa Bay area. Together with a fellow worker, Amnon Domani, at Julis, the couple became members of Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’Emekim, and Flanagan worked in the garage and with the field crops. He had also studied agronomy at the Faculty of Agriculture in Rehovot, after which he had been sent as an emissary to Africa for a number of years.

Later, following the death of his wife, and using an Israeli passport in the name of Peled, he visited Ireland and Canada. In Toronto he met the widow of his 82nd Canadian comrade Mo Swartz, Shirley, whom he later married, living with her until his death on 31st January 2014. His body was flown by his new family (Shirley and stepchildren) to Israel from Toronto, and he was buried alongside his first wife Ruth at the Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’Emekim cemetery.

He is survived by his son, daughter, four grandchildren and five great-grandchildren In Israel. In Canada he is survived by his second wife Shirley, as well as three step-children and four grandchildren.

Author: Joe Woolf, Machal Chief Researcher

Sources:

(i) The eulogy by his grandson Lior Herzl.

(ii) “South Africa’s 800” by Henry Katzew, 2003

(iii) “The Secret Army” by Prof. David Bercusson, 1983.

(iv) “Genesis 1948” by Dan Kurzman, 1970.

(v) “The Arab-Israeli Wars” by Chaim Herzog, 1982.

(vi) Personal story of Dan Samuel – World Machal website.

(vii) Personal story of Lionel Druker – World Machal website

ᶦTwo of these three South Africans became mayors in the 1980s – Egdes of the town of Sandton, and Magid of nearbyJohannesburg.